Request accessible format of this publication.

4. The Treasury and the expansion of ‘the Rail’

Author: Garry Wotherspoon

Hear directly from the author

The advent of responsible government in the colony of New South Wales in 1856 was undoubtedly widely welcomed and appropriately celebrated, but it was not without its problems, particularly for ‘the political class’.

In the first decade, governments came and went with some rapidity.1 It was almost ‘musical chairs’ between the Cowper, Martin and Robertson administrations.

Treasurers likewise had a rapid turnover: there were eight in the first eight years of responsible government, some lasting only several months. And with the removal of the firm hand of the Colonial Office on New South Wales, there were problems for those in charge of the new departments. It was imperative that there be a consistent bureaucracy of trained officials to continue their advisory role behind the scenes.

This was true of the Treasury. The appointment of Henry Lane as the first Under-Secretary of Treasury in September 1856 marked a positive shift in the appointments of Treasury staff. No longer was ‘ministerial patronage’ to be a deciding factor. Lane already had long experience in the Audit Office, and had also served as Secretary to the Board of Enquiry into the Accounts of the Collector of Customs. 2 But there were still issues, and a competent Treasurer from among the elected representatives needed to be appointedto oversee the Department. Geoffrey Eager was an obvious choice. Indeed, as P. N. Lamb has written in the Australian Dictionary of Biography, ‘When James Martin replaced Cowper as Premier in October 1863, he selected Eagar as Colonial Treasurer in the knowledge that no member of the assembly was better equipped to deal with budgetary difficulties and administrative inefficiency in the Treasury and related departments.’3

It was imperative that such reforms occur. The Colonial Treasury had the responsibility to advise the elected politicians about how to both raise revenue from various sources and how to spend this money judiciously. In the early years of responsible government, the colony’s main sources of funds were land revenues, customs duties, various taxes and – eventually – overseas borrowing to finance infrastructure, such as port facilities, bridges and railways. Since New South Wales earned substantial revenues from customs duties, it was committed to international trade, although by the later years of the century, ‘as government responsibilities expanded and became more expensive and complicated’, protectionist arguments ‘for the diversification of the revenue base by fostering local industry and employment opportunities’ became more pertinent.4

Treasurers, then, and their department, were always intimately involved in the decision-making about the colony’s economic life, and Geoffrey Eagar is a Treasurer who perhaps exemplified how to forcefully engage with that role.

Eagar was Treasurer from October 1863 to February 1865 and then again from January 1866 to October 1868, two critical phases in the colony’s economic expansion, particularly with the implementation of the Crown Lands Acts 1861 – also known as the Robertson Land Acts – bringing in new revenues to the Treasury. He was ever alert to actions that went against the financial interests of the colony. When the Trustees of the Savings Bank of NSW chose in 1866 to continue to hold Queensland Government debentures, while refusing to take up any further New South Wales Government debentures, this ‘drew forth a bitter attack from the colonial Treasury’.5 It was inconceivable that deposits in a bank in the colony could be used for the financial advantage of another colony. It was issues like this that led the Treasurer to introduce legislation to set up the Government Savings Bank of New South Wales, opened in 18716 .

Eagar was responsible for ‘the creation of a powerful Treasury organisation’. And to ensure that ‘accountability, transparency, economic efficiency and effectiveness’ were to be the cornerstones of Treasury’s procedures,7 even the ‘life-style’ of Treasury clerks was kept under observation, with betting or gambling ‘in the office’ being watched out for.

‘The regulations prohibiting such behaviour’, as Roberta Carew has observed, ‘were not formalized but all clerks were cognizant of the rules of employment. Private conduct was not addressed by printed regulations, as were the instructions concerning professional duties.’8 Eagar also ‘believed that the government should play a major role in promoting economic growth, mainly by the judicious construction of public works and a carefully devised fiscal policy’.9 And for a colony keen to open up usable land beyond the ranges and along the coast, what better way to overcome the ‘tyranny of distance’ than by the expansion of the rail network to facilitate the export of the fruits of the colonists’ labour?

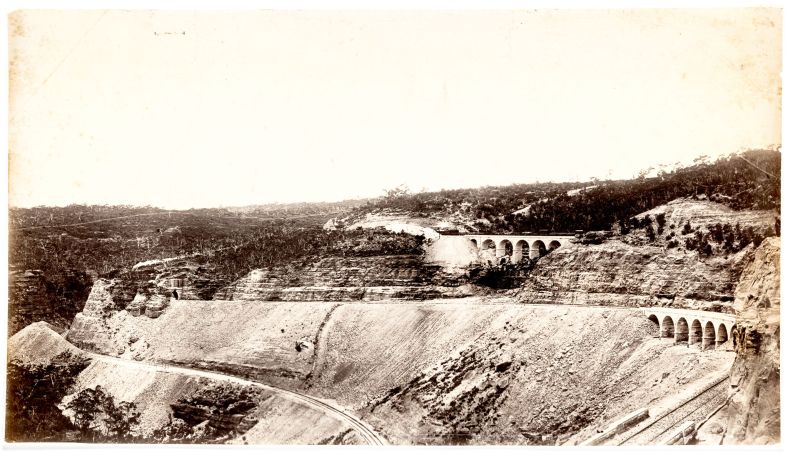

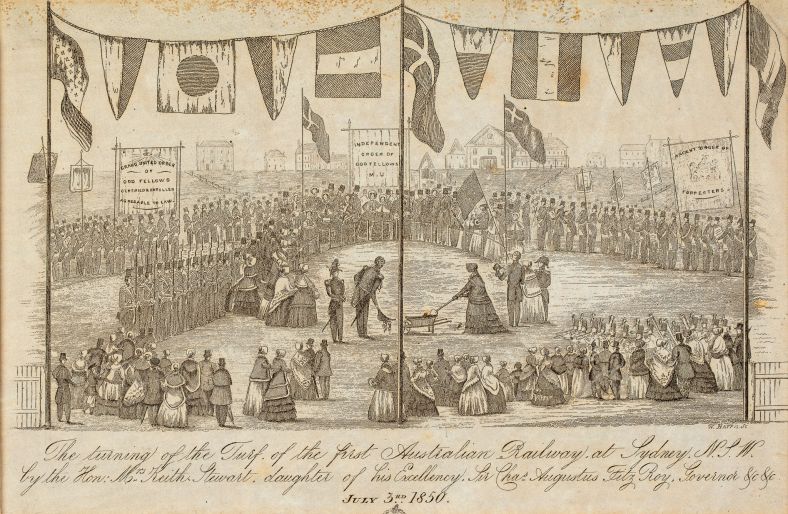

After its success in Britain, ‘the Rail’ had come to the colony early, with plans to link the wool-growing areas of the interior with the coastal ports, to allow the wool clip to get to England faster. While proposals to build railways in New South Wales first emerged in 1841, it was at a public meeting on 24 January 1848 that a surveyor's report on the route for a railway from Sydney to Goulburn was presented, and the prospectus for the Sydney Tramroad and Railway Company was issued on 31 October 1848.

This project, started by private entrepreneurs, eventually collapsed, and it fell to the government to become involved to provide what was increasingly seen as a very necessary addition to the colony’s infrastructure. In December 1854, an Act authorizing the government’s purchase of the Sydney Railway Company was passed, and the assets were formally transferred to government on 3 September 1855.10

There was an initial burst of activity, with the Sydney to Parramatta line opening in 1855, and ‘an extension from Granville to Liverpool was opened in 1856 and extended to Campbelltown in 1858.’ The line from Parramatta to Penrith was completed in 1861.11 Their purpose was primarily the transport of goods to and from the reaches of the Cumberland Plain to Sydney, with its warehouses, port facilities of hydraulic and steam cranes and ancillary services, and the commercial ties for the export industries – provided by the city’s banks, insurance and shipping companies.

For the Treasury, the linkage effects of these to the wider Sydney economy also generated sources of revenue. A branch line to Darling Harbour was included fairly early in the planning, utilizing an area of undeveloped land on the periphery of the city boundary, where the teamsters who transported goods into and out of the city rested their horses and bullocks.

There was a great incentive to get railways constructed, especially out into the interior beyond the mountains. Transport for crossing the Dividing Range before railways was both expensive and slow. Even as late as 1857, heavy goods took on average 23 days to get from Sydney to Bathurst, and cost 15 pounds 10 shillings per ton (approximately $3,000 in today’s money).12 Part of the reason was the poor quality of the roads, and this also meant that horses were not the best animals, bullocks being far better suited to drawing the heavy loads. The cost of drays was also high.

And so a series of ‘Great Trunk Lines’ were planned: one to the south, one west and one to the north, replicating the existing but problem-fraught road network. And surely it was no coincidence that they typically followed the local First Peoples’ songlines, which had connected them to Country, having been passed down from person to person over thousands of years.13 These were clearly the best way to traverse the often-challenging terrain.14

But while the newcomers might benefit from past knowledge, they paid no compensation to the traditional aboriginal owners whose lands were being crossed,15 and for whom ‘Country’ was a functional part of broader cultural and ecological systems. The concept of ‘terra nullius’ prevailed, with railways being the first step in the process of destruction of a whole way of life that had existed for millennia.

As for the possible involvement of the local indigenous people in railway construction through their lands, John Maynard notes that ‘very few people are aware of the long Aboriginal connection to working on the local railway’,16 and while there is much evidence that, in later periods – certainly during the 20th century – Aboriginals were employed to work on the laying of lines,17 it is difficult to ascertain details of this for the late 19th century. Keeping records of casual local railway employees was never a bureaucratic priority.

But they were certainly employed in other areas involved in the construction of railways. As Anita Heiss notes, ‘many Aboriginal people had jobs relying on manual and hard labour, and Eveleigh railway yards was Sydney’s largest employer from the time it opened’.18 And from 1882,19 this was an opportunity not to be missed for Aboriginal men, seeking work after being displaced from their traditional lands.

While ‘the Rail’ was epochally important in colonial history, the ‘iron horse’ represented a new wave of the colonisation of Aboriginal lands. From the outset, the primary aim of the colony’s railways was to both open the interior up for closer settlement and to assist the resultant inland primary producers to transport their produce rapidly to the port of Sydney for export. Progress was slow, especially with the high cost of building the main lines over the Dividing Range. But once the mountains had been conquered, the pace of construction quickened and costs were reduced. This was an important development with beneficial results for Treasury after the Robertson Land Acts of 1861 opened up the interior, generating revenue from land sales and leases and from the wool sales via Sydney’s commercial interests.

It was expected that eventually railways would be a paying proposition.20 But Treasury knew that this might take time. ‘While aware that in the short-run the lines must operate at a loss,’ according to Railway Commissioner John Rae, ‘it was expected that, with the growth in the volume of traffic… earnings would not only cover working expenses, but also service the debt by which such railway construction was financed’.21

Ensuring that the sources of revenue for the colony were protected was an important aspect from the start of railway construction. Initially there was little concern about the produce from along the coast from as far north as Moreton Bay down to Twofold Bay in the south. The coastal shipping trade ensured that goods from the Tweed, Hastings, Hunter and Manning Rivers regions were brought to Sydney, as they were from the south.22 But after Queensland became a separate colony in 1859, Newcastle assumed a greater role in the collection of goods from the interior via the Hunter Valley, and a line connecting Sydney to Wallsend was completed in 1888, to ensure that all colonial goods from the north passed through the port of Sydney.23 The first North Coast railway was opened between Murwillumbah, Byron Bay and Lismore in 1894, probably to facilitate the transport of timber to the coast.

There were two main periods of rail expansion in the colony in the late 19th century and there were clear financial imperatives behind them. There was an initial spurt of activity in the late 1860s, when Colonial Treasurer Geoffrey Eagar was at the helm, evident on all three trunk lines; then a boom of major proportions from the late 1870s to the late 1880s, more prolonged on the northern and southern lines, reflecting responses to the pressures of intercolonial trade rivalry from Queensland and Victoria.24 Implicit in all this expansion was the Treasury’s interest: to protect the revenue flows for New South Wales.

When there appeared to be a threat, action would soon follow, as occurred with the Riverina area of southern New South Wales. The area had been settled in the early 1830s and had developed rapidly as a pastoral district, although population was sparse until the 1850s. But as the area developed, so too did its trade links with Melbourne, the nearest large port. And with the rapid growth of inland river transport from the late 1850s, South Australia also began to benefit, with the Murray-Darling emptying into the Southern Ocean in South Australia.R.H.T. Smith, ‘Commodity Movements in Southern New South Wales’, PhD thesis, Department of Geography, Australian National University, 1961, particularly chapter 2.

Table 4.1 Sources of Revenue New South Wales Government 1856-1871 (all figures are thousands of pounds)

| Year | Customs duties | Total tax revenue | Land sales and leases (net) | Loan receipts (net) |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1856 | 3,258,312 | 1,256,358 | 207 | 856 |

| 1860 | 1,258,782 | 3,258,312 | 310 | 163 |

| 1865 | 1,256,358 | 365,874 | 526 | 427 |

| 1870 | 8,235,698 | 3,258,741 | 463 | 135 |

| 1871 | 3,256,972 | 1,256,358 | 482 | 933 |

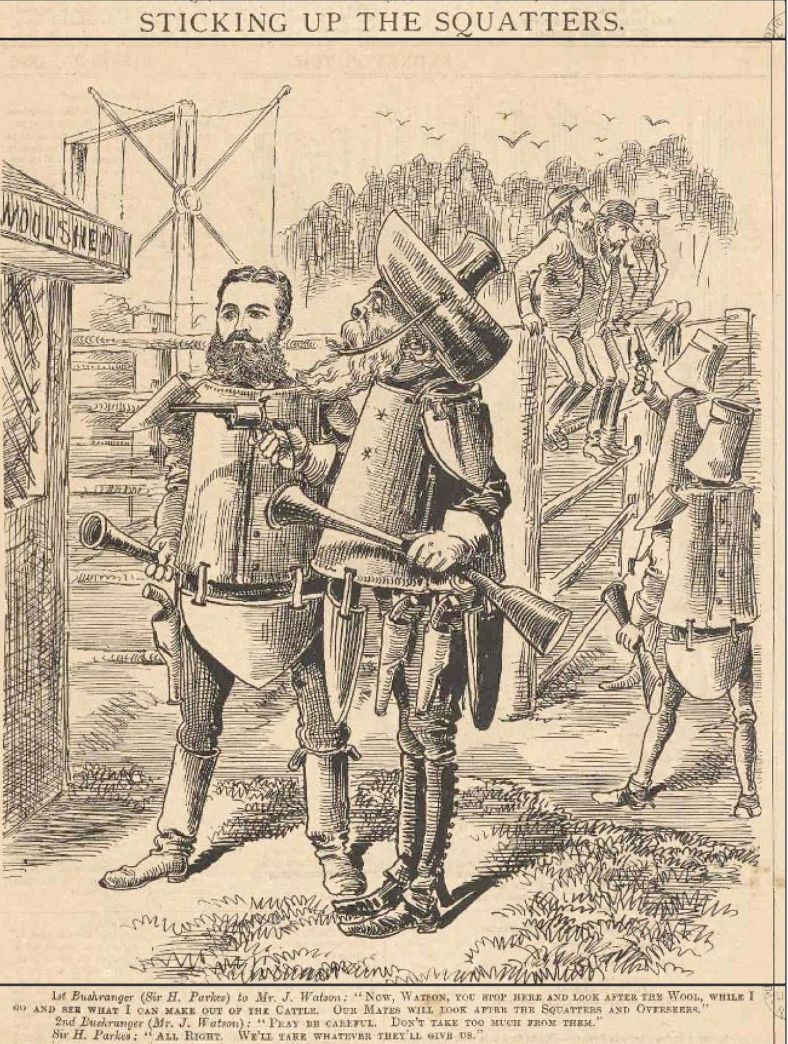

Victoria had already entered the battle for the Riverina goods trade, with its first line from Melbourne to Echuca on the Murray opening in 1864. The Echuca line appears to have enhanced the importance of that port for several decades, as goods to and from properties in nearby areas were transhipped from rail to rivercraft and vice versa.26 It was a move by dissatisfied settlers of the Riverina in 1866 to have the area declared a separate colony that induced the NSW Government to pay quick attention to their grievances, particularly over the disparity between the revenue raised from taxation and land rentals there, and transport facilities provided from these revenues.

This was not a threat to be taken lightly. Less than a decade earlier, in 1859, the colony of Queensland was formally separated from New South Wales. And when there was discussion in Victoria about a second line from Melbourne to Wodonga – completed in 1875 – it became imperative that the NSW Government push ahead with expansion of the Great Southern Line, which, by that year, had not progressed beyond Goulburn, only reached in 1873. Victoria, too, was aggressively pushing forward, with new lines to Wahgunyah (1879), Yarrawonga (1886), Cobram (1888) and Koondrook and Swan Hill (1890).27

In response, the NSW Government pushed construction forward in the Riverina, reaching Cootamundra, Junee and Wagga in 1878, Albury and Narrandera in 1881, Hay in 1882 and Jerilderie in 1884.28 But this was only part of an ongoing bitter struggle. Since the distance from Melbourne to the Riverina was far less than from Sydney, Victoria then passed on the lower transport costs in lower freight charges. New South Wales responded with a system of differential tariffs that favoured goods sent over long distances, and Victoria retaliated with rebates on its charges, and these were quite effective.29 Pressure from Victorian merchants continued, and it was not until 1905 that an agreement was reached between the railways of New South Wales, Victoria and South Australia, and ratified by the state parliaments.30

Another issue they had to deal with was the Darling riverboat trade. After the Dividing Range was crossed and the western plains opened up – with population growth and a rapidly developing pastoral industry, as well as farming of various sorts – cheap water transport allowed the riverboats to transport various products up and down the Darling River. And there was an obvious problem for the NSW Treasury; the river flowed westward and emptied into the Southern Ocean, in South Australia, and what happened to these goods then brought little economic benefit to New South Wales. Indeed, in the 1860s, South Australia encouraged the growth of the river trade because of the benefits it brought the colony. Because of the river trade, ‘Adelaide merchants began to reap vast profits from the sale of general goods in southern New South Wales, and from various charges on wool which was sent to Adelaide for sale’.31

So while the Darling riverboat trade was a problem, the reliability of the rail would bring a major benefit. ‘Neither road nor river could be relied upon’, wrote Alan Lougheed. ‘The river services were risky at all times and for some routes uninsurable; they were intermittent at best and sometimes unavailable for long periods. The risk of losses through shipwreck and the costs of prolonged storage when rivers ran dry gave the railways advantages to offset the relatively high railway freights.’32

Road transport – getting the wool clip from the property to the river – was also relatively expensive even for comparatively short distances. And whereas the rivers were immovable, railways could be constructed in such a way as to reduce land transport costs considerably for many rural producers, as had already been demonstrated by the Albury, Narrandera, Jerilderie and the Deniliquin-Moama lines.

Another factor was the long-term cost issues. If railways were not to eventually replace the river traffic, large and increasing annual expenditures would have been required to preserve the navigability of the rivers. Here was a case to be made: of how the new technology could help eliminate the previous comparatively inefficient modes of transport.33 Further, whereas concentration on river transport inevitably tied rural production to certain areas of the colony, the provision of railways was more flexible, and lines could be built into regions which appeared most appropriate for farming.

All these factors came into play when deciding how much rail construction was to take place and where it would best be directed to. So, tapping into the western interior to maximize its attraction to the graziers and farmers by providing a competitive advantage with rail, there was expansion, but it was slower. It only reached Raglan (east of Bathurst) in 1873, and Bathurst and Murrurundi later in that decade, and Parkes, Dubbo, Bourke, Mudgee, Narrabri and Glen Innes in the mid 1880s.34 Perhaps it was the first successful shipment of 40 tons of frozen beef and mutton from Sydney to Britain in 1879 that accounts for the decision to push lines to such towns in the north ‘to gain access to the trade of southern Queensland’.35

Ensuring that the rail guaranteed revenue flows for the NSW Treasury was not without its hiccups. Occasionally there was pressure from politicians to get a railway extension into their electorate, even if there was little financial benefit to be gained. There was ongoing ‘log-rolling’ and ‘pump-priming’ pressures to be dealt with along with a long history of political corruption, forensically investigated in Lesley Muir’s book (em>Shady Acres.36 Indeed, it could be argued that there was no real ‘development’ justification for some of the railway expansion in the late 1880s; much of it was into areas already well served by other modes of transport, either riverboats or the rail networks of other colonies. But it was the potential revenue flows that could eventuate that were Treasury’s main concern.

Conversely, there was the ‘Sydney interest’, and its power worked in favour of trade flows to and from Sydney via rail. The economic historian Noel Butlin suggested that even by the early 1880s ‘the criterion for railway pricing seemed to be simply to encourage metropolitan business (at the expense of railway revenue)’.37 And while the latter issue could be seen as a problem for Treasury, city taxes and port charges ensured that, on the other hand, the metropolitan revenues flowed into their coffers. The fact that all rail lines were tied back to Sydney was clearly a way of ensuring that the financial benefits of the interior’s lucrative commerce were a net gain for the NSW budget, especially since much of this transshipped produce was for export. As T. A. Coghlan noted, ‘for natural facilities for shipping, Sydney stands unrivalled.’38

Table 4.2 Transport costs of goods per ton in New South Wales 1857-1871

| Sydney-Goulburn | Sydney-Bathurst | Newcastle-Murrundi | |

|---|---|---|---|

| 1857 by road | 12 pounds 5 shillings (17.5 days) | 15 pounds 10 shillings (23.5 days) | 9 pounds (21 days) |

| 1864 by road | 3 pounds 5 shillings (7.5 days) | 6 pounds 10 shillings (11 days) | 6 pounds 10 shillings (8 days) |

| 1871 by rail | 2 pounds 8 shillings 7 pence (14 hours) | 2 pounds 12 shillings 5 pence (16 hours) | 2 pounds 3 shillings 7 pence (10 hours) |

Financing these periods of rapid expansion was not a problem, once it was decided that external sources of funds would be accessed, rather than rely on the colony’s own resources. New South Wales was a prosperous colony of an empire on which ‘the sun never set’, and so gaining money from ‘Home’ was simple, with access to the London Capital Market, the largest supplier of global finance in the late 19th century.

The period from the 1860s through to 1890 in New South Wales has been referred to by historians as the ‘First Long Boom’. It was characterised by rapid population growth fuelled particularly by British non-convict migration, by high levels of capital flows from British banking and financial sources and by an increase in wool exports to Britain. The colony’s economy was heavily dependent on its foreign trade: the value of goods passing through the port had risen from a mere 400,000 pounds in 1825 to 52 million pounds in 1898.39

Much of the growth had been fed by capital inflow. Butlin noted the ‘annual nibblings at the London capital market’ by the New South Wales Treasury from the 1860s.40 And even though this was largely a period of cheap capital for the colonies, Butlin also observed that ‘the vigorous policy of public works’ left the colonies ‘with a heavy overseas debt burden’.41 In the period from 1879 to 1886, New South Wales ‘raised some 27 million pounds in overseas loans, and became recognized as one of the largest borrowers to appear regularly on the London capital market’.42 By the 1880s, the public sector accounted for more than 40 per cent of all investment. ‘These were almost entirely funded,’ as Ray Broomhill has written, ‘with public borrowings from British lenders. The extent of public borrowing was enormous. By 1890, the public debt of New South Wales was 49 million pounds, of which 90 per cent had been raised in London’.43

Easy access to such funds could bring its own problems, as George Dibbs found when he became Treasurer in 1883. His Financial Statement in 1884 led to questioning in the Legislative Assembly after his announcement of an anticipated deficit of 1 million pounds. Roberta Carew notes that:

Despite such problems, rail did play its part in another process that was to be of long-term financial benefit to the colony. They were crucial in the process of regional development, allowing for the movement of population and industry out into the regions. As ‘the Rail’ was progressively advanced into the interior and up the coast, it created the opportunity for new ways of living for the myriads of immigrants who came to the colony in those decades, and jobs.When ‘the Rail’ arrived at a rural town, new small-scale industries developed, partly to serve ‘the Rail’, partly to serve the increased population, but also to take advantage of access to local products. Indeed, for the towns in the wheat belt of the interior, ‘the arrival of the railway was a magnet for millers.’ But there could be repercussions for other parts of the rural economy: ‘these developments often heralded the closure of older, less efficient establishments, closer to the cities and increasingly distant from grain crops that spread further and further out into the regions.’45

As the century drew to a close, the colony and its economy were a far cry from what they had been mere decades earlier, and rail had largely brought this about. Though nothing, of course, could have prepared Treasury for the devastation of the 1890s Depression, by the end of the 1880s, warning signs were emerging. ‘Since the mid 1880s, the economy had been in decline. High wages and employment based on land sales and public works peaked in the years 1882-85.’46 Drought in the mid 1880s continued well into the 1890s, causing increasing rural unemployment, and unemployed rural workers moved to Sydney looking for work, with disastrous effects on the city’s economy, already suffering from a downturn in the manufacturing and construction industry by the late 1880s.

Industrial unrest – the shearers’ strike and the maritime strike – added to the turmoil. The colony’s problems were exacerbated from 1890 by the collapse in London of Baring Bros Bank, which led to chaos in world capital markets. Capital flows to borrowers dried up, with early effects on banks and other financial institutions that were heavily geared with debt. By late 1891, two Sydney banks had failed; early in 1892, there was a run on the Savings Bank of NSW. Over the following year other lending institutions, including several ‘land banks’ and some building societies, failed. Then in May 1893, the city’s largest bank, the Commercial Banking Company of Sydney, suspended payments, and other banks had their deposits frozen.47 The colony’s economy was shattered, and it would be well over a decade before it was back on anywhere near a safe footing.

The stark years of the Depression gave many lessons. They illustrated the negative consequences of the colony’s dependency on external sources for both capital and markets, and produced a dramatic loss of confidence by British investors and a consequent withdrawal of funds that devastated the vulnerable colonial economies.48 It also presaged difficult times ahead for NSW Treasury as it ventured into a new century, dealing not only with the immediate consequences of the Depression, but also facing the challenges of Federation and the ensuing battle over free trade and protection.