Request accessible format of this publication.

9. The House the Lotteries Built

Author: Minna Muhlen-Schulte

Hear directly from the author

The saga of constructing the Opera House, its heroes and villains loom as large in our imagination as the modernist icon itself on the Harbour today.

From the seed of the idea planted by Sir Eugene Goossens to Jørn Utzon’s spurned creative genius, to the role of Minister for Public Works Davis Hughes and the triumph and tragedy of Australian architect Peter Hall, it’s remarkable it succeeded at all.

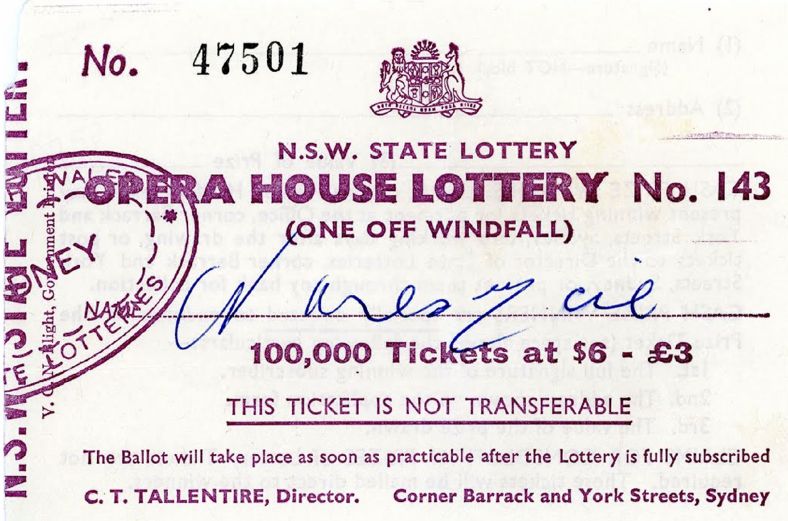

Backstage throughout was the less glamourous role of NSW Treasury. It controlled the ‘Sydney Opera House Management Account’, created as part of the Opera House Act 1960 to hold funds from the Opera House Lottery. Tapping into the tried-and-true blue Australian tradition of gambling, it was ultimately the people who funded the Opera House from their own pockets. A total of 496 lotteries and 86.7 million tickets raised $102 million between 1957 and 1986. Without these lotteries, the Opera House would never have been built.

However, before the Dane’s vision took centre stage on the peninsula, the site of the Opera House was known as Tubowgule. It was here one of the first houses in the colony was built for Aboriginal man Bennelong, the eponymous hero of the peninsula. It was here that shells were crushed and burnt to make lime mortar to bind the bricks of the colony. Later hundreds of migrants would help engineer and build the Opera House by hand, while many others across Australia would gamble on the lottery hoping to win to build or buy a house of their own. The site carries its own specific material timeline, where hands have moulded shells, mortar, clay and created enduring myths and memories of this site.

The First House

Aboriginal people have occupied Sydney from at least 38,000 years ago. Over hundreds of generations, they bore witness to the creation of the Sydney Harbour landscape as we know it today. Tubowgule was at the end of a ridge, surrounded by rocky shoals that disappeared underwater with the high tide. Before it was Tubowgule, it was a speck in a series of deep sandstone valleys threaded with rivers running twenty kilometres further east of the current shoreline. Global warming 18,000 years melted glaciers causing a rapid rise in the sea, which flooded the valleys forming the headlands, points and bays of Port Jackson; ‘only 8,500 years ago the water was 15 metres below its present level. When the sea rise stopped 2,500 years later, schools of tailor and jewfish could swim where parrots and cuckoos may once have flown.’1 To the Aboriginal people of Sydney this rapid environmental change was articulated through creation stories of the ancestral eel being Parra Doowee2 and to other coastal groups, Burirburi the Humpback whale being who shaped this part of Country.3

After the arrival of the First Fleet in 1788, the British colonised the peninsula, naming it Cattle Point and then Limeburner’s Point. Here, shells harvested from Port Jackson and Aboriginal middens were crushed and burnt in kilns to create lime mortar to fuel the colony’s construction, including the first Government House.4 The scale and meaning of these middens have become mythic and even apocryphal in the imaginations of writers. In 2000, architect Peter Myers claimed the middens were piled so high that they formed a proto-monument on the Peninsula:

There is no evidence for Myers’ claim. Instead, Governor Arthur Phillip’s offering to this site was more prosaic but also profoundly personal.

After Phillip kidnapped Aboriginal man Woollarawarre Bennelong – and Bennelong’s subsequent escape from Government House – a complex friendship developed between them. At Bennelong’s request and under Phillip’s orders, ‘a hut was built of brick, 12 feet square and roofed with tiles. Bennelong chose the site and took possession of it about the middle of 1790.'6

Recently, Aboriginal artist Archie Moore reimagined the house and interpreted the gesture from Phillip as an ‘uncommon act of benevolence in Australia’s early colonial history… an act of either recognition and respect, or of imperial enclosure.’7 It seems Bennelong preferred to sleep at Government House, and that the hut became more of a symbol of his status but also an important place for social gathering.

In March 1791, British naval officer and cartographer William Bradley recorded the first performance documented by colonists at Tubowgule, presaging its future 20th century use:

After Bennelong’s return from England in 1795, the hut had been demolished and bricks repurposed elsewhere. Bennelong died at Kissing Point in 1813, and four years later, another man’s vision for the peninsula was unfolding as British architect and transported convict Francis Greenway who as the colony’s first architect designed Governor Macquarie’s Fort. The tidal area between the island and mainland was filled in. In 1903, the fort was toppled for the ‘car house’ or tram depot which in turn was demolished for the laying of the foundations of the Sydney Opera House in 1959.

However, Aboriginal connections to the site did not cease. Although a masculine imprimatur dominates this site’s history, there are women’s stories here too. During the 1880s, Aboriginal women at the Circular Quay Boatsheds had developed a practice of making shellwork to be sold as souvenirs. The practice was influenced by Victorian English handicraft and also missionaries from the South Pacific who sought to foster it as a source of economic independence for Aboriginal women.9

In recent years Aboriginal women’s connections to the site have been interpreted through contemporary artworks that resonate with the long history of shells on this site. In 2002, the late La Perouse artist Esme Timbery (1931–2023) created a whole Opera House from shellwork – a craft inherited from her forebear Queen Emma Timbery (c1842–1916). Emma Timbery’s exact connection to the Boathouse women is unknown, but shellwork as an Aboriginal women’s practice at La Perouse took on a life of its own. Today, inside the Opera House as you look back towards the Tarpeian lawn, you see a new shell monument Bara by Judy Watson, a monument to the Eora women’s bara (or fishhooks) that were carved from shells and dangled from their nowie canoes as they glided across Sydney’s waters.

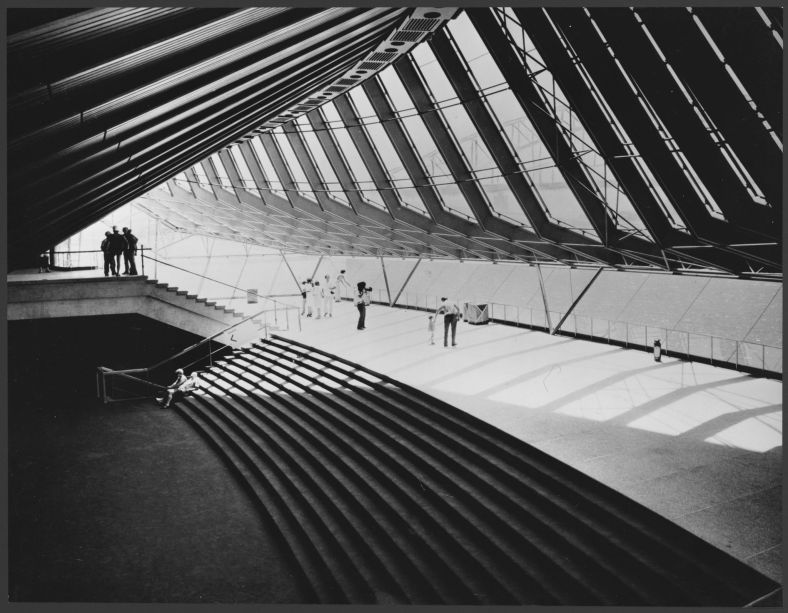

Utzon cannot have known any of this history when he channelled his vision of the site into glimmering vaulted shells of his own. But all the elements of shell, clay, stone, water and light resonate with the material timeline so eternal here. When Utzon and Arup & Partners needed to express the roof mathematically they experimented with parabolic and ellipsoid shapes until they hit upon spherical solutions to derive a final form of the shells. The shells’ custom ‘Sydney Tile’ was made with clay and crushed stone, specifically selected by Utzon so that ‘such a large, white sculpture in the harbour setting catches and mirrors the sky with all its varied lights dawn to dusk, day to day, throughout the year.’10 Many workers hands moulded the tiles in a factory set up under the Monumental Steps onsite, just as the lime burners had worked here over a century before. In 1973, as part of the opening ceremony Aboriginal actor Ben Blakeney was commissioned to play Bennelong. Blakeney delivered an oration at the topmost peak of the tallest shell, calling up the memory of the first house and its occupant:

The House that Joe built

Labor Premier Joseph Cahill was the political founding father of the Opera House. Although it is the brutal scar of an expressway that bears his name, a more fitting moniker for the Opera House was the ‘Taj Cahill’ as testament to his passion for the project from its earliest inception.

Following the 1956 design competition where Jørn Utzon was selected from 220 designs, the battle began for Cahill to win the wrangle the funds and maintain the political and moral high ground. Members within the Labor caucus were the first to attack. The member for Monaro, J. W. Seiffert, made the clarion call against cultural elitism, a theme that would dog the project and its advocates the whole way through its construction. Seiffert claimed the House was preferencing a ‘super class of people.’13

Of all the people that could be accused of an elitist agenda, Cahill was not one of them. Formerly a railway fitter, trade unionist and official ‘agitator’ during the 1917 Great Strike, Cahill took up the cause to promote the need for a world class cultural institution despite the fact he had never seen an opera in his life, ‘he recognised his city was changing… post-war European migrants were demanding a different kind of culture than the one that could be found in the pubs and at the racetrack.’14

The bigger battle was procuring funds in a politically expedient way. Cahill feared the tight vote in the Labor caucus (24 to 17) in favour of the construction of the Opera House and an appeal for funds could still lead to a split in the party. Compounding his fear was a housing shortage where many felt houses should be built not a opera house.15 The Member for Collaroy, Robert Askin – who, 17 years later, would reap Cahill’s glory and cut the ribbon on the Opera House – attacked on both counts of housing and cultural elitism:

Cahill was quick to retort the fowlhouses of Brookvale were in Askin’s own electorate and merely a poor reflection on him.17 With his own party onside Cahill conducted the first appeal at Sydney Town Hall raising 235,000 pounds in just over half an hour, including a ‘kissing party’ trading kisses for cash where Utzon paid 100 pounds to kiss Julia Ricci, the wife of American violinist Ruggiero Ricci.

The appeal was followed by the much-anticipated Opera House Lottery, the biggest lottery ever held in the State, with a 100,000-pound first prize and 50,000 and 25,000 pounds for second and third place. Cahill hoped this would assure critics that funds would not be taken from public works or other commitments.

However, the opposition couldn’t resist. In 1956, Cahill had legalised poker machines in New South Wales; Liberal Party MLC, Richard Thompson was keen to highlight the dissonance between this act and the high culture of the Opera House project:

Member for Manly Evelyn Douglas Darby took issue with the Lottery’s advertisement declaring ‘by investing in this Lottery you will be making a positive contribution to the advancement of cultural development in New South Wales.’ Darby declared that even the NSW Treasurer would be tarnished with this legacy:

Hypocrisy and hyperbole aside, the fact was that NSW Treasury had conducted the Lotteries since as early as 1931, having been instituted to support the State’s hospital system.20 (As discussed in the introduction, Treasury’s uneasy relationship with the gaming industry has remained a point of contention well into the 21st century.) Cahill’s introduction of the special lotteries wasn’t a new idea, but it did ensure the Opera House’s future. In 1959, he charged ahead and signed the 1,397,878-pound contract for the first stage of work.

The contract was signed on the second floor of the Treasury building in a ‘Queen Anne-style-room… heavily moulded plaster ceilings and a marble chimney open fireplace… a dramatically different aesthetic from the building he was agreeing to commence work on.’21 On 2 March 1959, the sod turning at Bennelong Point commenced as Cahill kissed the foundation plaque; while the blast of a police siren set six jackhammers and a bulldozer into action. Cahill said, ‘I’ve watched brick by brick being taken from the old tram shed that was here, and I’m going to watch brick by brick of the Opera House go up.’22 But only seven months later he died after becoming ill at a caucus meeting at Parliament House. Just before receiving a final blood transfusion, Cahill summoned Minister for Public Works Norm Ryan to his death bed and ‘made him promise not to let the Opera House fail. “Take care of my baby”, he joked.’23

The Sydney Opera House Act 1961 was passed the following year by the NSW Legislative Assembly, with the formal provision that Treasury’s Opera House Account would manage proceeds of the lottery and Treasurer’s role advance payments towards the construction costs.

Absurdly, the State Treasurer was empowered as keeper of a spare set of lottery marbles, secured and locked in safe in his office, and a spare lottery ladle in case of breakage.24 The Auditor-General was also involved, and ‘required to count the marbles regularly, to ensure that the whole hundred thousand balls were present and correct. If marbles became chipped it was necessary to have the entire set of marbles replaced, a tedious exercise as it was necessary to select wood which would not chip easily.’25

For Public Works Minister Ryan, the Act was an important political lever to wrest control from the 15-member Executive Committee to the Department of Public Works as the consenting authority. But by 1962, the expenditures had started to blow out and Utzon, ‘unable to estimate the total cost… could only say that Sydney would be given the best opera house in the world; costs should be a secondary consideration.’26

Cahill himself had gambled the most by commencing work before Utzon’s designs were complete and before any engineer could actually quantify or advise how to build the behemoth. The ensuing complexity of design and politicisation of the project would see the project budget blow out from the estimated $7 million in 1957 with a completion in 1963; to $102 million, 10 years late and 1,357 per cent over budget.27 But Cahill’s vision in retrospect was lauded as was his ‘moral courage to stand up and say, at a time where there was a housing shortage, ‘No, this is equally important, and we will see it through.’28

The homes the lotteries bought

The impact of the Opera House lotteries on people’s personal finance, fortunes and fates provides a human dimension to how the coffers from Treasury’s bank account changed lives. The perspective of the everyday punters of the Opera House and its lotteries was markedly different from their political masters.

More than 1,250 tickets were sold on the first day of lottery sales on 25 November 1957, and within the month the 100,000-pound lottery (at 5 pounds per ticket) had been over-subscribed. These rice-paper-thin lottery tickets infiltrated homes across New South Wales, and beyond. The news coverage of winners provided endless fodder of people’s different reactions from those who deserved it, to those who didn’t.

The first winner was in the latter category. Oswald Sellers, residing in his mansion at Point Piper, was a company director of a number of enterprises, including chocolate favourites Polly Waffle and Violet Crumble. Notoriously suspicious of reporters he allowed a press conference outside his house until a reporter asked where the winning ticket was and Sellers angrily retorted ‘Who do you think you’re quizzing, go to hell!’ 29 Further west in regional New South Wales, punters like retired grazier C. S. Robertson Mittagong rejoiced ‘I have never had so much money in my life… this will help me move out of this hick town.’30

Unimaginable now was the fact that people’s details were printed in the newspaper. This allowed the media to doorstop winners and grab the live reactions. But the tragic consequences of lack of privacy were writ large when the 10th draw of the lottery was won by Bazil and Freda Thorne in June 1960. A few weeks later, their eight-year-old child Graeme was kidnapped with a ransom demand of 25,000 pounds. Graeme’s body was found six weeks later dumped in a blanket at Seaforth and Stephen Bradley was convicted of his murder in 1961. The case haunted Australia and has been described as the event that ended Australia’s innocence and introduced the concept of ‘stranger danger’ to the country.31

For the people that had the least, the lottery had the power to shift intergenerational inequality. Peter Mitchell is the son of migrant parents, Sandra and Steven Megalooikonomou (who anglicised the name to Mitchell). Sandra left war torn Greece when she was 16 with her sister Poppy. They were held in a camp in Port Said, Egypt, before gaining passage to Australia. Sandra married Steven, moving to Campbelltown where they ran a fish and chip shop. They bought a lottery in 1958, ticket winning the largest prize of $200,000. Peter, who was only two years old at the time, recounted how it changed his parents’ lives:

Understandably contributing to the nation’s premier cultural institution wasn’t at the forefront of their motivation:

It enabled Sandra and Steven to buy a house in Bathurst Street, Liverpool and shopfronts in Campbelltown: ‘As a result of that lotto win, we were able to secure a financial future not only for themselves but for myself and my children and grandchildren.’34

Though on paper Treasury’s role represents just a mechanism of the Opera House Act, the legacy of the lottery radiated out from funding the construction of the Opera House itself into the building and buying of individual homes; the transformation of people’s fortunes and binding these stories into the mythology of the Opera House for years to come.