Request accessible format of this publication.

2. The New South Wales Colonial Treasury before self-government

Author: Carol Liston

As costs rose and the colonial population expanded to include free people, former convicts and their families, the British government wanted to reduce its expenses. With the end of the Napoleonic Wars in 1815, it turned its attention to colonial management, the efficiency of the public service. and the costs of maintaining the prison settlement. Pressure for change in New South Wales was pushed by the opposition in parliament as well as in complaints from colonists. But the colony remained part ‘of an empire tied by paper – instructions, reports, legislation – to its metropolitan heart.’1

The Bigge Inquiry

John Thomas Bigge was appointed in 1819 to a commission of inquiry into the administration of New South Wales. This followed complaints about Governor Macquarie’s policies from colonists with aspirations for greater civic freedoms. Bigge submitted three reports from 1822 to 1823, the third dealing specifically with agriculture and the economy. The evidence he collected provided a detailed description of most aspects of colonial life.

Import duties on alcohol and tobacco, port fees on a range of shipping movements, auction fees, road tolls, market dues and court fines were paid into a Police and Orphan Fund that was used to pay for local salaries and infrastructure. Bigge approved of these arrangements for colonial revenue and expenditure, considering that it was a transparent process and the funds were appropriately used for public purposes.2

Most expenditure involved the Commissariat as the agent of the British Government. Store receipts were issued by the Commissariat for the purchase of goods for government use. These were aggregated into bills on the British Treasury and sent to Britain. A colonial Deputy Commissary General managed these funds. This person was sometimes efficient, sometimes not; sometimes honest, sometimes not.3

Though notionally a sterling economy, like many British colonies there was a shortage of circulating currency. For many transactions, the local population used barter. Governor Macquarie attempted to remedy the absence of a currency with Spanish silver dollars; these dollars were defaced by cutting a hole in them and assigning a fixed value to the two parts: a holey dollar and a dump.

Further economic growth led Macquarie to approve the creation of a joint stock bank with limited liability – the Bank of New South Wales, Australia’s oldest bank and oldest company – in 1817 and he deposited colonial funds there. He also approved a savings bank formed in 1819.

Bigge commented on duties on imported goods, the growth of local produce, the navigation rules for ships of various tonnage and their role in intercolonial, Indo-Pacific and European trade. He considered the impact of the East India Company’s monopoly. The legality of Macquarie’s financial initiatives were disputed in the colonial courts, as was the limited liability status of the Bank of New South Wales and the pardons granted to convicts in the colony. Bigge made several recommendations for new appointments to manage the colony’s finances. These included a Colonial Treasurer, an Inspector of Distilleries, the replacement of the Naval Officer with a Customs Officer, and an audit officer for the Commissariat. Overall, Bigge supported the continuation of convict transportation but saw the potential of the colony for free settlers.4

William Balcombe was appointed Colonial Treasurer in October 1823. The despatch to Governor Sir Thomas Brisbane announcing that the appointment was ‘for the purpose of establishing your government upon a system of more immediate efficiency.’5

Balcombe was in desperate financial circumstances when he was offered the job of Colonial Treasurer in New South Wales. His patron, Sir Thomas Tyrwhitt – Gentleman Black Rod of the House of Lords and a member of the household of the Prince of Wales – intervened on his behalf to secure him an official position.6

Balcombe arrived in Sydney in April 1824 on the same ship that carried the despatch to the governor. Neither Balcombe nor Brisbane were given instructions on what the duties were to be. He rented a house at the corner of O’Connell and Bent Streets. The lower floor operated as the office of the Colonial Treasurer, while the upper floor was the family residence.

The appointment was announced in the beginning of May 1824. Balcombe requested office equipment and an iron chest or safe, and by the end of the month the Colonial Treasurer’s office was ready to issue payments on Tuesdays and Thursdays between 10am and 3pm. Balcombe requested sentries at his office to guard the cash. Later events suggest he did not get a safe and was only intermittently provided with sufficient sentries.7

Brisbane’s suggested annual salary of 1,200 pounds was reduced by the Colonial Office to 1,000 pounds, with a bond of 30,000 pounds for the diligent performance of his duties.8 His clerk, James Stirling Harrison, had extensive accounting experience so could assist with many duties when Balcombe was confined to bed; Balcombe was an invalid from 1826 and died in March 1829.9

William Balcombe: The first Colonial Treasurer

William Balcombe (1779-1829) was appointed by the Colonial Office as the first Colonial Treasurer. He served briefly in the British navy then joined the East India Company and was appointed the Company’s Superintendent of Public Sales in 1807 on St Helena. The defeated Napoleon Bonaparte was exiled to St Helena, and Balcombe’s youngest daughter Betsy was a favourite companion of Napoleon. By 1818 the British authorities were concerned that the Balcombe family was too close to Napoleon. The family left the island in March 1818 under suspicion of treason. Balcombe had lost his job and his home.

Fragmentary changes in financial management

Governor Brisbane assumed office in December 1821. He had been told before leaving London that changes would follow from the Bigge report. Once in the colony, he was informed by those whom Bigge had interviewed about some of the major changes likely to follow the reports. In the meantime he instituted reforms intended to reduce the expenses of the British Government.10

The Commissariat was responsible for the payments that supported the convict establishment and paid the salaries of the officials appointed in England. Governor Macquarie had clashed with the Deputy Commissary General, Frederick Drennan, who had replaced store receipts issued for sales to the government store with his own notes drawn on the British Treasury. Macquarie complained of his activities, and the British Treasury replaced him with William Wemyss who arrived in Sydney in May 1821. Governor Brisbane sent Drennan home under arrest in 1822 when Drennan could not address the deficiencies in his accounts.11

One way to reduce expenses was to limit the bills drawn against the British Treasury by providing an alternative local currency; however, Macquarie’s earlier defaced dollars were insufficient for colonial needs. According to the Bank of New South Wales returns, it held no British gold or silver coins in 1820. Spanish silver dollars were widely used across the colonial world, and in 1822 the Commissariat imported bullion to provide a circulating currency. Wemyss advised Brisbane to convert the colonial financial system from sterling pounds to Spanish dollars, both for accounting purposes and circulating currency.12

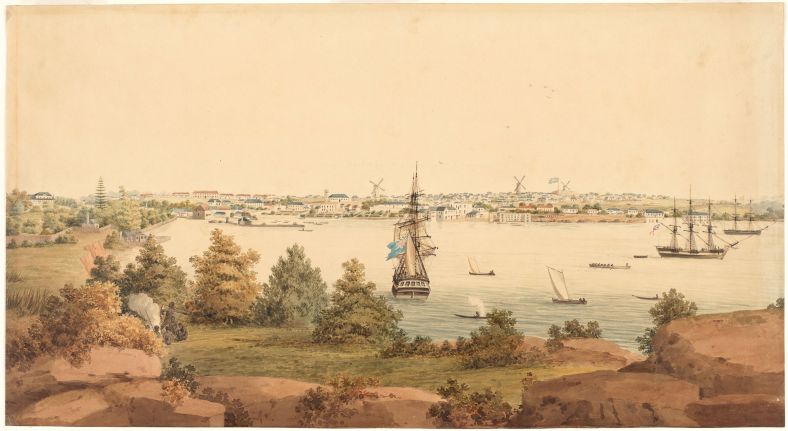

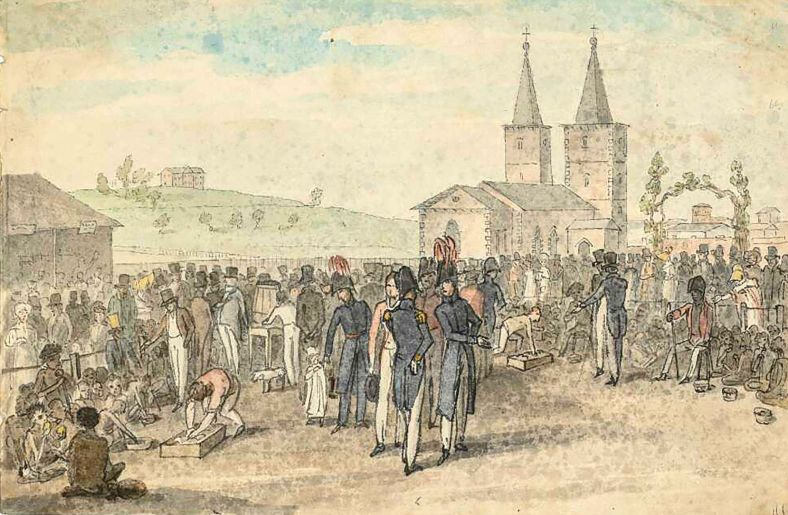

Augustus Earle, circa 1826.

The merchants were outraged, but the Colonial Office supported Brisbane’s decision to move to dollars – provided it was balanced by a tender system to supply the government. Confusion and anger arose when different values were used for the Spanish dollars. The Commissariat paid out in dollars valued at 5 shillings each, but only accepted dollars as payments equal to 4 shillings 2 pence, meaning debtors had to pay more: at 12 pence to a shilling, 20 per cent more.

Moreover, official salaries were paid in dollars valued at 4 shillings each (meaning higher pay) but soldiers in the garrison were only paid in dollars at 4 shillings 8 pence. Further complications arose when payments had been legislated in Britain as pounds, shillings and pence.13

The British Government acted on Commissioner Bigge’s recommendations but in a piecemeal fashion. New legislation, the Act for the Better Administration of New South Wales, was passed in 1823 and provided some momentum for change with the appointment of a Legislative Council of five officials: the Lieutenant Governor, the Chief Justice, the Colonial Secretary, the Principal Surgeon and the Surveyor General. The Colonial Treasurer was not made a member.

The Legislative Council was expanded in July 1825 to seven members, with four forming an executive council and three non-executive members. A further Imperial Act in 1828 added the Colonial Secretary and the Colonial Treasurer as members of both the Legislative Council and the Executive Council. Balcombe died before this change occurred and his successor joined the Executive Council in 1831.14

The Colonial Treasurer replaced the treasurers of the Police Fund and the Orphan Fund and continued the payments previously made from these sources of revenue. Many of these payments were in cash and paid out in Spanish dollars. He paid the salaries of colonial officials and police, though as late as November 1824 the Colonial Treasurer did not have the governor’s warrant to pay the salaries of the civil officers so did not know how much they were to be paid.

He paid the expenses of the orphan schools, provided funds to magistrates to issue rewards for the apprehension of runaways and to the justices for the travelling expenses of witnesses in criminal prosecutions. From the repairs to government boats to the coffins to bury convicts, the Colonial Treasurer dealt with the everyday needs of the colonial administration. He handled some matters of international transfer, such funds that were given to the Colonial agent in England by relatives of convicts.15

The Colonial Treasurer collected the road tolls and market fees which were let by annual tender, slaughtering dues and the hire of convict mechanics. His office issued the spirit licences and beer licences for publicans. Colonial custom was that the clerk in the office received a fee for issuing these licences and that formed part of his salary.

However, the Colonial Treasurer was not responsible for collecting most of the colonial revenue as it was collected by other officers who then paid the income to the Colonial Treasurer. The Sheriff collected court fees; the Surveyor General’s office collected fees on land grants; the Surveyor of Distilleries assessed imported spirits; and the Naval Office collected port fees. Other fees were collected by the Wharfinger, the Postmaster, and the Superintendent of Slaughterhouses. Some of these officials were paid from the fees they collected, rather than allowed a salary. In July 1824, shortly after his appointment, Balcombe noted that he did not have sufficient funds to make the necessary payments until the Naval Officer, Captain John Piper, paid in the balance of funds he had collected.16

Additional officials were appointed by the British government. Bigge had recommended a Surveyor of Distilleries to assess the excise; John Uniacke was appointed in February 1824 on a salary of 200 pounds per year, but died in January 1825.17 He was replaced by Samuel Bate, who arrived in November 1825. Bate previously had an unsuccessful career as a public servant in Hobart and was an incompetent and dissolute appointment.18

Deputy Commissary General Drennan may have been more inefficient than fraudulent, but the appointment of an auditor for the Commissariat accounts was an important step to rectify the situation. William Lithgow arrived in Sydney in May 1824, only a month after Balcombe. Brisbane and Darling were both impressed by his competence. Brisbane appointed him auditor of the colonial accounts in addition to his Commissariat work. The workload was enormous and in 1827 he resigned as assistant commissary general and was appointed auditor-general of the colonial accounts. Lithgow remained in office until 1852.19

The first act of the new Legislative Council on 28 September 1824 was to formalise that British sterling was the official currency but fixed the rate of exchange at 4 shillings 4 pence. This value was later confirmed by British Treasury as equivalent to the silver content. The British Treasury sent silver sterling currency worth 30,000 pounds in late 1825.

Financial awkwardness continued, with payments to the Colonial Treasury made in dollars while the Commissariat paid out in British coin. Colonial accounting returned to sterling and dollars were gradually exported as bullion as more sterling silver was imported.20

Yet for the ordinary colonist, the coins in the till of a Windsor pub in 1830 reveal the miscellany of silver coins still in use: a Portuguese 4 shilling silver piece, a bank token for 3 shillings, two American half crowns, a German coin, a quarter dollar (one of Macquarie’s dumps) a Franc piece, a tenpenny piece, two sterling shillings, and three copper farthings.21 The mixed currency was also a metaphor for social status: children of free British parents were called ‘sterling’, and colonial born children of convict parentage were currency of lesser value.22

Changing attitudes to the payment of officials led to the replacement of the 18th century system of sharing the business profits through fees by establishing salaries for officials. Concerns arose that Balcombe had strayed from this new regime by investing with local merchants as well as placing funds in the bank at a time when it was unstable. He defended his actions as he had received no instructions as to what to do with colonial revenue and had followed the custom of his predecessors. Instructed to remove funds from the Bank of New South Wales, Balcombe had little choice but to keep the funds in his office. He reminded the governor that he had no safe or strong room to store it and requested 20 iron chests large enough to contain the enormous sums of currency he was dealing with, stored in canvas bags. Twelve wooden chests arrived, without padlocks.23

Governor Darling ordered an investigation into the Colonial Treasurer’s premises and staff levels in mid 1826. Balcombe paid 150 pounds per year to rent his house which included his office. Due to concerns about security, he kept the colonial funds in his bedroom. Darling agreed that the Government should pay half this rent and recommended that a building under construction in Barrack Square that was not needed by the military should be completed as offices for the Colonial Treasury, the cash departments of the Commissariat (which had suffered recent burglaries), and the auditor of colonial accounts. The salary of the first Treasury clerk, Harrison, was increased, a second clerk was approved, and Balcombe was authorised to have an additional clerk when needed. Importantly, Balcombe was given the authority to nominate his own clerks, as he was responsible for the performance of their duties.24 When moved to the barracks, the colonial revenue was kept in an iron chest with three padlocks, requiring three key holders to be present when opened.

British financial reforms, 1827

Governor Darling instituted a number of administrative changes that overlapped with reforms under consideration in Britain. Earl Bathurst, Secretary of State for War and the Colonies from 1812 to 1827, was not cooperative with the Lords of the Treasury in their efforts to reform financial matters. However, his successors initiated significant restructuring of the colonial finances from 1827.25

In 1827, a new system of apportioning the expenses of the colony was introduced. Henceforth, the British government would limit its financial contribution to the expenses of the convicts and defence. Salaries of officials appointed by the British government, such as the governor, had been paid by the British government. Darling was informed that 62,000 pounds per year would now be appropriated from the colonial revenues to pay for these salaries.

The British Government, through the Commissariat, would continue to pay for the direct expenses of the convict establishment. However, where the British government had previously paid for many aspects of colonial support, such as police and gaols, these expenses would be progressively transferred to the colonial revenue. The task of disentangling this division of accounts fell to the Colonial Auditor, William Lithgow.26

A large proportion of colonial revenue was raised by customs and excise. As free immigration increased from the mid 1820s, so did the value of goods imported as many immigrants brought their capital in the form of trade goods. In January 1826, the British government established a Customs Department in New South Wales, thereby abolishing the existing role of the Naval Officer. These duties had been carried out by Captain John Piper, appointed Naval Officer in 1813. By the mid 1820s, Piper’s financial affairs were in crisis, so Darling proposed that J. T. Campbell replace Piper. Campbell was to be paid a salary rather than receiving fees. However, the Commissioners of Customs in London appointed Michael Cullen Cotton and Burman Langa as customs officers, and they arrived in January 1829. Cotton subsequently exchanged his post with John Gibbes, who arrived as Customs Officer in 1834 and remained in office until he retired in 1859.27

A significant new source of revenue was created by the sale of land. Previously, land was allocated by free grants on which a quit rent was due; this was troublesome to collect. There was an insatiable demand for land, and Governor Brisbane had been authorised to sell. In 1824, the Surveyor General was directed to collect funds from the sale of land and pay them to the Colonial Treasurer.28 The post of Colonial Collector of Internal Revenue had been proposed by Governor Macquarie but was not created until 1827, when questions about the collection of land revenue by the surveyors were considered. James Busby was appointed temporarily as Collector of Internal Revenue and a member of the Land Board in April 1827. His job was to collect all the miscellaneous revenue, such as tolls and market dues that had previously fallen to Balcombe, as well as quit rents.29

Darling wrote to Earl Bathurst announcing he had created the office of Collector of Internal Revenue and recommending his aide-de-camp, Thomas de la Condamine, for the permanent position. This nomination was rejected by the new Secretary of State, Sir George Murray, who considered that the scale of revenue to be collected by this office required a senior appointment.

William Macpherson, who had heard of Balcombe’s ill health and had applied in London for the job of Colonial Treasurer, was appointed as Collector of Internal Revenue on a salary of 500 pounds per year, and was required to provide personal securities of 5,000 pounds in addition to other securities to a similar amount.30 By the time Macpherson arrived in October 1829, Balcombe had died. The position of Collector of Internal Revenue was ‘extremely arduous’, as he needed to contact all public officers and many colonists in the process of collecting the revenue. In 1830 alone he wrote almost 2,000 letters.31

Campbell Drummond Riddell arrived as the new Colonial Treasurer in 1830 on an annual salary of 1,000 pounds, which he considered insufficient for the duties. His position no longer collected the revenue – as all the detailed work was done by the Collectors of Customs and Internal Revenue – and he had only to receive their payments and make payments as instructed by the Governor. Governor Bourke considered him well paid for his duties. Riddell clashed with Bourke over taking up an additional judicial appointment against Bourke’s wishes, and Bourke suspended him from the Executive Council. The failure of the Colonial Office to support Bourke led to the Governor’s resignation.32

In 1831, as one of the last announcements of Governor Darling, free grants of land ceased. All land was to be sold at public auction at a price fixed by the British government. Significantly, the Colonial Office indicated that – as land was Crown property – all land revenue would form part of the Crown revenues rather than colonial revenues. From the 1830s, this revenue would be used to support free migration to the colony.33

Conclusion: consolidation and retreat

From 1830 the British government had wanted the two divisions of the Colonial Treasury to be consolidated, with both management of colonial revenue and payments from the revenue the responsibility of the Colonial Treasurer. This had been resisted, but in 1837 it was implemented. The position of Collector of Internal Revenue was abolished and the duties transferred to a new Treasury Revenue Branch, with all correspondence going to the Colonial Treasurer. Most of this correspondence involved the sale of land.34

Colonial Treasurer Riddell took leave from 1839 to 1841, during a critical period of change. Transportation of convicts to New South Wales ended in 1840, and the rest of the decade saw the gradual reduction of imperial expenditure on the convict establishment. Officials acting in Riddell’s absence fell ill, and collection of funds such as quit rents were deferred because of the absence of the Colonial Treasurer until 1842. A major economic depression further complicated colonial revenue collection.35

In 1842, an Act of the British parliament introduced a partially elected Legislative Council, but it withheld the power to control the administration and the land revenues. The Colonial Treasurer sat in the new Legislative Council as a nominee of the Governor and was a member of the Executive Council in 1843.36 The 1842 Act provided a schedule for payment of services and salaries from the colonial revenue to pay for the administration of justice, the salaries of the governor and superintendent of Port Phillip, and the staffing of the departments of the Colonial Secretary, the Colonial Treasurer and the Auditor General, with additional funds to support public worship. Other areas of administration, such as Customs and the Post Office, were not included in the schedules.

Frustrated with the limited financial control allowed to the new Legislative Council, the schedules and estimates for 1844 became an opportunity to debate salaries set in London and control of colonial revenues and expenditure. The Legislative Council refused to fund the Surveyor General’s department because its services were used to support imperial income through land sales, while the Colonial Engineer’s department used convict labour on public works, labour that was no longer available as colonial assigned servants. Colonial Treasurer Riddell does not seem to have been an active participant in these debates. The strategy used by Governor George Gipps to retrieve some control of funds for the payment of public servants was to classify various fees as casual revenue of the Crown and therefore not paid into the Colonial Treasury. This effectively reversed many of the measures to consolidate colonial revenue introduced in the 1820s and 1830s.37

A piece of companion legislation, the Waste Lands Act 1842, concerned the categorisation and sale of unneeded land, which provided for half of all the revenue to be spent on bringing migrants from Britain. When Britain increased assisted immigration before the colony had recovered from the depression of the 1840s, the land revenue was not sufficient to cover the costs and expenses had to be paid from the local colonial funds.38 Immigration was funded by issuing colonial debentures in advance of revenue, and this was a stress for Governor Gipps. His controversial policies around the collection of quit rents and licences to occupy Crown lands were intended to increase Crown revenue to support free immigration.39

Major revenue from land was to be spent by Britain; public officers appointed in Britain were to be paid from colonial revenue. Opposition to these policies formed the grievances for the colonists to demand full self-government. The discovery of gold hastened the resolution of these complaints and self-government was established in 1856.