Request accessible format of this publication.

3. The Golden Transformation

Author: Christopher Lloyd

The discovery and early mining of gold in 1851 and following years was one of the most transformative events and processes of Australia’s history. Very rarely have states or territories anywhere experienced the scale of that golden transformation through a peaceful process. The wealth, demographic and political effects were such that the Australian society, economy, polity and institutions experienced rapid shifts to totally new trajectories. Here, indeed, was a striking case of revolutionary non-linearity. To see this, we need to remind ourselves very briefly of the situation in 1850, on the eve of the gold rushes.

The Context of the golden transformation

The European (essentially British) population of Eastern Australia was approximately 330,000 in 1850.1 The Indigenous population, very largely marginalised and excluded from white society, confined to rural and outback locations, numbered perhaps 150,000, spread over the whole continent. These Indigenous people took almost no part in the emergent settler society and economy, still living a semi-traditional life of hunters-gatherers; makers and traders in many places but still highly vulnerable to European diseases, violence and dispossession.2 The European population was already highly urbanised to an extent perhaps unrivalled anywhere else.

The reason for this was the nature of the settler economy that had developed: initially an urban service (criminological) economy out of which grew an export-oriented sector of marine (whale and seal) oil and then wool pastoralism, plus a domestic-oriented sector of food and consumer goods production, and a sector of capital, labour and high-value consumer imports.

Wool was the basis of prosperity for the whole economy, for it had become well-established by the 1840s that Australian wool was essentially unsurpassed in quality on the British market of wool merchants and clothiers. Australian Merino wool was a strategic raw material, along with cotton, in the industrialisation of Britain, the dominant industrial power. Britain’s world dominance in the cloth trade was symbiotic for Australia’s Merino wool producers. The combination of ‘free’ land, a suitable natural landscape and climate, animal selective breeding, vast economies of scale, sufficient and cheap (convict and emancipist) labour for pastoral work (mainly shepherding and shearing), and inflows of merchant capital via local and international banks to allow the constant expansion and/or restocking of sheep stations, had together brought about a vast geographic and economic expansion in the decades after about 1825 until the early 1840s. The pastoral sector had spread over an area much larger than the British Isles, from central Queensland (as it is known today) to the Port Phillip district of modern Victoria and Eastern Van Diemen’s Land (Tasmania). By 1850, there were approximately 15 million sheep grazing in eastern Australia.3

The largest wool producers had essentially ‘stolen’ or squatted on the land they used for their production. Many of these squatters also had legal land holdings in the official settled districts, which were used together to raise capital, build their flocks, and move them to the inland ‘runs’. This economic and political power of wealthy but illegally squatting pastoralists, who had strong support among merchants and shippers in the city of Sydney and in London but not of the Governor, was a direct threat to the governance and finances of the colony.

On the frontier, atavistic, quasi-feudal attitudes in favour of independence and a continuation of a servile labour supply through convict transportation developed. Strangely, this was somewhat similar to the frontier complex in Argentina which was, indeed, an independent state ruled by militaristic forces based on cattle wealth. But a very important difference was that Australia remained a British-ruled possession and with imperial strength in the city of Sydney through liberal semidemocracy and interests aligned with the reformers of the London colonial office. Indigenous/mestizo resistance on the Argentine frontier was sufficiently organised and powerful to induce large-scale military conflict with the expansionist state.4 This was also a significant difference with Australia.

The depression at the end of the pastoral expansion at the beginning of the 1840s and the cessation of convict transportation, however, threatened the economic and political power of the squatters during the 1840s.5 British plans to restart convict transportation at the behest of landowners and squatters were defeated by workingclass and middle-class opposition in Sydney. By 1850, the democratic forces in London and Sydney had moved to achieving limited self-government in New South Wales.

A significant effect of the pastoral economy was the concentration of employment in the city of Sydney and the much smaller urban centres of Hobart and Melbourne. The economic linkage effects in Australia from wool were strongest on the downstream and final demand sides rather than the output (or production) side. That is, most employment was generated in the land transport, wharfage, shipping, finance and other urban services needed by the industry, and the wealth accruing to the squatters was deposited in Sydney banks and largely spent in urban mansions, consumer imports and urban leisure and cultural pursuits. Only later, in the 1870s and 1880s, were large mansions built in the centres of highest quality wool production such as Armidale, Orange, Bathurst, Goulburn and Albury in New South Wales.

The pastoral expansion and New South Wales governance

Institutionally, by the 1840s, New South Wales was still governed ultimately directly from London via the local Governor and his civil and military servants. The Legislative Council (established 1823), however, had been granted a degree of partial democracy in 1842 and more by 1850 (before the gold rush). The British Government had conceded the need for representative government. The wool interest in Sydney and London had together become sufficiently powerful to convince the British state of the necessity to keep the Australian colonial territories loyal to the Crown. By 1855 full self-government had been achieved, including the vital control of the Crown lands.

Prior to the gold effect, the fiscal situation in New South Wales was rudimentary in that the government had very little revenue and very small need for expenditure. The main sources of government revenue before 1850 were land sales for urban and small farmers, import duties and excise taxes. Under the Ripon Regulations from 1831 – designed in part to restrict the spread of settlement and the power and activities of the squatters – small plots of land were sold to immigrants, with the proceeds directed to assisting more free immigration. But a struggle between the squatters and the government ensued, which was largely resolved in favour of the squatters by 1850 through the granting of leases.6

The simple commercial economy and society of the colony in 1850 did require a currency system. Sterling had proved to be unworkable because of a severe shortage. From 1822 it was decided to use discontinued Spanish silver dollar coins as the legal currency. Initially, the middle of some of the large coins were cut out to form a ‘dump’ coin and the remaining ring was designated as the ‘holey dollar’. The value of the whole large coin was generally reckoned to be 5 shillings sterling equivalent.7 But by 1849, the use of these dollars had disappeared, and henceforth only sterling again circulated in the colony.8

With the establishment of the Legislative Council and a growing stream of revenue, particularly from import duties, a new Colonial Treasury was established in Sydney in 1824 that would then bypass the Commissariat as the financial centre of administration.9 By the 1840s, the NSW Treasury was largely independent of the British Treasury except in the matter of Crown land sales.

All of this provides the context for describing and understanding how the gold discoveries affected the governmental institutions of New South Wales, most significantly the finances of the colonial government, and the broader dimensions of the economy and society.

The gold rush

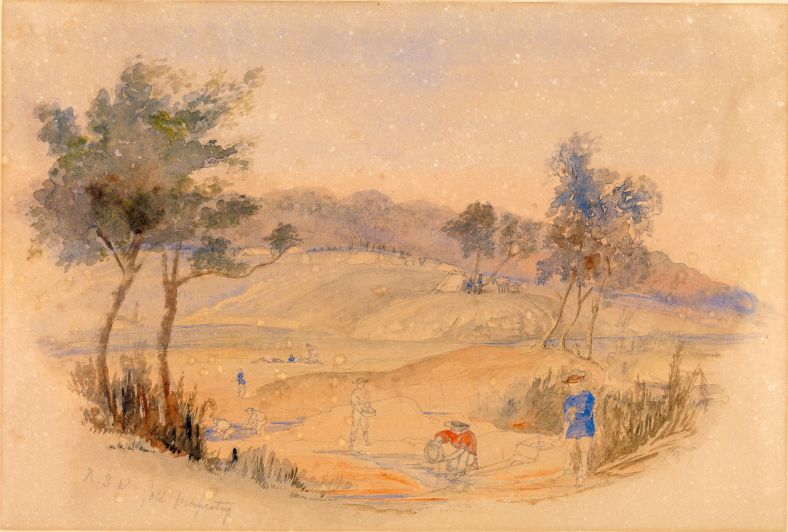

Once it became apparent that there was a real goldfield on Crown land at Ophir, north of Bathurst – confirmed on 22 May 1851 by government geologist Samuel Stutchbury, and to which a seemingly disordered rush of miners had already occurred – the concerned colonial government was forced to act. In Geoffrey Blainey’s words:

However, the institution of the licence fee at the very high price of 30 pounds, payable initially to the gold commissioner of Bathurst, proved to be highly contentious. The licence had to be obtained before mining could begin, but very few potential miners could afford such a fee. Consequently, enforcement of the licence system was very difficult because many men began panning and digging without it. Over time, the licence system – which had also been adopted in Victoria after its separation from New South Wales on 1 July 1851 – was increasingly resented and led to the well-known explosion at the Victorian Eureka goldfield in 1854 where revolting miners fought a bloody battle with the government militia and police. Within a year the fee in Victoria had been reduced to a Miner’s Right of 1 pound per year, and in New South Wales, the fee was abolished in 1857.11

Treasury’s new arrangements for handling gold

The question of control of the newly-mined gold arose immediately once Governor FitzRoy had asserted the Crown’s ownership. This meant that gold could not simply be seized from miners – for then no mining would occur. Gold was supposed to be surrendered to the Gold Commissioner, who would record it and issue an account for the payment to the miner at the fixed price established by the Bank of England of 3 pounds and 4 pence per troy ounce. But some gold was used locally at a discount to buy mining equipment, food and drink, horses, and so on; a miners’ consumer market soon developed. Nevertheless, most gold was initially deposited with the commissioner and then transported under guard to the Treasury in Sydney where it was weighed and recorded.

Thus the NSW Treasury was immediately at the centre of the flow of gold, including the revenue gained by the sale of licences. Nevertheless, ultimate sovereignty over land and minerals did not exist in New South Wales, so the gold belonged to the British Treasury and had to be transported for deposit in the Bank of England, even if deposited temporarily for safe-keeping in the Sydney Treasury’s strong box and in the vaults of local Sydney banks. A new building for the Treasury had commenced in 1849 and opened in Macquarie Street in 1851, soon after the gold rush had commenced.12 (The Treasury building is still there, but is now occupied by the InterContinental Hotel.) This new space enabled an expansion of the activities of the Treasury.

Before long, the volume of gold arriving at the Treasury by late 1851 – with new gold fields opening at Sofala, Goulburn, Braidwood, Wellington and many other places – necessitated new security arrangements. The Treasury decided it could not receive and store all the gold, so it gave this task completely to the Sydney banks. They now had the task of securing, buying and shipping the gold to London. They could not use the gold for currency or loans.13 But British gold sovereigns were arriving in larger quantities in the colony with the gold seekers.

Establishment of the Sydney Mint

The great supply-side shock that the gold discoveries represented had a peculiar effect on the finances and economics of colonial Australia. The peculiarity came from the fact that the gold was not supposed to be used for legal expenditure by miners but had to be surrendered at the fixed price to the Crown as the legal owner, via the colonial authorities, who in turn were required to ship it to the Bank of England in London. The colonial governments in Sydney and Melbourne could not retain most of the gold for their own expenditure – which, in any case, was much more gold than they needed. Thus, the gold did not represent a sudden windfall for the colonial administrations, but it did represent a sudden windfall for the British Government. On the other hand, however, quantities of gold circulated as currency and began to accumulate in the hands of merchants and banks.

The miners themselves were paid for the gold they found, thus greatly adding to the private incomes, expenditure, and investment of much of the population. And since there was no income tax to facilitate the colonial state in capturing a share of the extra income, the wealth effect remained a largely private gain by small-scale miners and local merchants. In fact, the private incomes generated by gold accrued mainly not to most miners but to the sellers to miners of food, alcohol, mining materials, horses, housing, and so on, and ultimately to importers of consumer durable goods, especially luxuries. So it was only through the indirect tax system of excises and import and export duties as well as limited land sales that the colonial government was able to capture a share of the new wealth for expenditure purposes.

Notwithstanding this, the Crown land did belong to the Crown, so the proceeds of small-scale land sales had to be remitted in large part to the British Treasury, the proceeds of which were spent on assisted immigration before 1851. Such was the lure of gold that once the gold rush began there was no need to pay people to migrate, even though assisted immigration did persist until well into the 20th century

Nevertheless, with the great population and economic growth there was a greatly increased need for a larger money supply to facilitate the business of the colony and to enable government expenditure. The British Government agreed in 1853 to the establishment of a branch of the Royal Mint in Sydney, and it began issuing gold sovereigns and half-sovereigns in 1855, thus adding significantly to the money supply of the colony. These coins were worth the equivalent of 20 and 10 shillings and contained 0.2354 and 0.1177 troy ounces of gold respectively. A troy ounce of gold in 1855 was worth between 3 pounds 14 shillings and 3 pounds 18 shillings and 6 pence.14

Demographic transformation and its consequences

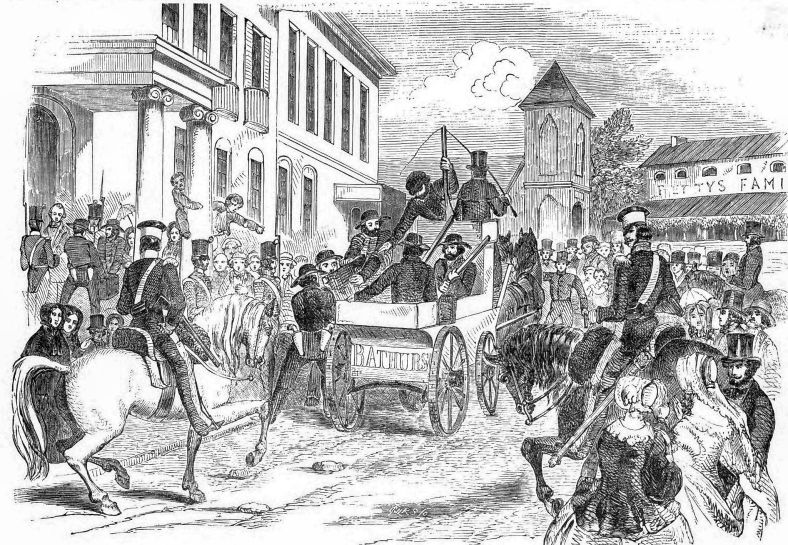

The picture of the general socioeconomic effect of the gold and specifically on government treasury activities was more complicated, however, for the largest effect came not from the gold directly but from the massive demographic transformation that occurred and the consequential geographical and economic spread and development of the population. Sydney (and more so Melbourne) boomed and many inland towns became consolidated as centres of rural and mining industry. Sydney’s population grew from 44,000 in 1851 to 95,000 in 1860, and that of New South Wales from 197,000 to 350,000. Substantial inland and coastal towns developed outside of Sydney. All this urban growth required utility investment: roads, railways, water works, schools, and so on. Government revenue was needed to fund this, but the ability of the Treasury to raise the revenue was very limited, despite the gold bonanza, until the granting of responsible government.

Treasury and responsible government, 1856

Agitation for responsible government (or self-government) had been growing since the 1830s, partly under the guise of liberal agitation but more driven by Sydney-based anti-squatter and anti-transportation interests. The Durham Report of 1839 – which recommended responsible self-government for a newly unified Canadian Province – was strongly influenced by Edward Gibbon Wakefield, a member of Durham’s staff. Wakefield and his theory of systematic colonisation already had considerable influence at the British Colonial Office and had been influential in instituting the Ripon Regulations of 1831 in New South Wales. The colony of South Australia was proclaimed a convict-free settlement in 1836 under Wakefield’s influence with a promise of self-government in the future. A perceived problem in the colony, however, was the relative prevalence of convicts and emancipists in the population.

Certain elite interests in New South Wales saw the opening of the franchise to those ‘lower-class’ people as an unwelcome democratisation – hence the anti- transportation agitation in Sydney. The landed interest, however, supported resumption of transportation to supply labour as shepherds on remote sheep runs. Preventing further labour competition was a motivation for the large-scale protests against the revival of transportation:

The granting of ‘responsible government’ would in effect be the granting of quasiindependence in all matters except foreign affairs and defence, notwithstanding residual powers of the London-appointed Governor. In particular, this meant financial independence and thus a large expansion of the powers and capacities of the colonial Treasury. After much disagreement between the Legislative Council and the British Government, the colonists were permitted to formulate their own constitution with the ultimate approval of the British government. This was achieved in 1855 when the new Constitution established an elected lower house, the Legislative Assembly, with manhood suffrage and secret ballots.

The New South Wales Constitution Act, given Royal Assent on 16 July 1855, was fundamental to the future of the finances of the colony because:

The Colonial Government thereafter had a considerably expanded revenue and corresponding ability to fund its expenditure plans, which mainly involved public works, justice, education and policing to begin with. The building of railways, roads, bridges and schools could be expanded to meet the greatly enhanced and dispersed population. Finally, New South Wales had a locally controlled treasury and revenue stream that matched the attitudes and asperations of what many locals considered to be an emerging new civilisation.

Gold and economic development

Thus the gold rushes transformed the Australian economy in a dramatic fashion, due to the great population growth, the great expansion of rural and industrial production, the great expansion of export income and the influx of capital. Moreover, as Noel Butlin pointed out in his canonical study of Investment in Australian Economic Development, 1860-1900,17 by 1860 the chief consequence of the 1830s-1840s wool boom and the gold decade was that:

Furthermore, as Butlin continued:

![Corner of O’Connell Street & Bent Street [a view], William Butler Simpson, 1853. The building on the left is the house of first Colonial Treasurer William Balcombe - and thus the first headquarters of NSW Treasury](/sites/default/files/styles/content_x1/public/2024-11/Bicentenary-2024-Book-C03-004.jpg?itok=pcm9d50n)

In sum, the central significance of the gold discoveries cannot be doubted: economic and demographic transformation that led rapidly to economic, social and political transformation into an urban-industrial society. By the 1860s the economy and urban structure settled into a more stable pattern of wealth, prosperity and export income that produced the highest incomes per capita in the world by the 1880s. Gold set the foundation, but it was overtaken by the 1870s by wool and other agricultural exports, and by base metal mining by the 1880s. Before long, an assertive labour movement, located particularly within the mining, pastoral, transport and shipping industries, began to develop a new democratic labourist, socialist and nationalist consciousness. Consequentially, a second great transformation, following that of gold, took place in the late 19th and early 20th centuries, this time in politics and socioeconomic policy. But that’s a story beyond the scope of this chapter – even though it can be traced to the emergent political consciousness of the golden era.