Request accessible format of this publication.

7. Don’t Mention the War

Author: Brett Bondfield

Hear directly from the author

This chapter provides an overview of the fiscal environment that has evolved around the NSW Treasury since Federation on 1 January 1901.

It takes as its starting point an event that occurred approximately one third of the way along Treasury’s 122 years post Federation. This was the 1942 Commonwealth takeover of the ability of the states to levy income tax. That takeover was complete and included staff, infrastructure and records. Despite an invitation from the Fraser government for the states to re-enter the income taxation space in the 1970s, none, including New South Wales, have done so.

The imposition of uniform taxation under the Commonwealth has been well analysed. Perspectives include, legal, political, financial and the Australian federal compact. This chapter contextualises it over the evolution of the Australian federation as it has impacted the fiscal environment in which the NSW Treasury operates. Treasury had to advise on and adapt to all of the events detailed in this chapter. Like many aspects of Treasury’s work, behind the headline the real story is more complex.

Constitutional background

There are just three short provisions all of which have been in the Australian Constitution from Federation that are relevant to the 1942 Uniform Taxation imbroglio. They are:

Sections 51(ii) & (vi)

Legislative powers of the Parliament

The Parliament shall, subject to this Constitution, have power to make laws for the peace, order, and good government of the Commonwealth with respect to:

(i) taxation; but so as not to discriminate between States or parts of States;

(ii) the naval and military defence of the Commonwealth and of the several States, and the control of the forces to execute and maintain the laws of the Commonwealth;

Section 96

Financial assistance to States

During a period of ten years after the establishment of the Commonwealth and thereafter until the Parliament otherwise provides, the Parliament may grant financial assistance to any State on such terms and conditions as the Parliament thinks fit.

The section 51 powers are not exclusive to the Commonwealth, subject to the very powerful proviso in section 109 (Inconsistency of Laws) that:

When a law of a State is inconsistent with a law of the Commonwealth, the latter shall prevail, and the former shall, to the extent of the inconsistency, be invalid.

The imposition of Commonwealth uniform income taxation, 1942

Under section 51(ii) the Commonwealth power to tax is concurrent with the states. In World War I, the Commonwealth entered the income tax space with a relatively low impost in 1915 as a response to the funding of the war effort. At that time in 1915, all states were levying income tax as was the case in 1942.

The cost of fighting World War II was placing considerable strain on Commonwealth finances. Leading up to the enabling legislation gaining Royal Assent in early June 1942 the war was not going well for Australia. The Japanese had attacked Pearl Harbour on 7 December 1941; Rabaul, in what is now Papua New Guinea, had been taken by the Japanese on 23 January 1942; Singapore had been surrendered on 15 February 1942; Darwin was first bombed on 19 February 1942; and Broome was bombed on 3 March 1942.

To facilitate the efficiency of raising revenue to pursue World War II, the Commonwealth had first requested the states to pass their income taxing powers to it for the duration of the war at the 1941 Premiers’ Conference. The states refused. On 23 February 1942 – two days after the Japanese bombed Darwin – the Australian Government appointed a select Committee on Uniform Taxation to advise it as to the best way taxation revenue could be raised. This committee was so select that the answer was a foregone conclusion. The committee reported to the government on 8 March and its recommendation was released 6 April and recommended the introduction of a uniform taxation scheme throughout the Commonwealth, with the Commonwealth Government as the sole taxing authority for the duration of the war and 12 months thereafter.

The politics of the process was clear from the start with the selection of the three committee members, the prescriptive terms of reference and the very short timetable.1 One of the three members and committee chair, economist R. C. Mills, had been advocating for uniform taxation under the Commonwealth since the 1920s and reportedly considered ‘the claims for state rights as having been lost in 1901 with federation’.2 The states were given one last chance at the 22 April 1942 Premiers’ Conference to reach a compromise and they declined. There had been no support from any state for Commonwealth proposals to take over income tax.3

At that Premiers’ Conference William McKell, Premier and Treasurer of New South Wales, argued that to take away the right to tax was to destroy the right to govern. In a subsequent legal opinion of the Commonwealth this was answered by reference to the defence power and that ‘the suspension during the war of the State’s policy may help to prevent the total and permanent paralysis of the State’s policy and functions and of the State itself’.4 Two things need to be noted here. Firstly, the lasting uniform taxation arrangements were held not to need the defence power to be effective. Second, McKell’s point was political, not legal. That politics came first is evident in another legal opinion from the Australian Attorney-General Herbert Evatt:

On 15 May legislation was introduced into the Australian Parliament, one week after the battle of the Coral Sea. It passed all stages of the Assembly at 4.30 am on 29 May, after 26 hours of sitting. Two days after that, on 31 May, Japanese submarines attacked Sydney Harbour. The Bills passed the Senate on 4 June on the day the Battle of Midway began and shortly before the Battle of El Alamein.

The legislative scheme had four separate but interlocking Acts. The Income Tax Act 1942 (Cth) increased the rate of Commonwealth tax to a gross amount approximately equal to the total income tax revenue of the states and Commonwealth combined. The Income Tax Assessment Act 1942 (Cth) inserted a provision into the Income Tax Assessment Act 1936 (Cth) that gave primacy to the Commonwealth tax by making it an offence for a taxpayer to pay a state income tax debt before a Commonwealth one. Under the Income Tax (War-time-Arrangements) Act 1942 (Cth) the Commonwealth took control of the state revenue departments, including the staff and records. Finally, the States Grants (Income Tax Reimbursement) Act 1942 (Cth) in essence provided a mechanism for the Commonwealth to make section 96 grants to the states to compensate for what they would have recouped if their systems were not taken over, as long as the states did not levy an income tax of their own. The four Acts were assented to on 7 June 1942 and were effective for the year of tax commencing 1 July 1942.

The legal advice provided to the Commonwealth when the Acts were being drafted often came back to discussions of the defence power and its relevance as the support to the elements of the plan.6 Very soon after the Acts were passed, South Australia, Victoria, Queensland and Western Australia commenced a challenge in the High Court. Despite the proposed takeover being dogmatically opposed by McKell,7 New South Wales did not take part. On 23 July 1942, in South Australia v Commonwealth (‘First Uniform Tax case’) the High Court found that the revenue raising arrangements were supported by the taxation power (s 51[ii]) and the revenue distribution arrangements were justified given the extremely broad language of section 96. On 17 November 1942, New South Wales passed the Income Tax Suspension Act 1942 (NSW) which retrospectively ended the imposition of income tax by the State from 30 June 1942. Uniform taxation payable to the Commonwealth has continued to this day.

The practical impact of the four acts was encapsulated in the early remarks of the leading counsel for the states in the 1942 litigation:

The political context of the four acts is equally well encapsulated by the leading counsel for the Commonwealth in 1942:

Of the four Acts it was only the transfer of state staff, resources and records to the Australian Government that needed to be directly supported by the defence power. The transfer was effective on 1 September 1942. The 2010 history of the Australian Taxation Office notes this in the following terms:

The second sentence of this extract would indicate that the victors write history.

At the time of passing the scheme, when asked how long it would be in place, Prime Minister Curtin stated: ‘I am no astrologer and I do not know what history may produce’.11 Then in a Premiers’ Conference in January 1946 the Commonwealth announced its intention to continue the scheme ‘at least for a while’.12

The conflict over financial relations had continued throughout the 1950s, with the Premier of New South Wales, J. J. Cahill, playing a leading part. After the 1956 New South Wales election a Joint Select Committee of the State Parliament was set up to inquire into the operation of the Commonwealth Constitution. In its first report the Committee concluded that uniform tax was ‘a threat to the fundamental structure of the Federal System’ which, if continued, would ‘ultimately destroy it’.13

In 1957, over a decade after the First Uniform Tax case the two most economically powerful states, New South Wales and Victoria, sought to revisit the 1942 case before a differently constituted High Court. This was to no avail. In Victoria v Commonwealth (‘Second Uniform Tax case’) in 1957, the High Court held that the scheme, more accurately, its individual parts, was valid under the section 51(ii) taxation power and the section 96 grants power, except for the provision that gave the Commonwealth primacy in payment.14

This Second Uniform Tax case confirmed why using the grants power in section 96 on the terms it did was a valid exercise of the Commonwealth power. Chief Justice Dixon’s overview was that:

Chief Justice Latham in the First Uniform Tax case set out the rationale for how it operated in the following terms:

The Australian Government takeover of the income tax space deprived the NSW Treasury of a significant revenue source. Even though the grants provided to the states matched the lost income tax revenues this re-established a substantial level of vertical fiscal imbalance in the federation. In the year ending 30 June 1941 income taxation represented 67.8 per cent of the State’s tax revenue, which was second highest to Queensland at 68.1 per cent, with the average across the states being 63 per cent,17 albeit with the Commonwealth’s undertaking to reimburse it for the revenue forgone.

However, the wide powers given to the Commonwealth to decide how New South Wales and the other states spent what was now the Commonwealth’s money would change the fundamental dynamics of revenue for New South Wales and in so doing threaten State autonomy. This was overtly acknowledged in the First Uniform Tax case and that dealing with this threat was a matter for politics.18

Spending time on the taxation events of 1942 is instructive. Firstly, finance in the Federation is and always was highly political. Here we see the politics played out in the context of World War II. The preceding discussion references the stages of the war to make the point of how dire the national position was. Secondly, the Constitution and its interpretation by the High Court are the ‘rules’ by which fiscal politics are played. The Australian Government has proved adept at using those rules to its political benefit. In 1942, state laws were never overridden. Rather, the states vacated the taxation field being ‘induced’ rather ‘tempted’ by the availability of compensatory grants from the Commonwealth.

It should also be noted that New South Wales and the other economically powerful states were only briefly independent of needing Commonwealth financial support to undertake their basic activities. Levying income tax was a path to that independence and it dead-ended one third though Federation. Since 1942 there have been two paths for NSW Treasury to navigate to fund New South Wales. The very public path of direct revenue raising is getting narrower and more treacherous. The other path is negotiating with the Australian Government and the other states for a fair share of the revenue collected by the Commonwealth and that predates 1942. In fact, it was pivotal in the negotiations to federate.

A review of the literature indicates that the power to levy concurrent taxation was not contentious.19 That raises the question: Why?

At the time of Federation, New South Wales had an income tax in place since 1895. The tortuous path to this commenced in 1886 and success required a very significant expenditure of political capital in the face of fierce sectorial opposition20 (a feature of all colonial and State first forays into income taxation). The only colonies not to have an income tax at Federation were Western Australia and Queensland, which started levying theirs in the financial years of 1908 and 1903 respectively.21 The soon-to-be Commonwealth did not have an income tax until World War I22 and in introducing it said it would ‘not tax heavily, or more than necessary’.23

Following Federation, reliance by the states on income tax for revenue ‘increased ramatically’.24 As states had retained income tax as a source of revenue, transfers from the Commonwealth were less important over time.25 Although income tax was the principal method by which New South Wales collected funds for general public services it was not the only source of revenue. ‘Other sources were stamp duties, death duties, betting tax, and licences to sell liquor as well as the profit made in the conduct of the State Lottery, all under the administration of Treasury.’26

It was recognised that the interfaces between the seven taxation systems and their administration was complex and since 1915 involved all Australians dealing with at least two taxing authorities (the Commonwealth and at least one state).27 This was recognised as a problem and by 1937 two Royal Commissions and a series of conferences of state and federal tax officials had resulted in some nationwide uniformity and anomalies being removed for the assessment of income tax.28 A uniform income tax Act – the Income Tax Assessment Act 1936 (Cth) – was adopted nationally and applied for both state and federal tax assessments from 1936–1937. According to Smith ‘the 1937 nationwide adoption of this Act was the most significant result of the search for tax harmony in the interwar period’.29 Concurrent income taxation comes to an end just four years from this.

Taxation was not seen as the preeminent revenue raising tool. Customs and excise duties (taxes) on the sale and importation of goods were the main revenue sources of the Colonies at the time of Federation. They had been for a long time before that. Moreover, the current wisdom was that customs and excise would remain so into the future.30

Economically, Federation was to create a single market in Australia,31 and to do so the Commonwealth was given exclusive power over customs and excise by section 90 of the Constitution. In the first 10 years of Federation customs and excise made up 100 per cent of Commonwealth revenue.32 This meant the soon-to-be states gave away their main revenue generator.33 Customs and excise is estimated to have comprised three-quarters of total colonial taxation revenue at Federation34 and that taxation revenue made up about half the total revenue of the colonies. Thus the colonies’ attention turned to how that was going to be returned to them in the near and long terms. But it could ‘hardly be doubted that the treasurers of the day saw the Commonwealth largely as an agent for the states, not even an equal partner. Moreover, it was to be an economical agent’.35

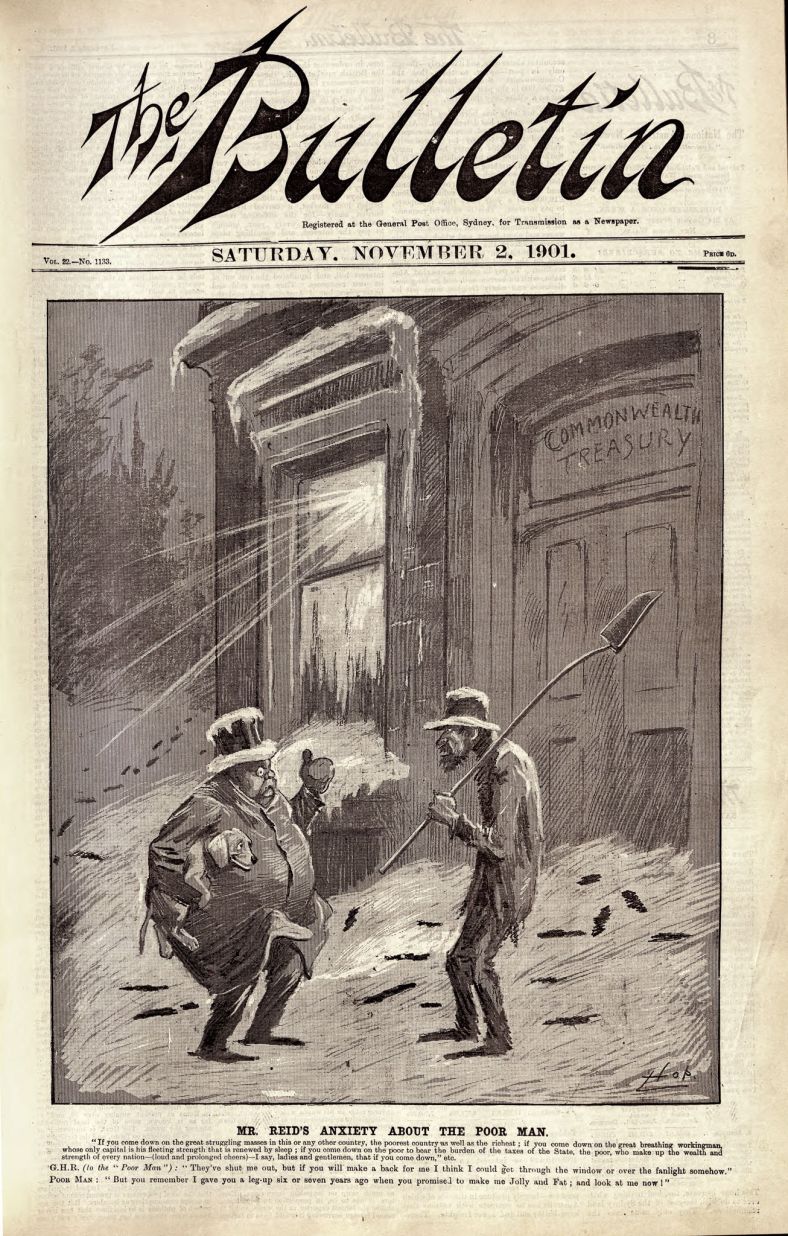

NSW Premier and Treasurer George Reid, one of the Fathers of Federation, was a vocal force in this matter. Reid fought hard for the best financial outcome for New South Wales36 as he engaged with politics, both those of New South Wales and Federation, as voting for the Federation went down to the wire.37 Reid got his nickname ‘Yes No’ Reid by saying he would vote for the draft while recommending the citizens of the Colony vote against it ‘particularly its financial dangers to the interests of New South Wales’.38 The first vote in New South Wales reached a majority in favour of federating but did not pass a second hurdle of number in favour. Finally, a set of words in the draft Constitution and the mathematics of how the revenue was to be returned was agreed. New South Wales voted a second time and adopted the draft Constitution.

The Constitution contained section 87, the ‘Braddon Clause’ – Braddon was the Premier of Tasmania – with a sunset of 10 years.39 Section 87 required the Commonwealth to return three quarters of the customs and excise revenue to the states for 10 years. In part, it was the 10-year sunset that can be argued gave rise to section 96 and the express power of the Commonwealth to make grants to the states.40 This section was included towards the very end of the Constitutional negotiations and was not directly linked to the sunset clause in section 87 and the reasons for its inclusion were not clearly articulated at the time.41

In an era where leaders could ‘hardly conceive that customs might not forever be the principal source of government revenue’, a mechanism for states to get part of the exclusive customs and excise take was a factor to be considered.42 In a mark of how the fiscal world of 2024 was not foreseen at Federation, in the year before the introduction of the Goods and Services Tax on 1 July 2000, customs and excise duties made up just 11.6 per cent of Commonwealth taxation revenue.43

From the outset the revenue distribution model was suboptimal. The loss of an

ability to levy duties on customs and exercise necessitated regular transfers from the Commonwealth. The words of Alfred Deakin ring as true in 2024 as they did in 1902 – the constitutional settlement left the states ‘legally free, but financially bound to the chariot wheels of the central government’.44 It is only that those bindings were reinvented in 1942.

Before the first 10 years ran out the Commonwealth overcame a constitutional requirement in section 94 that it redistribute surplus revenue to the states. The Commonwealth allocated unspent monies to ‘funds’, basically accounting provisions, that carried over to the next financial period. When this was challenged by New South Wales in 1908 the High Court held that this was valid, and the funds set aside were not surplus.45 This is an early indication of how the fiscal tensions between the states and the Commonwealth are worked through and ultimately decided by reference to the Constitution and the High Court as umpire.46 Though courts should be a last resort ‘because of the inherent untidiness of a Federal system of government’.47

Another way of raising funds is to borrow. Writing in 1994, a prominent constitutional scholar pointed to the financial dependence of the states on the Commonwealth as founded on the ‘twin rocks of the 1929 financial depression and World War II’. The Great Depression entrenched the states’ reliance on the Loan Council for raising debt finance. Basically, they surrendered their capacity to borrow on the international capital market.48 This also provided for the Commonwealth to be able to take over state debts. This was supported by a 1928 constitutional amendment (inserting section 105A).

Under this political compromise the states would not go to market (usually London) to raise debt finance directly. Rather, the Commonwealth would do it on their behalf. This Financial Agreement was approved in Financial Agreement Act 1928 (Cth) and reciprocal State acts. This remained in place for 58 years. The Loan Council considered the borrowing programs of all parties, except the Commonwealth as regards defence expenditure.49 In effect the Commonwealth borrowed on behalf of the states and there was a ‘democratic’ forum that determined how much. Each state had one vote and the Commonwealth presided with two votes and a casting vote.

Commensurate with the loss of New South Wales’ borrowing autonomy, its Treasury needed to direct energy towards developing cases to be presented to all the other governments and to defending them at the Loan Council. There was also a darker side to section 105A as far as New South Wales was concerned. It ensured any agreement was obligatory on the Commonwealth and states, and beyond the control of any law of any of the seven parliaments.

Under Premier and Treasurer Jack Lang, New South Wales sought to default on payments of interest on loans taken out on its behalf by the Commonwealth. Like a bank taking debt recovery action, the assets of New South Wales were garnisheed. Carew details the practicalities (some are quite colourful, involving cash in car boots) of how NSW Treasury sought to have the State work under this impost.50 In the end the High Court held that the Commonwealth could pass a law garnisheeing the revenues of New South Wales to satisfy amounts the Commonwealth claimed it owed for interest due under the Financial Agreement.51 That law52 was held valid and in effect overrode the New South Wales Constitution.53

There was only a very short period post Federation where New South Wales had sufficient financial autonomy not to be the significantly weaker negotiating partner

of the Commonwealth, if it needed Federal support at all. After 1942, vertical fiscal imbalance was entrenched with New South Wales as service provider, reliant on the Commonwealth as revenue earner, for the funds to provide those services such as health, education and public order. On top of that the way uniform taxation was achieved, using the grants power in section 96, made it clear that the Commonwealth had the power to dictate how those funds were spent.

The present day: raising revenue directly and negotiating financial support

Australia’s first Prime Minister, Edmund Barton, assured the states that the Australian Government would leave the direct tax territory to them:

That promise evaporated 41 years later. The current NSW Treasury has to raise funds by a mix of means that was not envisaged at Federation. New South Wales and the other states have not levied income tax since the introduction of the uniform tax scheme, despite a decade long window opened by the Fraser government in Canberra when it passed the Income Tax (Arrangement with the States) Act 1978 (Cth). In a stated attempt to narrow the federal/state fiscal divide, a state which met the requirements of the Act, including the adoption of the bases of assessment for federal income tax, could impose an income tax surcharge (or grant a rebate) which would be collected or administered by the Commonwealth. That Act was repealed by the Keating Government with the Income Tax (Arrangements with the States) Repeal Act 1989 (Cth). It has been said that this repeal was to prevent the states from threatening ‘the Commonwealth’s monopoly control in the field of income tax, and its policy of forcing restrictions on state expenditure’.55

There is another side to the lack of state appetite to re-enter the income tax space. States benefit under uniform taxation because the political opprobrium is shifted to the Commonwealth and the states have ‘a much simpler and more pleasant alternative, by applying to the Commonwealth Government for an increase in their annual grants under s[ection] 96’.56

Before discussing the current make-up of the New South Wales revenue, the final major change in the federal/state financial landscape needs to be briefly acknowledged, being the introduction and operation of a broad-based Commonwealth consumption tax, the Goods and Services Tax (GST) on 1 July 2000.57 Prior to the GST there was a wholesale sales tax introduced by the Commonwealth in 1930, which was a broader-based consumption tax beyond customs and excise duties.58

The GST is not a state tax. The Commonwealth levies and collects it with GST revenue less administration costs paid to the states. The formula to distribute the funds is determined by the Commonwealth Grants Commission which makes recommendations to the Commonwealth on how to distribute the funds. It is not as simple as New South Wales being automatically paid the GST generated by transactions in its jurisdiction. There is an intergovernmental agreement that underpins the revenue distribution between the states along with the Grants Commission’s inputs. Both have required and will continue to require input from the NSW Treasury.

In 2020, NSW Treasury released a report, NSW Review of Federal Financial Relations.59 It calculated that while states delivered almost half of all government operating expenditure, the Commonwealth raised more than 80 per cent of the tax revenue and provided almost 45 per cent of state revenues.60 Since the publication of that report these percentages have not significantly changed.61

According to the 2020 report the GST is the largest single revenue source for the states, having raised $66.4 billion in 2018-19 and provided 22 per cent of revenue in New South Wales. This is similar to the combined value of the two most significant state taxes: transfer duty (principally on real estate sales) and payroll tax.62 Based on 2021-22 financial year figures, the GST raised an estimated total of $74.2 billion.63 The most current figures from 2021-22 show NSW GST receipts of $23.3 billion,64 which is approximately equal to transfer duty and payroll tax combined at $23.4 billion.65 Based on the most recent figures, the GST remains the single largest New South Wales revenue item at 22.5 per cent of total revenue in 2021-22. However, there are other specific Commonwealth grants that when added to the GST total $44.9 billion and account for 43 per cent of New South Wales revenue.66

In 2021-22 taxation revenue from NSW taxes was $39 billion and comprised 38 per cent of total revenue which is less than total Commonwealth grant revenue.67 Here it is important to note that the NSW tax revenue was comprised of 22 enumerated taxes and three categories of ‘other’ taxes.68

Concerns have been expressed over the robustness of the tax base of New South Wales and state tax bases more generally.69 There are two reasons that make elements of the NSW tax base fragile. One is interstate competition. For example, a state looking to increase employment opportunities may make itself more attractive for employers, by having lower payroll tax rates. This can cause a race to the bottom and a ‘hollowing out’ of that revenue source.70 In the past it has even led to a nationwide exit from a field of taxation. This happened when Queensland abolished death duties/inheritance taxation in 1977, causing a domino effect and by the early 1980s no death duties were imposed by any state or the Commonwealth.71

The other fragility is that of the spectre of section 90 of the Constitution that gave customs and excise exclusively to the Commonwealth at Federation. The issue this creates is that when a state tax (like a licence fee) is calculated by reference to business turnover, (for example alcohol sales in a liquor licence fee) how closely does it need to be tied to that turnover to be determined an excise duty? In 1997 that question was answered by the High Court with New South Wales tobacco franchise fees held to be excise and thus invalid due to section 90 of the Constitution.72 The Commonwealth stepped in and legislated for the collection of these types of imposts and redistributed them to the states and territories. The then-NSW Treasurer Michael Egan was reported as saying that: ‘The Commonwealth doesn’t have to abolish the states; it just lets them wither on the vine.’ As a result of that case the 1997-98 NSW Budget outcome was revised down from a forecast surplus of $26 million to a $300 million deficit.73

An October 2023 High Court case from Victoria74 has made the position of New South Wales and all other states more precarious. This case involved the registered operator of a zero or low emissions vehicle paying a charge for its use on public roads, levied on the basis of distance travelled. By majority the High Court held it was an excise, a tax on goods, not a tax on an activity. The dissenting minority said the reasoning of the majority had the potential to greatly expand the scope of section 90 and could take away from the states the ability to levy duties paid on: the transfer of goods that were transferred with land or businesses; motor vehicle duties and vehicle registration charges; commercial passenger vehicle levies; gaming machine levies and ‘point of consumption’ betting taxes; waste disposal levies; and tobacco licensing fees.75

If this were to be the outcome of the case the Commonwealth could impose taxes to mirror what the states lost. But that would be complicated due to the requirement not to discriminate between the states. It would also be another point for negotiation between a fiscally stronger Commonwealth and weakened states.

Sometimes federal fiscal centralisation is relaxed – such as in the early 1980s, when states were able to return to the money markets to raise their own funds. In New South Wales, the entity created to do this is TCorp, established under legislation enacted in 1983. TCorp is a wholly owned entity of the State and is part of the New South Wales Treasury cluster. It is the central borrowing authority of New South Wales, with a balance sheet of $158 billion and $107 billion worth of assets under management. In 2021-22, it generated a dividend of $95 million paid to the NSW Government.76

Commonwealth grants to the states are made under the Federal Financial Relations system.77 It includes Commonwealth-State funding agreements for government services that are jointly funded and GST revenue-sharing arrangements. New South Wales, like the other states, relies on the Commonwealth to fund essential services through two primary channels: the GST, which is untied, and tied funding agreements, earmarked for specific areas of service delivery.78 They are ‘tied’ because the Commonwealth, after negotiation, specifies the terms under which the grant will be made and reporting obligations. In 2021-22, 47 per cent of Commonwealth grants to New South Wales were tied.79 These require resource intensive negotiation and reporting led by NSW Treasury.80 Its 2020 Report describes the environment of those negotiations as:

At that time, New South Wales was party to around 50 Commonwealth funding agreements82 and is currently party to 56.83

Conclusion

The way uniform taxation under the Commonwealth was achieved in 1942 made it clear that the Commonwealth has few restrictions on how it distributes its money to the states. That uniform taxation, now supplemented by the GST, gives the Commonwealth 80 per cent of all the taxation revenue raised in Australia and means it has a lot of money to distribute. The states deliver many services and need to negotiate for their fair share of that money. That is a political endeavour, supported and sometimes led by NSW Treasury. That was also the case at Federation, with the addition of a specific distribution rule placed in the Constitution that was effective for the first 10 years.

A powerful tool in the Constitution to provide for fiscal autonomy for the states was terminated on 30 June 1942 when the states stopped levying income taxation. The possibility for this to happen was not foreseen at Federation, how could it have been? More importantly the unforeseen impact of the Constitution on the ways left for states to independently raise revenue in lieu of income taxation is playing out now.