Request accessible format of this publication.

5. Compliance, Conflict and Invention, 1880-1918

Author: Roberta Carew

Geoffrey Eagar’s successor, Francis Kirkpatrick, was head of the Treasury at the time.

The 200th anniversary of the foundation of the NSW Treasury in 1824 reconciles the ebbs and flows, the challenges, the resilience of a department from a few rooms underneath private quarters to the current establishment in Sydney, one of multiple levels and employing multiple levels of excellence.

The NSW Treasury has been resilient, weathering the maladroit, the show ponies, the ambivalent, the smartest, flourishing in the wisdom of its Under Secretaries – despite the anomalies. It served the colony from its English tutelage, going by itself alone and accommodating even reluctantly and as suming in 1901 the terms of the Australian model of federalism.

Being the elder of the states’ treasuries, historians must seek evidence of NSW Treasury’s history in documentation held generally in the State Archives. Managerialism in action has been recorded for researchers in its documentation and its methodologies. In this history of the archives, Peter Tyler describes the changing fashions in managerial practice in the NSW public sector. This involved radical changes in reporting practices, innovations and improvements evidenced in the two hundred years since the NSW Treasury deposited its documented administrative history in its array of papers, volumes, tomes and – lately – exemplary use of the latest technology to spread information throughout the community, responsive to public needs.

It is worthwhile to mention an episode in the history of the State Archives which involved Treasury records. A violent windstorm struck the archives building at Kingswood in outer Sydney and partially unroofed it. Hundreds of volumes were exposed to the elements. Archivist Jenni Stapleton recalls the volumes from Treasury of the 1880s ‘the heaviest, ugliest, dirtiest books I’ve ever seen’. But they became her favorite archives because they saved her life: the massive weight of the volumes stacked two metres high against the back wall stopped the whole building from collapsing.1

This chapter analyses the personality of the NSW Treasury and the leaders responsible for its style of management: its adherents, its corpus, its reputation within government and beyond into the social context. Commercial activities, banking, agricultural and domestic interests depended on the veracity of its statements of economic management such as the budget papers. The Under Secretaries’ management and style are revealed for consideration and criticism.

A wearisome decade

On Monday 2 March 1891 at 11am, the Federal Convention opened at Parliament House on Macquarie Street. George Reid and Sir Henry Parkes were hosts to the various representatives of the Australian colonies. The walls of the Legislative Assembly chamber had been the silent witnesses of many proceedings of historical significance – but none had equaled in interest or importance those upon which the Australasian Convention was to meet that day. Its purpose was to consider and report an adequate scheme for a Federal Constitution. On that day the colonies concurred that their best interests and their present and future prosperity ‘will be promoted by an early union under the Crown’.2

Already the administrative roles of both the Federal and state governments had been outlined and discussed, although New South Wales was not convinced of the benefits to be gained from federalism. At a state level it was considered sensible. However, to ‘universally recognise that Free traders and Protectionists alike must recognise the futility [of disagreement] with federation lying close and straight before us, of devising new tariff arrangements which the first duty of federation would be to sweep away and supersede’.3 In summation, the ‘distribution of the revenue surplus, fixed federal subsidies, the transfer of departments to the federal sphere, the consolidation of debts, the disposition of the public debts and assets, all were part of the financial problem’. The doubts of 1891 were evident a century later.4

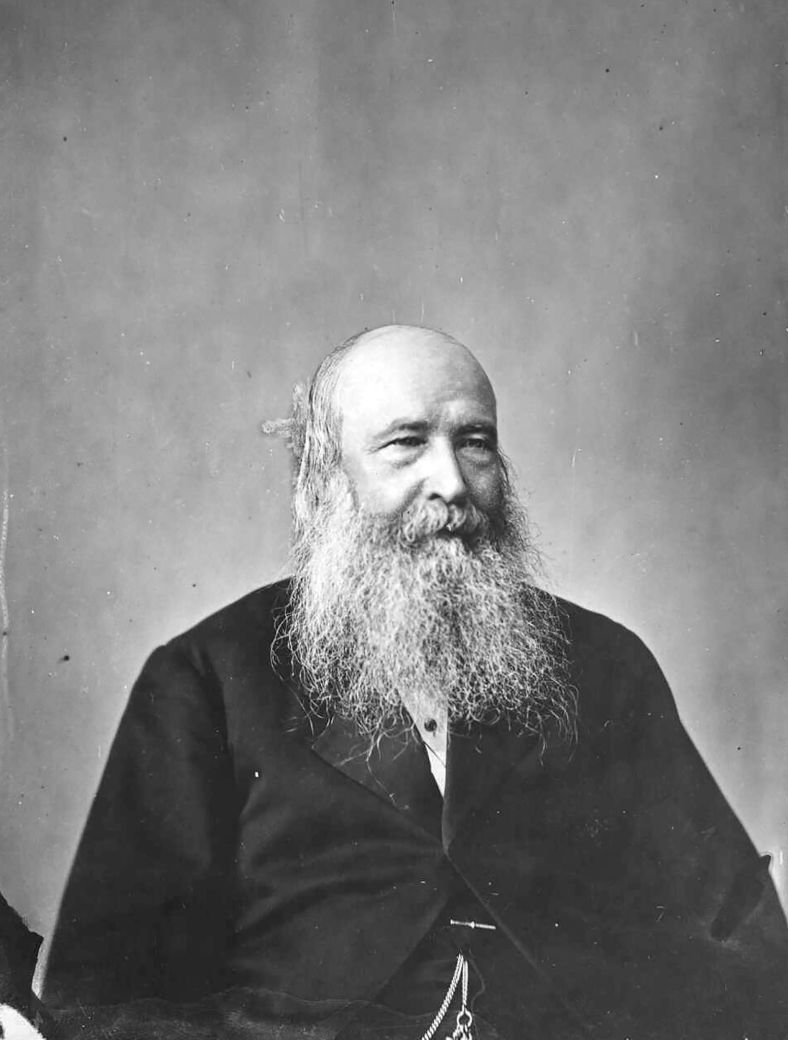

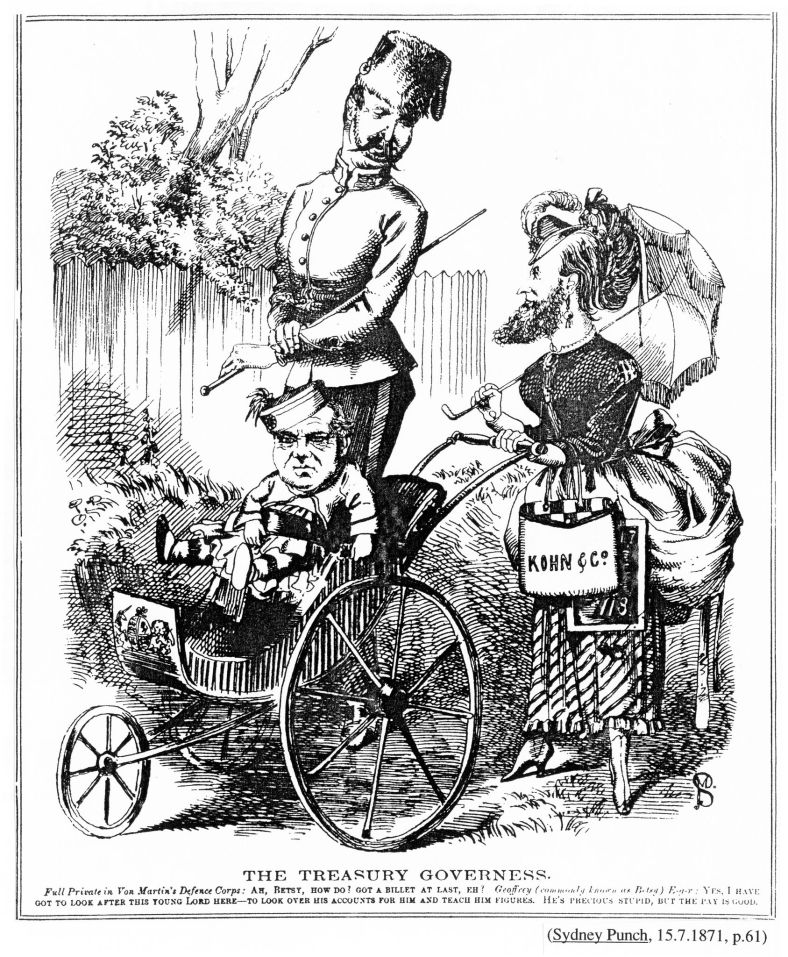

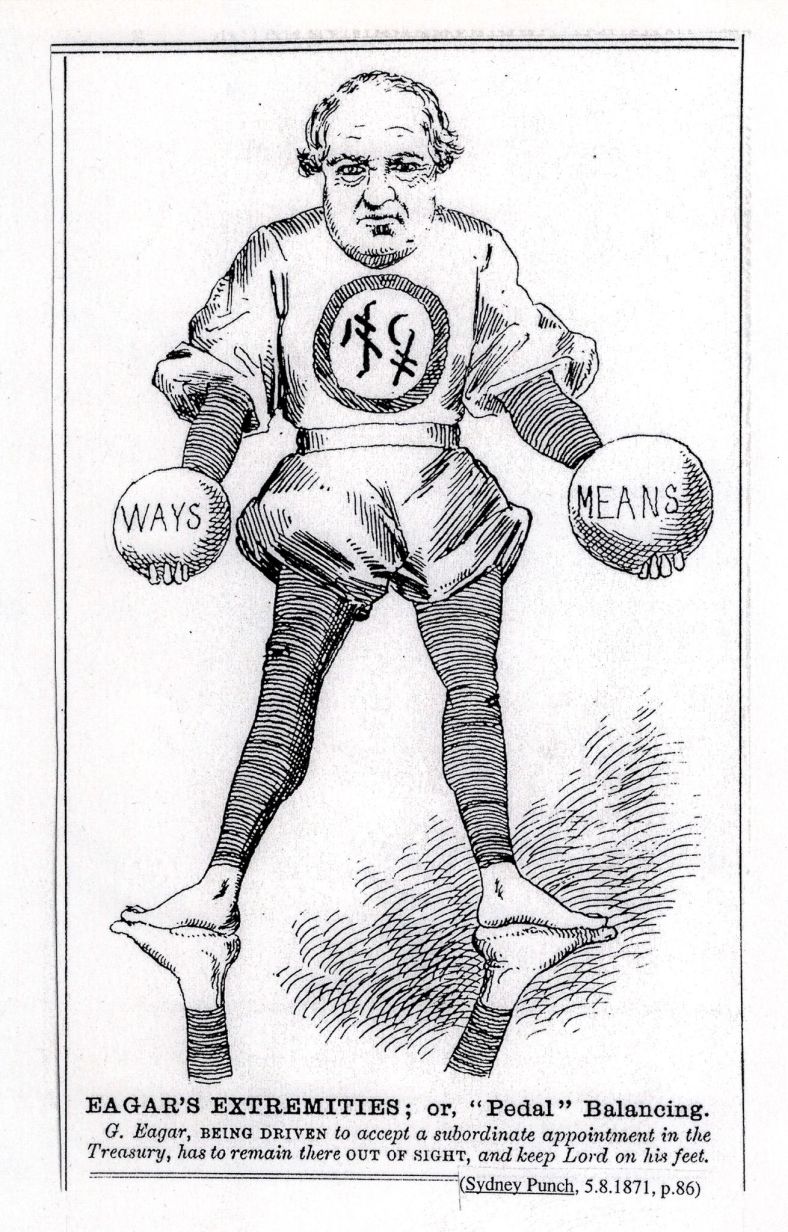

It is coincidental that on the previous Saturday in late February 1891, Geoffrey Eagar – known in his political days as ‘Betsy’ – made his last appearance at Treasury as the Under Secretary of Finance and Trade. It was reported in the Sydney Morning Herald that ‘in the morning the officers of the Department waited upon him and expressed their goodwill for his future welfare and regret at his departure.’ Francis Kirkpatrick assumed the position of Acting Under Secretary.5

In April, a later presentation, an illuminated address and a purse of 185 sovereigns subscribed by Treasury officers was presented to Eagar. He was ‘much affected by this evidence of esteem on the part of those with whom he had been so long and intimately connected and he feelingly acknowledged the compliment.’6

In his private life he was tormented by financial adversity.7 But he shone in the Treasury. P. N. Lamb’s summation of Eagar’s career as Treasurer and Under Secretary of the Treasury was that it was ‘impossible to convey adequately the significance of his control of government policy and the lasting influence of his reforms’.8 His achievements rested on three factors: his reputation as an experienced cabinet minister before joining the Treasury; his profound knowledge of accounting procedures acquired during his career in the banking sector permitting him to achieve mastery over the increasing complexities of government accounting and overseas borrowing; and his support given to 16 ministries between 1871 and 1891.

In the later years of his leadership of Treasury, Eagar’s attention was directed to local cash balances to finance the rapidly mounting capital outlays, land sales, the London Stock Exchange, uneasy indications from the Bank of England, and the floating of a 2 million pound overseas loan. Eagar was remembered kindly and honoured by Sir Henry Parkes in his condolence motion; he requested the House to place on record its sense of loss suffered by Eagar’s death in 1891. Sir Henry said that Eagar was ‘almost the last of a group of men… which watched over the introduction of Parliamentary Government into this colony.9

Eagar has a unique place in Treasury history. He was an elected member of Parliament and Colonial Treasurer between 1863 and 1868, then declared bankrupt, then appointed second Under Secretary for Finance and Trade. Two other men held the position of Treasurer of New South Wales and had been officers of the Treasury Department. Sir George Reid, Treasurer and Premier, was Correspondent Clerk and later acting Accountant of the Treasury between 1869 and 1878 when he became Secretary to the Attorney-General. After a successful career in colonial politics, he entered the Federal Parliament and was Prime Minister of Australia from 1904 to 1905. Sir Bertram Stevens in the 20th century was the Treasury Under Secretary before his dismissal by Jack Lang. He subsequently entered NSW Parliament.

The chronic undulations characteristic of the colonial government between 1871 and 1900 were of such frequency that its effective operation might be doubted, justifiably. Political factions were growing and formalising: the 1885 election would be the last without a recognisable party structure, and the dominant Free Trade and Protectionist parties emerged in 1887.

Economic crises punctuated the yearly Financial Statements during this period. Through the turmoil of failing ministries and succeeding Treasurers, the Treasury was expected to thrive and overcome all resistance to political equilibrium. Political personalities and public inquiries circumscribed problematic leadership and the economic crisis associated with profligate overseas borrowing. All of this contributed to a hiatus in necessary administrative reform compounded by the growing complexity of Government finance.

After 1855 at least eight official inquiries remarked on the functions and management of Treasury. These were crucial to good and reliable governance including information management and upon which the Parliament and more specifically the Treasurers depended so heavily and frequently for timely and dependable advice. The Audit Act 1870 was an initiative of Governor Belmore and intended to mollify the Auditor-General and improve tarnished relations between itself and Treasury. The provisions of the Act rendered the issue of expenditure of public money on a much better footing than he had found it. Belmore was the last of the imperially trained Treasury men. He was educated and tried in financial management. After his departure, Eagar was left to formulate Treasury policy and direction.

Between 1871 and 1900 Treasury underwent a number of foremost examinations into its procedures, functions, structure and standards of accommodation. The notable enquiries included: the Select Commission of Inquiry 1871; the Fitzgerald Report of 1881; a cause célèbre involving the Treasury, the Financial Statement and Dibbs vs The Daily Telegraph; and finally the Commission of Inquiry into the Public Service of 1888. The reason for the inquiries was part of a quickening worldwide interest in increasing the efficiencies of government economic management, increasing debates on the transparency of government activities and the growing complexity of government involvement in international money markets.

The outcome of each inquiry, as with most official inquiries, was variable; opportunities taken for improvements in all activities were usually limited or deferred. It is indisputable that the economy drove and accelerated the disparate functions attached to Treasury’s priorities. The question asked is: how well did Treasury address the fiscal aggression of the latter half of the 19th century?

The brief of the Commission of Inquiry of 1871 was to inquire into the Civil Service, the fifth inquiry involving the Treasury since 1855. The object of the inquiry was ill-defined other than to inquire into the Civil Service. Treasury, though not specifically targeted, received sufficient attention to give evidence of some of its deficiencies. The final report and evidence were published on 5 March 1873. Incidentally the inquiry verified the abrasive relationship existing between the Treasury and the Auditor-General, not resolved by the Audit Act. The Committee found that the permanent public service especially senior positions should be filled by ‘men of ability, character and intelligence, capable of counseling and assisting Ministers particularly when there was a frequent change of Ministries.’10

The Committee examined Treasury procedures, entry examinations and qualifications of its officers, its standards of professionalism, Ministerial patronage, the desirability of a career in Treasury and technology utilised. This latter facility included the recent innovation introduced by Under Secretary Henry Lane such as copying machines. The outcome of this 1871 report was non-conclusive with no outstanding changes introduced.

The Fitzgerald Report of 1881 was an initiative of the New Zealand Auditor-General James Fitzgerald. Commissioned in Wellington in 1880 by the Public Accounts Committee of the New Zealand House of Representatives, this inquiry was convened to assess the standard of government accounting in the Australian colonies and New Zealand.11 In his final report Fitzgerald criticised the management of the public accounts and the audit of the public revenue in most of the Australian colonies. New South Wales failed when the Commissioner applied professional criteria under the Heads of Consolidated Fund, Loan Moneys and Trust Funds. There were no controls in place to prevent the Government from obtaining monies by means other than those provided by Parliament.

Parliament in the 1870s and 1880s remonstrated with Treasury because of its sense of loss of control of the public purse to Treasury contrary to the provisions of the Audit Act. ‘There were deficiencies’, the Auditor-General’s Annual Report of 1881 noted, ‘not escaping the notice of a keen enquirer into our system, sent over from New Zealand’.12 Economic boom in the 1880s was reflected in the increase in record keeping responsibilities and professional expertise not readily available in the middle ranks. The outstanding debt of the colony in December 1883 was 21,632,459 pounds, 9 shillings and 2 pence – attributable to the increasing involvement by the government in communications and public works, a growing population and increasing immigration. Parliamentary Debates between 1871 and 1888 recorded deficiencies in Treasury’s reporting methods.13 It was considered ‘utterly impossible to comprehend from the financial statements made by the Treasury the state of the colony’s finances’.

The Auditor-General agitated for the establishment of a Committee of Public Accounts so that Parliament would have more effective control over public expenditure. The Auditor-General’s report of 1887 regretted that Parliament had not expressed an opinion as to the illegal action of the Treasury in laying its hands on the public revenue without Parliamentary sanction.14 (Before the Treasury Budget Branch was established prior to World War II, Treasurers appointed ad hoc committees or appointed individuals to provide advice on financial matters and made recommendations to the Government as to how reductions in expenditure could be made.)

The 1880s were calamitous for Treasury. Its operations were opened to public scrutiny in the hearing of Dibbs vs The Daily Telegraph. The action became a cause célèbre in the colony following the delivery of the 1885 Financial Statement by the Treasurer, Sir George Dibbs. The case exposed the entire procedure and formality associated with the production by Treasury of the Financial Statement and its delivery by the Treasurer.

During the hearing it became apparent that the manner of keeping records in the Treasury was arcane. Records subpoenaed from Treasury relating to the Treasury’s Chief Accountant and Acting Under Secretary of the Treasury, James Thomson, concerning his involvement in the 1885 budget, together with those pertaining to Premier Jennings and Dibbs between December 1886 and January 1887, were non-existent. There were no records, not even those attached to the 1885 budget papers. The Daily Telegraph could not prove its case because of the destroyed, misplaced or lost records.15 The hearing of Dibbs v The Daily Telegraph was concluded on 7 September 1888 and the jury found in favour of Dibbs and assessed the damages at 100 pounds.

The whereabouts of the Under Secretary Geoffrey Eagar is important, as he did not retire from the Treasury until 1889-90. His motives appear obscure. Premier Jennings might have conducted his own investigation, made a decision and given various orders resolving the issue. Neither Eagar nor Jennings seemed up to the task of taking their subordinates in hand. Eagar remained a shadowy – if not absent – figure during this court action. He was no doubt overwhelmed by his own personal financial problems, leaving the day-to-day conduct of the Department to Thomson.16 (In 1885 the Chief Commissioner of Insolvent Estates gave notice of the sequestration of his estate.)17 Would this matter have progressed further than a squabble within the Treasury and Thomson’s professional hurt placated by strong and determined leadership? Dibbs’ litigious nature encouraged by political factions carried the antagonists firmly over the Rubicon to litigation.

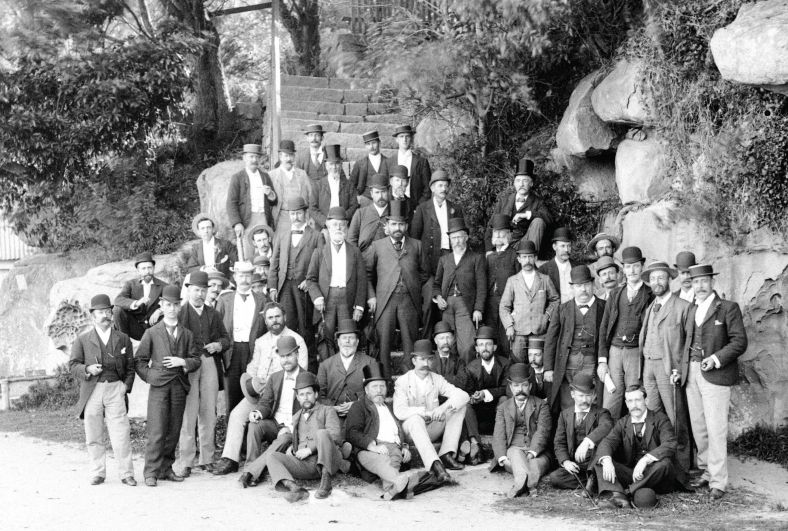

Because of the growth in the complexity of its responsibilities by 1888 Treasury had been divided into eight divisions: the Ministerial or Administrative Office, Account Branch, Revenue Branch, Pay Branch, Examining Branch, Correspondence and Contract Branch, Records Branch, Inspecting Branch, and finally the support Branch of Messengers and Housekeepers.18 Women were yet to be employed. In 1891, the Sydney Typewriting Association argued its case for female employment. Appointments as typewriters in government and other departments in Sydney ‘was peculiarly suitable for ladies of education, is remunerative and pleasant… In London, the Treasury, Whitehall and other Government offices have unanimously adopted the idea of employing women as typewriters.’19 Except for Elizabeth Minnie (née Eade, born 1885) who was appointed the first female typist in 1908 and a handful of cleaners – six in 1913 – women remained largely absent from Treasury personnel (which numbered 109 in that year) for decades.20

The 1888 Commission of Inquiry into the Public Service referred to the problems between Treasury and the Audit Office. The Inquiry extended over four years. George Dibbs described it as ‘an interminable commission’ and wished it would cease.21 The Commission found that major administrative reform within the Treasury depended on the erection of a new Treasury building. The Commission noted the small rooms, narrow passageways, a lack of suitable strong rooms and fire-resistant safes for the safe custody of important documents and records. The Commission’s report on Treasury staff was, however, favorable. Treasury conducted its business in an efficient manner and the senior officers were trustworthy and efficient. There were, however, too many clerks to guard against error or fraud creating unnecessary work. The Treasury, however, lacked firm leadership at the political and administrative level.

In 1892 questions were raised again as to the Treasury’s accounting system.22 In 1895 George Reid’s Ministry changed the financial year to end at close of business on 30 June, not 31 December, a practice that had been inherited from British tradition. (This was done to save the parliament having to sit over an Australian summer to pass the Budget.)23 A new system of appropriation and application of the public moneys to public purposes made the receipts and payments within a defined financial period a basis for arranging the finances of the Colony. Nevertheless, the true financial position of the colony from a perusal of the government accounts as they were then submitted was beyond the understanding of most citizens. In 1895 Reid established the system of direct taxation for the first time and the position of Commissioner of Taxation was created within Treasury. Land tax was introduced in the same year.

In 1898 Reid responded again to the need for financial finesse. He introduced a further amendment to the Audit Act 1870 which provided a further statutory basis by which the public accounts were to be kept, audited and presented in a statutory form. At the turn of the century the overall problems of accounting remained, apparently insoluble. A complaint as to the presentation of the Public Accounts was repeated in the Assembly on a hot December night in 1899 during the debate concerning William Lyne’s Financial Statement.24 Did the balance at the credit of the Consolidated Revenue Fund Account on 30 June 1899 represent a fair and true statement of an actual surplus of revenue over expenditure for the previous four years during which the Cash System had been introduced?25

The 19th century closed on the cusp of a further inquiry into the management by the Treasury of the colony’s finances. It was apparent, indeed essential, more so now than previously, for Treasury to be led by men (because only men were considered) of superior professional standing and leadership. Treasurers generally lacked a close affinity with dense figures and accounting principles. Without men of substance in the permanent public service, the Ministries would have foundered attempting to comprehend the financial complexities of loan and revenue raising and expenditure. They needed to balance the threat of bankruptcy with the prodigal spending associated with the development of the colony in the late 19th century.

True financial and economic reform of the Treasury, however, was not achieved until well into the 20th century when modern principles of economic reform and management were explored and applied. The 20th century initiated robust change to the economic management of New South Wales circumscribed as it was by federal politics and federalism.26

Federalism and the Treasury

What could be said was that the Commonwealth Bill in its financial clauses was unfair, but not final. It offered no security to states’ interests and would ultimately lead to constant bickering. During the federation debates financial commentators correctly anticipated that there would always be a struggle between the states to obtain an equitable share of the surplus funds to be returned to the states. This was the crux of the financial debates.

It was Western Australia that remained unresolved because of the financial provisions, but that was of little moment for the other states. In April 1933, under a Labor Government, in a compulsory referendum its peoples voted heavily in favour of seceding from the Commonwealth: 68 per cent of 237,198 voters. The House of Commons rejected the subsequent submission, but the issue remains a constant irritant for the Australian Government. Its most recent revival occurred during the COVID-19 pandemic and its hard border closures.28

The problems New South Wales faced over the last decade of the 19th century were common to all Australian colonies. The thinking behind the federal debates reflected their individual responses to domestic social, economic, financial and political conditions. In August 1891 the Bank of Van Diemen’s Land – the second oldest bank in Australia – failed, together with three banks in Melbourne and one in Sydney in a disastrous depression. Labour unrest prevailed throughout the country over that decade with increasing unemployment and further bank closures.

Sir Samuel Griffith demonstrated the unfairness of the Sydney Convention scheme of 1891. He opined that ‘one weak point evidently is that, while the Federal expenditure is charged in proportion to population, many of the expenses of Federal administration may be heaviest where the people are few’.29

William McMillan, merchant and former NSW Treasurer, observed with prescience that ‘it is not so much a question of the difficulties which meet us, but the caliber of the men who will have to solve them’.30 In March 1897, Edmund Barton, ‘distinguished university graduate, a promising barrister with a fine voice, manner and appearance’, presented the individual colonial nominations for the various Committees: the Constitutional, Finance and Judiciary Committees. (The Finance Committee considered, inter alia, provisions relating to finance, taxation, railways and trade regulation.)31 Was the fiscal question reduced to James Service famous as ‘the lion in the way of Federation’? Or were states’ rights the lions in the path, unwittingly separating the issue of states, rights from fiscal issues, a natural and indissoluble symbiosis?32

The Australian Federation was established under the Commonwealth of Australia Constitution Act 1900. This was an Act of the British Parliament. The Australian Government imposed a broad and composite control of the individual state’s finances thus reducing the political status of the federated states to what may be described as a mendicant affiliation. Alfred Deakin opined that the Constitution ‘left them legally free but financially bound to the chariot wheels of the central government.’33

Federation Day was a public holiday, and the Under Secretary Kirkpatrick requested six additional constables to guard the Treasury building during the Commonwealth procession. He could not guarantee the safety of important records if public unrest occurred. The procession passed and no untoward behavior reported.34

The Federation introduced financial complexities of a nature not encountered by the Treasury before. In tandem with this superscript of negotiation and compromise with the federal treasury was the ritual of constant but transitory changes following enquiries into the structure and management of Treasury. The principles of administrative reform were not readily available to the public service of the colony. Towards the latter half of the 19th century, Ministries in New South Wales came and went with bewildering frequency. Firm leadership of Treasury was ephemeral and not feasible. A major reason being that ‘contextual complexities are crucial determinants in the success or failure of reforms’. Government stability is essential, and reform is only successful when both leadership and time are favorable. Broad revolutionary administrative reform was therefore not feasible in 19th-century New South Wales.35

Between 1824 and 1900 responsibility for revenue raising and government expenditure remained the common threads generating and prioritising Treasury’s activities. This emphasis shifted in the 20th century. Federal–state financial relations and associated policy and stratagems displaced and dominated the previous focus in the department. Less emphasis was placed on the bookkeeping side of its activities with greater emphasis and amplification of its role as a provider of financial and economic advice to the state government. In order to accommodate this shift in emphasis Treasury sought to maximise reform of its management policies and administrative structure. Reform was episodic after the first decade, indeed retarded at times because of the exigencies of war and economic downturn. Success came towards the latter half of the 20th century culminating in an overhaul of old functions and procedures.

The reasons for success were multiple and various: stable government with a firming power base; improving standards of leadership in the major government departments including Treasury; statutory provisions supporting economic management reform; the constant debate surrounding federal–state financial relations; proposals for reform and standardisation of accounting methods in the State’s public service; the professional appointment of qualified or graduate personnel to departments; an Australian Government requirement for greater uniformity in state public accounts; improved education in the theory and practice of public administration; and global economics and associated crises. (On 19 May 1932 the Commonwealth Joint Select Committee of Public Accounts advocated uniform presentation of the public accounts. In 1933 the Australian Government iterated the need for greater uniformity in state public accounts.)

Whatever the agents of change, internal or external to Treasury, they stimulated and gave impetus to the requirement for greater transparency and accountability. This saw more efficient and effective stewardship of the State’s revenue and expenditure.

The first year of the 20th century indicated the necessity for a fresh appraisal of the Treasury’s administrative weaknesses and a want of financial finesse. With political and administrative determination, it could be in the vanguard of reform, indeed a focus on reform.36

In late 1899, a crucial program of reform was buttressed by the then Premier and Colonial Treasurer William Lyne. He urged in the public interest the establishment of a select committee to make full inquiry into the public accounts and report upon the state of the finances of the colony. It was also to report on the differences of opinion arising between the Treasury and the Audit Office and seek the means to resolve incessant disputes between the two. The pivotal and key question for the committee was whether the methodology used for dealing with the state’s finances generally and the Loan Expenditure were adequate.

This 1900 inquiry had its genesis in any number of inducements; a political stratagem to embarrass the previous George Reid government; a genuine attempt to address the perennial problem of Government Accounts; a veiled justification for the raising of extra taxation. Lyne advocated a proper accounting basis which should encourage further overseas capital investors and create a higher credit rating.

Reform was supported in parliamentary debates, a requirement for straightforward bookkeeping, honest exposition of the finances of Parliament and the country. The Committee was appointed on 2 April 1900, the first Commission of Audit carried out by independent Auditors. The Committee of Inquiry was composed of officials from leading banking institutions and accountancy firms. Key Treasury witnesses were called, and (after 43 days of hearings)a General Report was issued on 21 July 1900, with recommendations for specific changes for administrative and economic management reform.

A significant consequence was the passage of the Audit Act 1902. This made provision for the State’s budgeting, accounting and banking arrangements. According to Don Nicholls, a past Deputy Secretary of the Treasury, this was a successful piece of legislation evident from the fact that it remained largely unaltered until replaced in the 1980s by the Public Finance and Audit Act 1983.37 The legislation clearly defined the office, duties and functions of the Auditor-General, vis-a-vis the Treasurer and Treasury.

Another important provision of the Audit Act 1902 was the establishment of the Public Accounts Committee which was required to exercise Parliament’s review powers over the efficiency, effectiveness and accountability of the public sector.38 The fragile relationship and personal rivalry between the two departments was also tempered by the replacement of Auditor-General Edward Rennie by John Vernon on 20 November 1902. Vernon had been Treasury’s Chief Accountant and his approach as Auditor-General was conciliatory as indicated in his first Annual Report. His report was a clear, simple statement indicating the condition of the State’s finances, refraining from captious criticism as to the form or order in which the accounts were compiled by the Treasury.

Three major branches were identified, Administration, Finance and the General Branch. In the interests of economy, the position of Housekeeper, Head Office, was abolished in 1907. The position of Caretaker substituted with an allowance for quarters, fuel and light. It was not until the World War I that women were first employed as shorthand-writers and typists and as the war progressed trialed as junior clerks.

A significant administrative decision was taken in 1911 by the McGowen Ministry. This was the formalising of one of the most powerful and influential financial institutions in this state, the Treasury Insurance Board. This body was established by the Treasurer to supervise the Insurance of Government assets. It was administered by the Treasury Insurance Branch. The Branch formed the nucleus of the Government Insurance Office (GIO) instituted in 1926.

Treasury and World War I

In 1906 Timothy Coghlan, one-time statistician and then New South Wales’ Agent General in Britain, wrote to J. H. Carruthers, Premier and Treasurer:

The Great War demonstrated the growing complexity of financial management and an increasing need for interstate dialogue. Enlistments compromised the effectiveness of advice given by Treasury to the Government. It was not until the epoch of Bertram Stevens, commencing in 1921, that the focus on reform was rehabilitated.

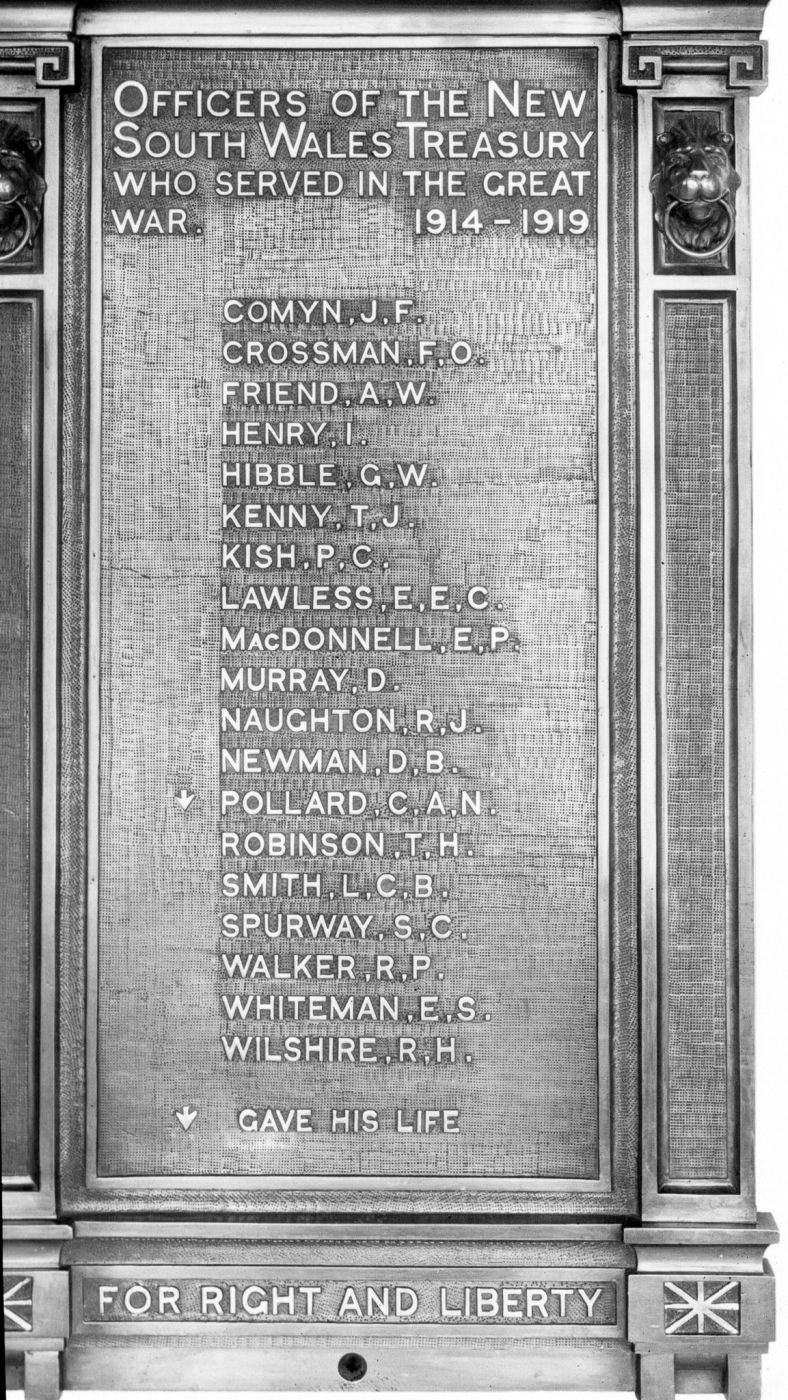

Five Treasury officers, one of whom was killed, had volunteered to fight in the Boer War of 1900. Eighteen enlisted in the Great War, one of whom died. They were all remembered for their sacrifice. This was a conflict which altered significantly the character and spirit of the Treasury of New South Wales.

‘Whither goes thou?’

Michael Lambert, then Secretary of Treasury addressed the Reform Club on 12 July 1996. His paper was titled ‘Whither the Federation’. He observed that ‘in recent times there have been a number of tremors in the Australian Federation which indicate that pressures are building for structural change’. The complications are not new with fresh recognition being extended to the country’s First Nations. The list of complications disturbing federal-state relations in 1996 ‘covered such issues as immigration, health, public housing, education, environment, treaties, guns, etc. Suffice it to say the state of the Federation is not a happy one.’