Request accessible format of this publication.

Introduction

Author: Paul Ashton

Hear directly from the author

In the foreword to Golden Heritage, written for NSW Treasury’s 175th anniversary, Michael Egan, the 57th Treasurer of the State, wrote:

Golden Heritage outlines the institutional evolution of the State’s most powerful department with appendices of Treasurers (57 at the time, now 67), Secretaries (then 23, now 29) and staff dating back to 1824. Today, Treasury’s staff includes almost 800 analysts, economists, policy advisors and subject matter experts. Women today represent more than half of Treasury staff, but their presence was marginal until the latter half of the twentieth century.2

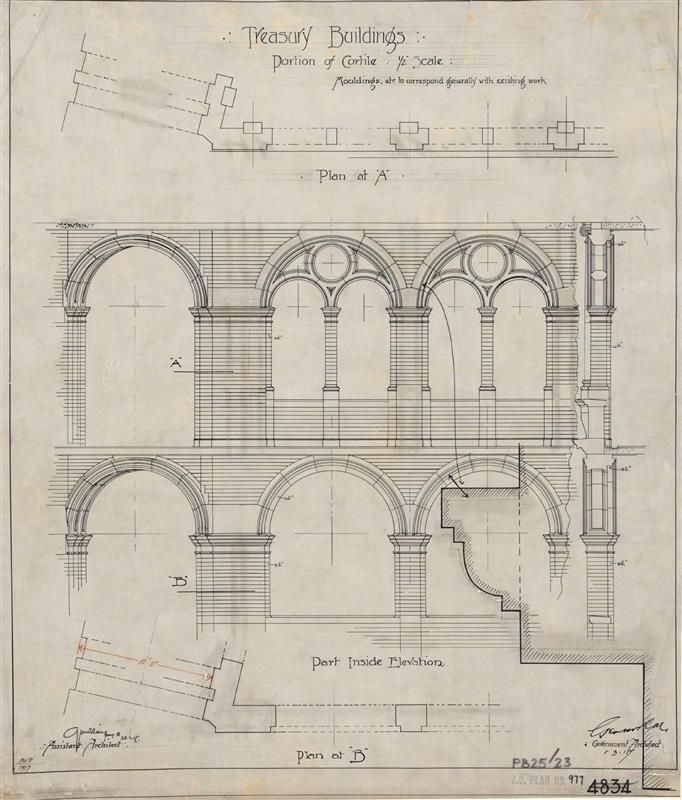

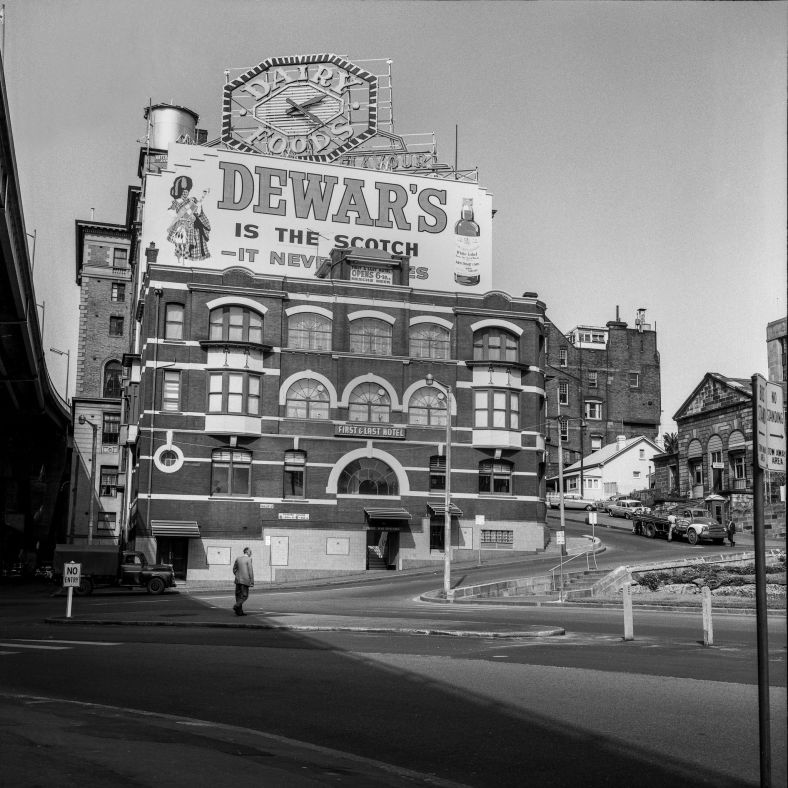

The buildings in which the Treasury was housed over time is also covered. It was intended to be, as it is, a useful resource for historians, researchers, parliamentarians, public servants and genealogists with a thirst for this aspect of the Government’s past. So, too, is Roberta Carew’s meticulously researched thesis on NSW Treasury’s history to 1976.3

Together these histories show the evolution of NSW Treasury from mere colonial accountant to the preeminent department of the State which today, as the Treasury notes in its 2022–23 Annual Report,

They demonstrate the ‘sustained and concentrated focus on economic and budget reform’ which, in particular, characterised the Treasury’s 20th-century history.5 And they have involved working closely with the then-Office of Climate Change (now spun off from Treasury and part of the Department of Climate Change, Energy, the Environment and Water) and the NSW Productivity and Equality Commission to ‘contribute to research and discussion papers that explore economic, regulatory and service delivery reform opportunities.’6 But they also indicate a shift from policy maker to facilitator.

As noted in Golden Heritage, the establishment of the Treasury’s Budget Branch in 1946, part of the process of post-war reconstruction, saw Treasury take on a key role in ‘helping form policy in New South Wales’.7 A watershed in this story was the establishment of NSW Treasury Corporation (TCorp) on 10 June 1983 as the central financing authority for the State’s public sector. Its broad range of financial services includes: borrowing from domestic and international sources; running a term deposit service to invest surplus public funds; managing ‘Hour-Glass Investment Facilities’ for measuring the performance of public agencies; providing economic analysis, debt management and advice on structured finance transactions; and delivering the system of NSW Treasury Bonds to allow direct public investment.8 This reflected an important new context: the corporatisation of government.

Historians, journalists and other writers have seen the 1980s in various lights. Frank Bongiorno, Professor of History at the Australian National University and a contributor to this book, has noted that:

These were all key contexts for the Treasury’s history in earlier times. But they were all ‘broken by the end of the 1980s’. Some of them, however – such as White Australia and paternalism – linger today, evident in ongoing moves towards Reconciliation with Indigenous people.

Bongiorno went on to note that another journalist, George Megalogenis – a leading political and economic writer:

Whatever one’s perspective, this was a time of change and, politically, a time of ‘crash or crash through’. New South Wales – and Australia – crashed through. And NSW Treasury played a major role in this.

For First Nations people in New South Wales, the early 1980s saw a landmark event take place. After years of Indigenous advocacy, activism and protest, academic interventions and reports and inquiries – most notably the 1978 NSW Parliamentary Inquiry into Land Rights, chaired by Maurie Keane – the NSW Aboriginal Land Rights Act was passed in parliament on 4 May 1983. The Act established the NSW Aboriginal Land Council (NSWALC).10

NSWALC Chairman Craig Cromelin noted in a eulogy to Maurie Kean – Member for Woronora who chaired the NSW Government’s 1978 ‘groundbreaking committee that recommended Land Rights’ – and former Prime Minister Gough Whitlam, both of whom passed away in October 2014, that:

This resulted in the establishment of the NSW Legislative Assembly’s ‘Select Committee Upon Aborigines’. Taking a fresh approach which eschewed assimilationist ideas, the committee produced two significant reports in 1980. The comprehensive recommendations in its main report:

The initial working of the Aboriginal Land Rights Act 1983 was by no means smooth. For six months after September 1985, for example, ‘funds from the State Treasury were frozen to [the] NSWALC. This … was held by Treasury during negotiations over amendments to the ACT.’13 Nevertheless, perhaps the most critical part of the legislation remained unchanged and unchallenged. Under Part 3 of the Act, the NSWALC received 7.5 per cent of all land tax revenue until 1998. These funds were to be used to ‘acquire, manage and develop land to meet the social, spiritual and economic needs of the Aboriginal people of NSW.’14 Today the Council has assets in excess of $500 million.15

This bicentennial volume on aspects of NSW Treasury’s history charts the shifts – sometimes slow, sometimes more seismic – of its management of the State’s public economy. It is, however, different from the earlier histories. It takes a ‘slice’ approach, looking at events, people and historical processes that the Treasury has been involved in to varying degrees and contributed to shaping New South Wales’ broader cultural, economic, environmental and social history. It is also made at a time when ‘truth telling’ is critical to responsible government. This history is part of the Treasury’s commitment, as noted on its website, to continue:

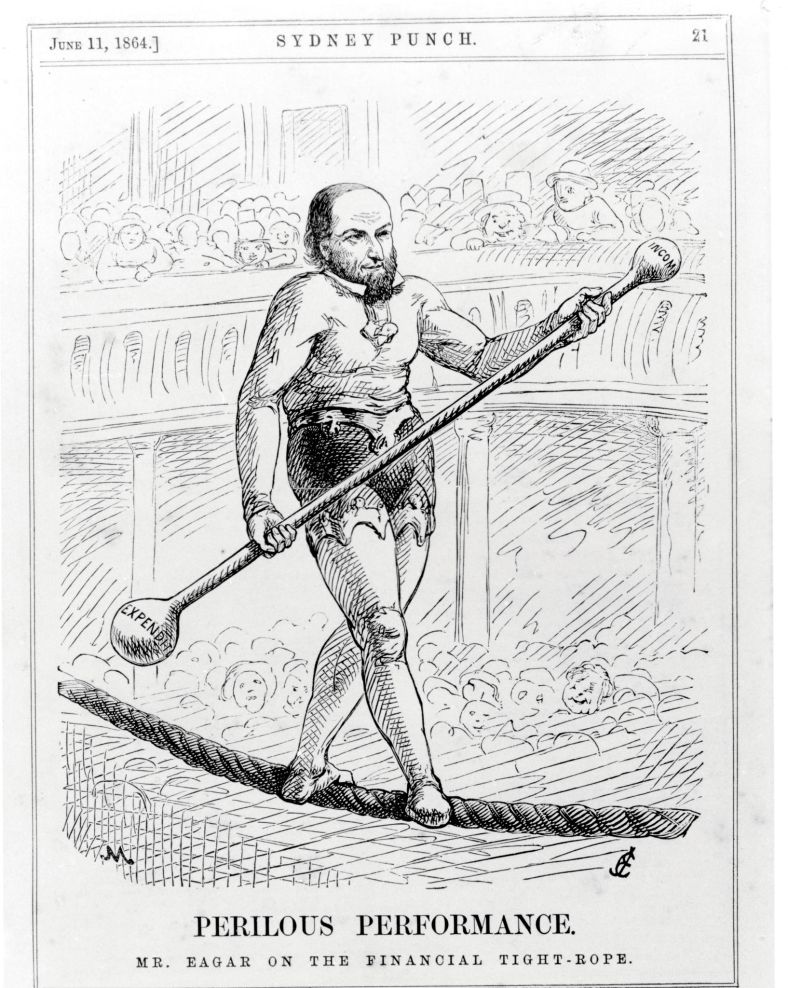

Thus, as suggested in its main title – Walking a Tightrope – this book is something of a balancing act..

Michael Egan’s assessment of public perceptions of NSW Treasury reflects the at times difficult positions in which it has found itself. In 2003, political cartoonist Alan Moir produced a cartoon for the Sydney Morning Herald satirising the Treasury’s relationship with the gaming industry, and poker machines in particular. Amendments to legislation around gambling, including a requirement for gaming machines in the State to adhere to the national standard, had stirred up significant public debate over problem gambling.17 One bind for the Treasury was that at that time around 9 per cent of tax revenue and 3.3 per cent of total State revenue was generated by taxes on gambling profits.18 But some argued that gambling is a popular Australian pastime with a long and deep history in Australian culture.19 In 2023, negotiations with the Star and Crown Casinos over casino tax proposals were to occupy a significant portion of new Labor Treasurer Daniel Mookhey’s time.20

This situation can be traced back to the way in which the Australian Constitution configured the federation of six squabbling colonies. Just before Federation in 1901, The Bulletin, the highly influential Sydney-based magazine, feared that New South Wales ‘had conceded too much in terms of financial and political sovereignty’.21 Today, under federal arrangements, the State has limited options for raising revenue through taxes. These include land taxes, payroll taxes, stamp duties, mineral royalties (technically not a tax), passenger service levies, health insurance levies and gaming and wagering taxes. This is a significant part of NSW Treasury’s history: its ongoing relationship with the Australian Government and the national Treasury. But that’s another story.

Milestones and moments

The chapters presented in this book provide windows into the Treasury’s complex story. They flow, more or less, chronologically. And they are divided here into two parts, Milestones and Moments: larger milestone events or processes, and moments that have connections to NSW Treasury. But the story starts well before 1824 when the Treasury was formally established.

Milestones

In their chapter Paul Irish and Michael Bennett examine the nature of the Aboriginal economies pre-invasion and post-invasion. It demonstrates that Aboriginal people adapted their economies to deal with new colonial realities, drawing on their knowledge and connection to Country.

Carol Liston explores the colonial economy prior to and after the establishment of the Colonial Treasury which was triggered by the Bigge Report into the management of the prison settlement in New South Wales. It demonstrates how the colony remained part ‘of an empire tied by paper – instructions, reports, legislation – to its metropolitan heart’. New South Wales changed from British sterling to Spanish dollars as currency in the mid-1820s. This created accounting and political issues for a time. The first Colonial Treasurer had to deal with this, as well as the emergence of private banks in the late 1820s that then collapsed in the depression of the 1840s. Political in-fighting involving the Colonial Treasurer was part of the concerns when Governor Bourke resigned at the beginning of 1837. The economic and administrative issues with the British Government as the real Treasury effectively lasted until the gold rushes and self-government.

Christopher Lloyd looks at the enormous transformation that the gold rushes made to the economy and administration of New South Wales. This was a peaceful transformation the enormous scale of which was rarely seen elsewhere in the 19th and 20th centuries. The most significant effects came from the massive influx of people, doubling the population within a decade, and the large increase in private wealth. (Victoria experienced an even bigger demographic shock.) By the mid-1850s, the Sydney Mint was producing gold coins to facilitate the colonial economy and the colony’s movement to responsible government was achieved, largely attributable to the gold and the population boom. With responsible government came financial independence so that NSW Treasury at last had sufficient revenue from the crown land sales and other sources to fund the huge infrastructure needed for a greatly increased economy and population.

Garry Wotherspoon assesses the impact of the colonial Treasury’s post-gold rush belief that the Government should play a major role in promoting economic growth, mainly by the judicious construction of public works and a carefully devised fiscal policy. And for a colony keen to open up usable land and export the products of the colonists’ labours, railways were the way to overcome ‘the tyranny of distance’. Railways, as Garry notes, were epochally important in colonial history. The ‘iron horse’ represented a new wave of the colonisation of Aboriginal lands, though Aboriginal people had a complex relationship with railways. For the Treasury, there were concerns about the riverboat trade on the Murray and Darling Rivers, shifting taxable goods to Melbourne or Adelaide. On the plus side, the security of rail construction using British rolling stock allowed New South Wales ongoing access to the London capital market.

Roberta Carew delivers a more institutional contribution which examines Treasury’s role in the moves towards federation, its administrative evolution – including the rise of the modern public service – and Treasury’s post-federation history until World War I. This is followed by Peter Hobbins’ treatment of the significant fiscal and political changes that marked Federal-State relations in the decade after the Constitutional ‘Braddon clause’ expired in 1911. With the nascent Federal Government now entitled to an expanded revenue base from the states, its powers grew in relation to continental concerns such as defence, quarantine and interstate trade. At the same time, citizens came to expect far greater government investment in their welfare, especially via pensions, hospitals and public health. In New South Wales, the changing social contract and shifting intergovernmental relations were foregrounded via several major crises that characterised the 1910s. Three case studies are considered: the 1913–14 smallpox epidemic in Sydney, the Great War of 1914–18 and the pneumonic influenza pandemic that followed over 1918–19. The impact of NSW Treasury decisions through each of these emergencies is explored at the level of individuals, communities, institutions, the state and the nation.

Brett Bondfield discusses Federal–State fiscal relations during World War II. Finance needs during the war saw Commonwealth tax increases, and the Australian Government asked the states to vacate income tax – which they refused to do. In 1942, a Committee on Uniform Taxation was established. It recommended uniform income tax at the federal level. After negotiations with the states failed, the Australian Government enforced an income tax takeover by acting unilaterally with legislation in May 1942. This effectively forced the states out of income tax, thus reconfiguring Federal–State financial relations. An immediate constitutional challenge by some of the states was unsuccessful in 1942. Federal–State fiscal relations would never be the same.

Moments

Perhaps one of the most significant moments in the Treasury’s past saw the only dismissal of a Premier in Australia’s history. Frank Bongiorno writes about Labor Premier Jack Lang’s announcement of the ‘Lang Plan’ in February 1931 around the height of the Great Depression. It entailed a temporary cessation of interest repayments on debts to Britain and the reduction of interest on all government borrowings to 3 per cent to free up money to stimulate the economy.

Treasury also had connections to ‘high’ and ‘low’ culture – from gambling, as we have seen, to ‘Don Giovanni’. The original cost estimate to build Sydney Opera House was $7 million. The final cost, as Minna Muhlen-Schulte writes in her chapter, was $102 million. It was largely paid for by a state lottery initiated by the Treasury and conducted between 1958 and 1986.

On 14 February 1966, Australia began the official transition to decimal currency. As Kylie Andrews observes in her chapter, this was a pivotal point in the nation’s history. C-Day – or ‘Changeover Day’ – signified how the nation was increasingly reshaping its cultural, political and economic identity. The remarkably smooth adoption of dollars and cents demonstrated Australia’s eagerness to embrace a philosophy of ‘out with the old and in with the new’. Manifesting fundamental shifts in Australia’s status within the British Empire/Commonwealth in the post-war years, the nation’s social and economic systems and cultures were transforming rapidly. This chapter highlights how State and federal legislators worked cohesively to overcome the weighty task of implementing change, NSW Treasury working in partnership, and largely behind the scenes, with federal counterparts in the broader national roll-out.

Peter Spearritt and Anne Gilmore continues Garry Wotherspoon’s story of government investment in public transport. It charts many moments: the massive expansion of the Sydney railway system in the interwar years, including the Harbour Bridge, the underground railway and the electrification of suburban lines. Both the Railway Commissioners and the Public Works Department had ample funding, with loan funds facilitated by the Treasury. By the late 1950s, highways and later urban freeways started to get Commonwealth funding, at a time when the states, having lost the income tax power during the war, had little money to invest in public transport. The large tramway systems in Sydney and Newcastle were abandoned to save money and replaced by buses. In the corporatisation era toll roads, the airport railway and the Harbour Tunnel were funded as public private partnerships. Facing massive congestion in a city of five million, the state government is augmenting its railway network and reintroducing trams. These, along with the rise of electric cars, are part of the Treasury’s role in promoting a low-cost, clean-energy economy.

Marilyn Hoey and Nina Giblinwright look at the Aboriginal trust repayment scheme (2005 to 2011). It asks: has the NSW Government addressed the issues of human rights abuses of past government policies affecting the Indigenous people of New South Wales? It concludes that within the legal and political framework set by the Government, the Scheme did successfully meet many of the elements of international human rights reparations. But not all of them.

Early this century, rights of people with disabilities were recognised in abundant rhetoric. ‘Person-centred planning’, Matthew Richardson and Patrick Keyzer write in their chapter, 'was official policy'. But thanks to calamitous underfunding, conditions were grim for people dependent on state disability services. This chapter tells the story of visionary administrators, politicians and activists who teamed up in a time of distress to turn New South Wales around – from an example of privation to world leading progress. Treasury’s recognition of modelling which proved disability spending would have to outpace revenue growth opened the way for the revolutionary Stronger Together programs (2006, 2011) and eventually the National Disability Insurance Scheme (NDIS).

Peter Read reviews the origin of the Reconciliation policy and how NSW Treasury has adapted its principles to its own Reconciliation Action Plans. Yet the principles and practices of Reconciliation have been challenged in the past decade by the Indigenous leadership. Where does that leave the initiatives and successes of the past decades? Where to now?