Request accessible format of this publication.

12. The Aboriginal Trust Fund Repayment Scheme, 2005-11

Authors: Marilyn Hoey and Nina Giblinwright

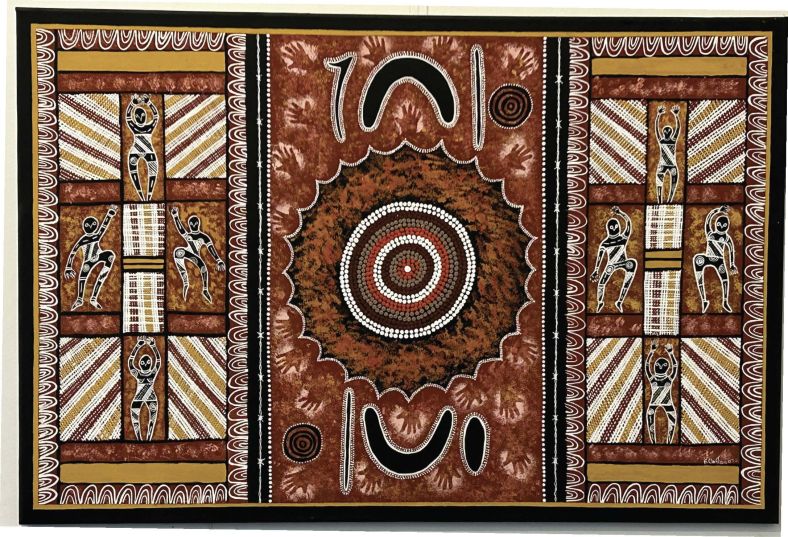

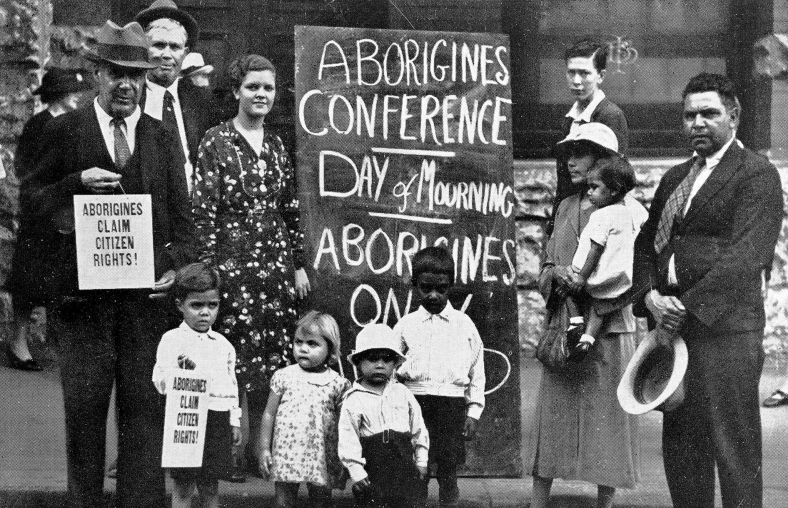

More information on this image can be found at the end of this page at Image notes: First Aboriginal Day of Mourning

(Courtesy Faye Clayton-Moseley)

Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander readers are advised that this chapter contains historical images of Aboriginal people and places of cultural significance and descriptions of historical mistreatment. We have also retained some historical terminology that may today be considered offensive, but which we feel is important to convey sentiments at the time. Reader discretion is advised.

At the beginning of the 21st century, many Australians were shocked to learn that state governments still held monies taken from Indigenous people more than half a century earlier.

This chapter examines the NSW Government’s attempt to right this injustice. It evaluates the work of the NSW Aboriginal Trust Fund Repayment Scheme (the Scheme), its role in Indigenous reparations and, to some extent, the role of NSW Treasury in the economic and political policies relating to Indigenous people and communities.

In December 2004, the NSW Government committed to repaying the Aboriginal Trust Funds (the Funds) to Indigenous people and their descendents.1 The Aborigines Protection Board (APB) and Aborigines Welfare Board (AWB) (the Boards) managed the Funds and supported the ideology of assimilating Indigenous peoples and cultures into the settler colonial nation.2

The Scheme is evaluated within the framework of human rights reparations theory, focusing on the United Nations Basic Principles, which identify three rights for victims: access to justice, adequate reparation, and access to information.3 Reparations might involve compensation, satisfaction or how victims are treated.4 Ultimately, the Scheme met many elements of human rights reparations but failed to adequately address the broader need for just collective reparations.5

More information on this image can be found at the end of this page at Image notes: First Aboriginal Day of Mourning.

Background

The Aborigines Protection Act 1909 (NSW) and its later amendments gave both the Boards (the APB and AWB) immense control over all aspects of the lives of Indigenous people. The Act allowed the Boards to control family endowment payments to Indigenous families, indenture Indigenous youths into domestic service and apprenticeships, determine their pay and conditions, and require employers to submit all wages to the Board except pocket money.

There is extensive contemporary research that views the position of Indigenous people under the Boards as ‘modern-day slavery’, a definition covering a variety of situations in which a person is forcibly or subtly controlled by an individual or a group for the purpose of exploitation.6 In research on Indigenous workers, Curthoys and Moore noted that the word ‘slave’ is often used rhetorically, metaphorically or simply carelessly, on the tacit assumption of a simple dichotomy: that one not free is a slave. For Australians, ‘slavery’ conjures up images of human beings owned as property.7 But they also note that in other cultures, it has a more flexible and transitory meaning. They conclude that it is still the most appropriate term available in English. Aboriginal workers were ‘never slaves in the strict sense, but neither were they free’.8

Aborigines Protection Board (1883– 1940)

The APB was established in 1883 to manage reserves, and it had extensive control over the lives of Indigenous people. It was part of the Department of Police and chaired by the Commissioner of Police. Early records state the Board was to protect Indigenous people and comprised ‘officials… and gentlemen… who have taken an interest in blacks [sic]… and desire to assist in raising them from their… degraded condition’.9 Various legislation enacted from 1909 to 1935 allowed the Board to control Indigenous people’s freedom of movement and personal finances. The Aborigines Protection Amending Act 1915 gave the Board authority to remove Indigenous children ‘without having to establish in court that they were neglected’.10 Institutions were established for Indigenous children who were removed from their families and trained for domestic/manual labour.11 Their wages were placed in the Funds until their apprenticeships ended.12 There does not appear to have been any intrinsic internal financial benefit to the APB in the Funds – it could spend this money in areas considered in the young person’s best interests – but it appears the money was eventually paid to the young people.

That changed dramatically in 1927. The Lang Government in New South Wales introduced a family endowment payment available to all, including Indigenous women. Initially, these were direct payments, but this did not last long. The Australian Government commenced its own family endowment scheme, and, in January 1928, it asked the APB to distribute family endowment payments to Indigenous children.

The APB was reluctant and wrote to NSW Treasury, stating:

The financial inducements finally overcame the APB’s reluctance, with some pressure from NSW Treasury. Arguments by the Australian Government in 1929 highlighted that administering these funds would increase the APB’s control of its funding and Indigenous people.14 The expected reduction in state funding on rations for Indigenous children receiving family endowments, along with the Australian Government’s offer that any administrative costs of distributing the federal benefit would be covered, overwhelmed the APB’s concerns, with a memo stating, ‘it is safe to assume that a saving will be effected in the Board’s ordinary expenditure’.15

In 1930, a memo from the APB to the Chief Secretary’s Department stated ‘the administration of these endowment monies by my Board is resulting, and will result, in considerable saving of the Consolidated Revenue, and such administration is proving to be a most desirable thing from every angle’.16 The APB’s access to the Funds was critical in the face of the 30 per cent funding cuts imposed by NSW Treasury in the 10 years prior to 1937.17 It allowed them to offset the cost of rations and undertake building maintenance on its reserves and missions.

Unsurprisingly, the APB’s satisfaction was not matched by Indigenous communities. In the 1920s and 1930s, dissatisfaction escalated in Indigenous communities as anger grew concerning the operations of the Board. The 1930s Great Depression was a very low point for Indigenous people in New South Wales. They experienced loss of employment but were mostly ineligible for the dole. This was exacerbated by poverty grounded in colonial dispassion, racism and government policies.18 Increasing numbers of Indigenous people were forced back onto APB reserves and missions, as this was often the only way they could provide accommodation and food for their families. By 1935, it is estimated that 30 per cent of the known Indigenous population were forced onto one of the Board’s many reserves and stations.19 This caused immense problems, such as overcrowding and poverty.20

In 1938, the Select Committee of the Public Service Board of New South Wales inquiry into the APB made no mention of the Funds but noted a ‘large accumulation of family endowment funds in the hands of the Board… [and that] these should be reviewed regularly with a view to their reduction’.21 At that time, 623 people were listed as having family endowments held in the Funds. This accumulation of family endowment money was substantial: the Scheme estimated that the 2009 value of these Funds was $2 million.22

Aborigines Welfare Board (1940-69)

The Government responded to the concerns raised by the Indigenous community and the findings of the Select Committee mentioned earlier, highlighting the poor economic management of the APB. In 1940, the AWB replaced the APB. The Aborigines Protection (Amendment) Act 1940 stipulated that Aboriginal people should be assimilated into mainstream white society.23

Control over Indigenous people’s lives continued.24 The new board prioritised the large accumulation of family endowment money held in the Funds, with archival evidence indicating extensive efforts to repay unexpended balances in the early 1940s.25 While NSW family endowment payments ceased in 1941, the new federal legislation for child endowments allowed them to be paid to an authorised third party ‘to ensure the proper application of an endowment granted to an aboriginal native [sic] of Australia’, and the AWB continued using the Funds to manage these payments.26 By 1955, it controlled only 56 child endowments but continued administering apprentice wages.27 This decline in the use of the Funds by the AWB continued throughout the 1950s and 1960s.

In 1967, many Indigenous people were informed that the Funds were being frozen because the AWB was to be abolished and that they should inquire later: only to be told later the money was unavailable. The Department of Child Welfare and Social Welfare received $5,034.95 from the Funds, which was sent to NSW Treasury’s Unclaimed Monies Account in 1970.28 When Indigenous people sought access to these Funds, they were told there was inadequate legal proof of money being owed or that too much time had passed for claims to be viable. For instance, in 2003, Treasurer Michael Egan wrote to one Indigenous campaigner:

Indigenous people persisted in agitating for the return of their money, and Indigenous staff in the Department of Community Services undertook extensive work on the matter. It was this work and a culmination of public pressures that eventually pushed the government to tackle the issue.30 In 2004, NSW Premier Bob Carr issued a public apology addressing the State Government’s legacy of paternalism – specifically, the issue of the Funds.31 Despite this apology, the Scheme commenced work facing immense challenges: proof was required to show that money was owed, but such evidence barely existed.

The records

The Scheme found enormous gaps in the Boards’ records, especially prior to the Archives Act 1960 (NSW). The destruction of records is an enormous problem,32 and evidence is often patchy or non-existent.33 For example, record keeping at Kinchela Boys’ Home was particularly poor, and there were no records for many claimants. Despite extensive efforts, approximately 60 per cent of claims were rejected under the evidence-based framework in the first three years of operations.

The Scheme did have some success with the archives, retrieving limited records from 1897 to 1938 and substantially more from 1940 to 1969.34 In 2006, State Records located 138 boxes of previously unknown records, a stunning find for Indigenous history in New South Wales. An early issue for the Scheme was that processing claims was extremely time-consuming due to poor indexing. This issue and the discovery of the lost records led the Scheme to professionally digitise and index all the Boards’ records.

The archives also contain photographs from 1919 to 1966, which formed the In Living Memory exhibition.35 From 2006 to 2012, the project travelled the state, advertising the Scheme, enabling people to identify family members and providing copies of the photographs. For some, these were the only photographs they had of their family or younger selves.

The stories held in the records are distressing.36 They expose the casual cruelty perpetrated against Indigenous families, children and communities. They resonate with the pain of Indigenous parents pleading with the Boards to return their children and their determination to fight for their rights. The records proved to be profoundly impactful – for many claimants, accessing their stories was life-changing.37

The archives also revealed that the Boards’ management of apprentices and the Funds was problematic, including low wages, employee mistreatment, non-payment of pocket money, and difficulty obtaining payments.38 These practices extended the state’s political domain over Indigenous women. Continual cuts to the Boards’ budgets and NSW Treasury directives to curtail spending led the Boards to control payments through a central account and offset the cost of building maintenance and rations on missions and reserves.39 ‘Little is known’ about how the Funds operated, but the Scheme quickly discovered that, unlike the frontier states of Queensland and Western Australia, the Boards did not take adult Indigenous people’s wages, and the Funds only accrued monies from apprentices’ wages and welfare payments.40

The right to the truth

Key reparation elements include apologies for historical wrongdoings, the right to the truth, and access to information.41 The Scheme’s archival work was arguably its most important and lasting legacy, particularly the discovery of the missing records and indexation of all the Boards’ records. For the first time, Indigenous people could find every reference to themselves or family members in the records.

It was critical to ensure that Indigenous communities had access to information and input into the Scheme’s design. Therefore, the first Scheme Panel undertook extensive community consultations in early 2004, with briefings to regional and local media, as well as Indigenous communities and land councils. It was decided not to undertake a broad media campaign but rather to focus on Indigenous communities, with Panel consultations in 16 key towns. The Department of Aboriginal Affairs and a Scheme-funded Link-Up (New South Wales) worker contacted isolated Indigenous communities. A third campaign informed communities about changes to the Scheme’s Guidelines and encouraged applications before the new closing date in mid-2009.42

While the Scheme was recommended as a template for other states, some considered it a slow and incomplete model.43 Although somewhat successful, it was evidence-based even though, in reality, many records were non-existent. The main criticism was that it did not compensate Indigenous people for stolen wages and that advertising was insufficient, despite the media and community liaison mentioned above.44 Research suggests the cumulative efforts were effective, demonstrated by the number of people registering claims.45 However, the Boards’ archival deficiencies and the Scheme’s evidence-based framework meant that justice was not reached for many claimants.

Diligent, impartial investigations and cultural sensitivity

Strong Indigenous representation was essential to ensuring the Scheme was sensitive to Indigenous communities’ needs and cultural sensitivities.46 Overall, 82 per cent of key staff were Indigenous. This representation was critical to accessibility and gave the Scheme a ‘sense of cultural legitimacy’.47 Additionally, the Scheme’s Indigenous Panel made the final decisions on all claims and provided an independent appeals mechanism. Panel members had extensive political skills as elected parliamentarians and within national Indigenous organisations.48

Further, two ethical principles reflected the Scheme’s attempts to operationalise the Government’s formal apology. First, all processes were open and transparent, and claimants were treated with the utmost respect.49 Second, successful claimants received a personal apology from the Minister.

Early in its inception, the Scheme recognised that it would have been extremely difficult for claimants to provide supporting documentation because most records were inaccessible due to poor indexing and geographical barriers.50 Instead, State Records’ archivists shared all relevant documents with the Scheme for initial assessments.51 Records were forensically examined, as even if it appeared the Funds had been repaid, money might still have been owed.

Deductions from the Funds used by the Boards on food, clothing, lodging and medical care were refunded because, as these young people were, in effect, state wards, the State should bear responsibility for these costs.52 Questionable deductions were also carefully reviewed; although fraudulent deductions did not seem endemic, the records revealed some audacious claims.53 The Scheme refunded such deductions.

Claimants received a one-page initial assessment, a copy of all relevant records, and a report listing other records mentioning them but not concerning the Funds. It was critical that claimants not feel such assessments were just another decision about their lives from a faceless bureaucracy. However, the records are often bureaucratic, reflecting the Boards’ attitudes, and claimants were exposed to potentially re-traumatising content.54 Therefore, where necessary, an Indigenous team member and a social worker delivered the material personally and provided support and advice. While it was identified that more professional support should have been provided, the Scheme’s operations were open and transparent and, critically, ensured claimants were treated respectfully, given their past interactions with state institutions.55

The Scheme also attempted to morally engage with claimants by providing personalised ministerial apologies.56 The literature contains many theoretical disagreements about the role of government apologies. However, the Scheme found that for many claimants, it touched on what one researcher termed the ‘apology paradox’ – that is, an apology cannot undo what has been done, yet ‘in a mysterious way and according to its own logic, this is precisely what it manages to do’.57 Often, claimants were grateful and explained that it was not about the money – it allowed them to tell their stories and be believed, and many said it was a lifechanging experience. Many felt the formal government apology was critical in acknowledging the historical injustices they had experienced.58

Because the Scheme was established under administrative (rather than legislative) powers, an appeals mechanism was needed for claimants who wished to have their claim reviewed; otherwise, they would have had to undertake legal action, an often costly, lengthy and distressing process. The Scheme’s Indigenous Panel provided claimants with an avenue to have their applications reviewed. The Scheme’s staff had no discretionary power when assessing claims, but the Panel had absolute discretion to review each case. It could endorse, question or reject any assessment.59 Thus, it provided an impartial and culturally appropriate review body for claimants.

Ensuring the Scheme could accommodate any required changes was critical. Section 1.8 of the Guidelines permitted the Director-General of the NSW Premier’s Department, Panel members, or the Minister to depart from the Guidelines in the interests of justice and equity. The Panel took action under section 1.8 when support was required on individual claims or for a particularly disadvantaged group.60 For example, while it was usually clear that claimants had been at Kinchela Boys’ Home, virtually no records existed of any work, apprenticeships or accounts in the Funds; hence, no claims could be approved because repayments were calculated based on the records. In 2009, the Guidelines were amended to permit a flat repayment of $11,000, and, using section 1.8, the Panel approved the Kinchela claims, and a level of justice and diligence was achieved.61

The NSW Government’s action to address such historical injustices many decades after the AWB was abolished was in no way prompt. Whether the Scheme undertook prompt, diligent and impartial investigations is a different matter. The surviving claimants were no longer young, and it was essential to process claims swiftly if they were to see justice regarding the Funds. Many claimants felt frustrated at the lengthy process. However, while the Scheme was expected to emerge fully formed after its announcement in December 2004, an enormous amount of work was undertaken for its launch in February 2006.62 This lapse between governments’ announcements of new projects and the need for frameworks to ensure effective implementation is a common challenge for many Western bureaucracies, and the Scheme was no exception.63 Nevertheless, establishing the Scheme under existing administrative powers rather than legislation reduced costs, allowed it to commence immediately after receiving government approval and enabled flexibility where required.

Adequate reparations

Where the Scheme found money was owed from the Funds, it was repaid in total and indexed to the current dollar value (an average of $10,209).64 By March 2008, most direct claims were assessed, and repayments were made to 93 direct claimants totalling $978,025.

However, by 2009, 87 per cent of descendant claims still required finalising in the 18 months until the Scheme’s closure.65 The revised Guidelines extended the Scheme to 2011, simplified the assessment process and specified the flat $11,000 repayment. Forensic examinations were no longer needed to calculate the actual money owed; it was simply necessary to establish that money was owed and make the repayment.

Of the direct claims, 76 per cent failed on the evidence. Further, the Scheme’s repayments totalled $12.9 million, suggesting a success rate of only 20 per cent for descendant claims, primarily due to poor records. While the Scheme’s intention was clear, publicity campaigns mistakenly advertised that it encompassed all stolen wages issues. Hence, many people sought repayments based on varying definitions of stolen wages, most of which fell outside the Scheme’s ambit.66

The Scheme did work to address two potential financial difficulties for claimants receiving a payment from the Funds.

Firstly, there was concern regarding the treatment of payments by the Australian Taxation Office (ATO) and Centrelink. Centrelink was extremely supportive, and a regulation enacted in 2005 ensured Scheme repayments did not affect successful claimants’ social security benefits.67 Negotiations with the ATO proved more difficult. Initially, it indicated a tax-free ruling would only be given if the Scheme repayments were compensation payments. This was a real setback because it was totally at odds with the Scheme’s key principle: it was a repayment scheme, not a compensation scheme. This was non-negotiable from the NSW Government’s perspective. NSW Treasury officials stepped in and negotiated a compromise, which led to the ATO ruling that the Scheme’s repayments would be tax-free.68

Secondly, the Scheme addressed the issue of the 308 Indigenous wards and their Funds that were transferred to the Department of Community Services in 1969. These claims fell outside the Scheme’s scope. The Scheme was given access to the department’s ward files and informed the department if money was owed. By early 2008, the Panel had referred nine such claims, and the department had repaid $60,000 to six claimants.

Conclusion

Within the legal and administrative framework set by the NSW Government, the Scheme successfully met many elements of international human rights reparations. However, because of its specific requirement that claimants needed evidence of money owing from the Funds, it did not address the broader need for just collective reparations and failed to recognise the intergenerational trauma suffered by Indigenous people due to colonialism and assimilation policies.

The Scheme could be considered a ‘rough justice’ reparation scheme.69 It tackled the issue of repaying monies from the Funds but did not attempt to address the harder question of reparations for broader historical wrongdoings. It was a partial act of reparation by New South Wales, a compromise due to political and budgetary constraints.

Full compensation for the harms of colonisation to Indigenous populations can never realistically be achieved.70 Monetary compensation for historical injustices is insufficient, yet ‘the status quo of no justice is even less morally defensible’.71 The Scheme repaid $12.9 million from the Funds, successfully pursued money owed outside its ambit, and ensured repayments were tax-free and did not affect claimants’ welfare benefits. It could not compensate for the removal of children, loss of lands and cultures, and inadequate or stolen wages.

Importantly, by ensuring that claimants did not sign away their legal rights, the Scheme retained avenues for further action, effectively upholding the principle of ensuring no legal bars to multiple reparations for the same historical injustice.72 It also offered a lasting legacy in its actions to protect the Boards’ records and ensured transparency and access for Indigenous people to these remnants of their histories.

This story demonstrates the Scheme’s role in the interactions between New South Wales and Indigenous people. It is a tiny part of the larger mosaic, revealing and defining the truth about the treatment of Indigenous people in Australia in service to our ‘duty to remember’.73