Request accessible format of this publication.

1. Aboriginal economies

Authors: Paul Irish and Michael Bennett

Hear directly from the author

Aboriginal people in New South Wales have provided for their families for countless generations. In ancient times they found ways to live in diverse and changing environments.

Their adaptability did not cease when Europeans arrived. In the wake of frontier violence and dispossession, Aboriginal survivors identified new opportunities to allow them to provide for their families and stay on Country. Many of these efforts and initiatives were stifled by restrictive government policies over the past 120 years or so, but the desire for economic autonomy has never disappeared.

In this chapter, we try to trace some of the continuities, challenges and ruptures in the economies of Aboriginal people in New South Wales. As non-Aboriginal historians, we do this based largely on archival records, and recognise the limitations of bias and omission inherent in this. But you can learn more from the words and experiences of Aboriginal people in some of the references at the end.

It can be very difficult today to trace connections between how Aboriginal people currently live and the ways of their ancestors long before Europeans arrived in what we now call New South Wales. Non-Aboriginal people are often unconsciously shackled to the inaccurate but stubborn idea that Aboriginal people cannot change or adapt without losing their ‘authenticity’. Just think about what comes to mind when you hear the terms ‘remote’ versus ‘urban’ Aboriginal communities. This idea has blinded us to the adaptability of Aboriginal people and the ways that they have organised obtaining the essentials of life: their economies. This adaptability can clearly be seen when we take the long view.

Across New South Wales, Aboriginal people lived through the cooling, freezing and thaw of an ice age. At its peak around 20,000 years ago, average temperatures were up to 10 degrees cooler. Some elevated areas contained glaciers, and though most of the state was ice-free, drastically lower sea levels exposed a vast coastal plain kilometres further east than our current coastline. Their ancestors had already lived across the south-east of the continent for countless generations by then, camping in places like the Willandra Lakes and burying their dead on the shores of Lake Mungo. Not only was the climate different, but in this period Aboriginal people lived alongside the gigantic ancestors of kangaroos, emus, wombats and snakes.1

As the ice age ended and sea levels and temperatures began to rise about 18,000 years ago, new economic opportunities arose. Along the coast, the rising waters steadily and visibly drowned the former coastal plain over many generations, but in the process created a fishing paradise. Freshwater rivers turned tidal, and vast estuaries with extensive new shorelines like Sydney Harbour were formed – along with the beaches we know today, backed by tidal lagoons and lakes. The sea reached roughly its current level around 6,500 years ago, and then rose and fell a few metres several more times before finally stabilising.

Aboriginal people adapted to these new environments. The remains of coastal campsites (often called middens) along the new shores show that a wide range of fish and shellfish were being gathered, alongside plants and land animals. Larger sea mammals were also eaten, such as a dugong butchered near Gamay (Botany Bay) in Sydney 6,000 years ago, during a period of higher sea level when the bay was larger than today. This discovery in the 1890s demonstrated to Europeans that Aboriginal people had lived in Australia through significant changes in the environment.2

Private collections of JVS Megaw.

The economies that Aboriginal people developed over many millennia were complex and culturally driven. The visible and familiar aspects of their lives were those most recorded by Europeans: the procuring, exchange and use of foods, medicines, tools and raw materials of various kinds. But Aboriginal exchange was not a simple matter of trading goods of an agreed value. Their societies were (and still are) structured around extended family kinship. When Europeans arrived, New South Wales was home to hundreds of family or clan groups, dozens of different language areas, as well as broader networks of relationships through shared spiritual beliefs and ceremonial practices.

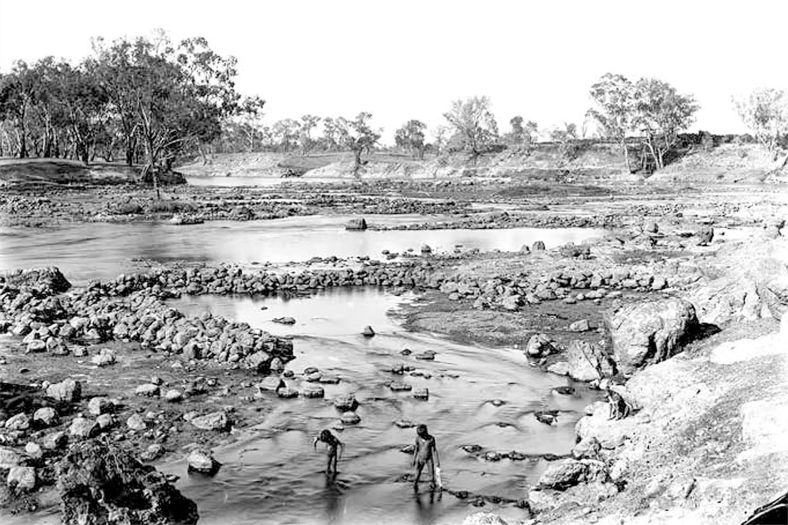

Henry King, ‘Aboriginal fisheries’, fish trap on the Barwon River, Brewarrina, NSW, ca. 1890, AIATSIS Collection KERRY_KING.001.BW-N03159_01.

Unlike a currency-based economy, Aboriginal people had reciprocal obligations to family: complex webs of relationships that influenced their interactions and exchanges, spiritual beliefs that bound them to their traditional Country and its vegetation and wildlife, and cultural responsibilities to maintain across the countries they were linked to through birth and marriage. Exchange occurred between individuals, families and in larger group gatherings. It could involve physical goods such as food and raw materials, but also knowledge, song and marriage partners, all wrapped up in this context of kinship and reciprocal obligations.

Although well-known to researchers, poor public understandings of the complexity of Aboriginal cultural and economic life help explain why simple labels such as ‘Aboriginal agriculture’ have recently seemed attractive to fill the gap.3 Among other issues though, they do not adequately consider the spiritual and kinship aspects of Aboriginal economies.4 For those wishing to delve deeper into these issues, we have included some key references at the end of this chapter.

Some examples help illustrate the connections between the spiritual and economic worlds of Aboriginal people. Along a large bend in the Barwon River in Ngemba Country at Brewarrina in northern New South Wales are the extensive Ngunnhu fish traps. Ngunnhu is undeniably a remarkable feat of engineering, creating a network of weirs and ponds from many thousands of stones along a bend in the river, allowing Aboriginal people to trap fish in high or low river flows.

According to Ngemba people though, the fish traps were designed by the Aboriginal creation figure Baiame and built by this two sons Booma-ooma-nowi and Ghinda-inda-mui.5 The use of resource areas like Ngunnhu was governed by the cultural protocols and spiritual obligations that we have already mentioned, sometimes including specific ceremonies to increase the fertility and productivity of these areas. Access to, and gathering of, foods and raw materials more generally was also influenced by clan affiliations and individual prohibitions on totemic animals and plants.

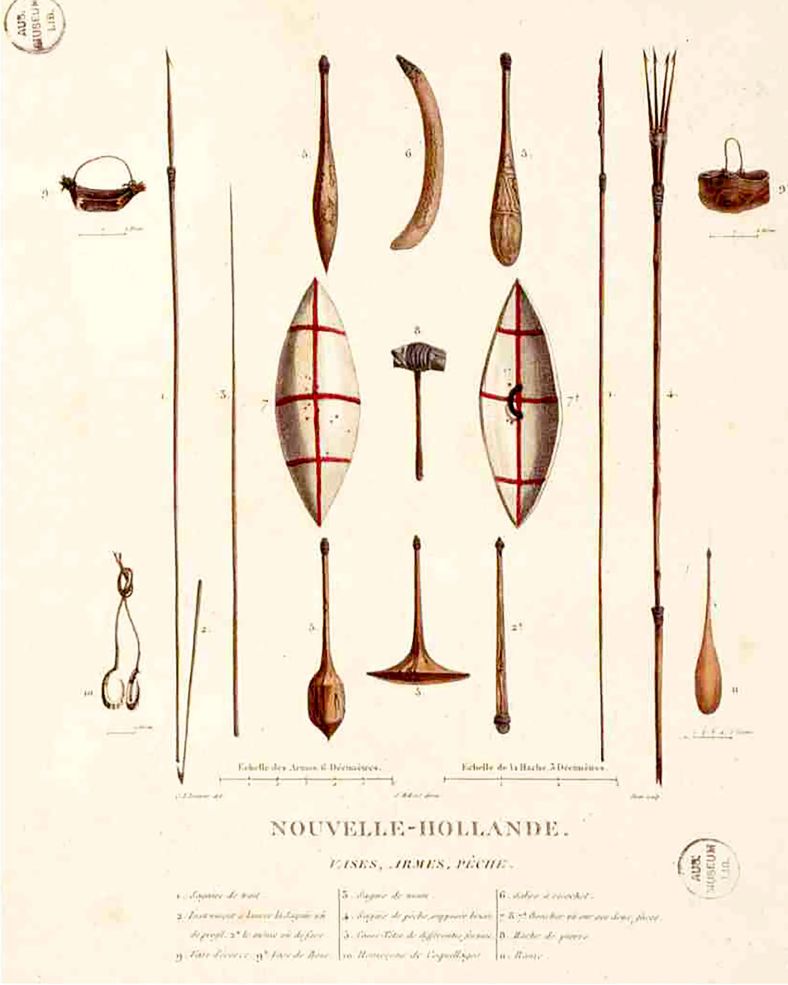

New Holland – Baskets, Weapons and Fishing Gear. by CA Lesueur (artist), J Milbert (editor), Dien (engraver). In Peron & Freycinet 1824, Plate 30. [Full reference to be added once original image sourced].

For some surviving examples see State Library of NSW, 2023, Wadgayawa Nhay Dhadjan Wari (they made them a long time ago) (online), https://www.sl.nsw.gov.au/exhibitions/wadgayawa-nhay-dhadjan-wari (Accessed 6 December 2023).

Aboriginal economies were enabled by technology. In the archaeological record of New South Wales, we can see the introduction of new technologies and raw materials over time into the increasingly diverse Aboriginal toolkit.

Stone axes helped enable the construction of watercraft, as well as shields, tools and weapons; bone points were used in hunting and fishing, and to sew skin cloaks together; and shell fish hooks were adopted mainly by women and changed the nature of coastal food gathering.6

Creating these tools often involved strongly bonding multiple components together, and required deep environmental and scientific knowledge of raw materials and their properties. Tools sometimes had ceremonial purposes and could be adorned with incised designs. They were functional, but also individually crafted things of beauty.

When travelling and obtaining food, Aboriginal clans sometimes fragmented into smaller groups or individuals, but also came together in much larger gatherings. In some areas, kangaroos and other land animals were driven by large hunting parties (sometimes using fire) into clearings or large woven bark fibre nets where they could be captured.7 Some seasonally plentiful foods enabled large Aboriginal gatherings, such as for netting fish or wildfowl along inland rivers.

Perhaps the best documented example, though, is the bogong moth feasts in the Snowy Mountains.8 These fatty moths are highly nutritious and hibernate in large numbers on the walls of alpine caves in warmer months. Aboriginal people from surrounding areas gathered in their hundreds at the foot of the mountains to harvest and cook the moths. These gatherings were also a time for ceremony, marriage, trade and the settling of disputes, demonstrating the intertwined nature of Aboriginal economic and cultural life.

Trade of raw materials, tools, knowledge and song also occurred along vast exchange networks. For example, fine-grained stone for making spearpoints and other tools was traded many hundreds of kilometres from Mount Daruka near Tamworth to the Bourke district on the Barka (Darling River).9 Certain types of hard volcanic stone were also highly sought after for making axe heads, and were sometimes traded many hundreds of kilometres across the traditional countries of a number of groups from where they were quarried.10 Recent research has started to match individual axes to the specific volcanic outcrop from which their stone was sourced, giving new insights into the nature of Aboriginal exchange in ancient times.11

Even this brief look at aspects of traditional Aboriginal economies makes it clear how deeply entwined the everyday and spiritual aspects of life were. Aboriginal people were spiritually bound to their Country and had extensive cultural obligations to clan and broader kinship networks.

The arrival of Europeans in Sydney in 1788, and the spreading invasion across the area of New South Wales over the next century, was cataclysmic for the many Aboriginal clans and nations across the State and beyond. The radiating frontier claimed countless Aboriginal lives through violent conflict and disease, while the survivors found themselves dispossessed of their lands and resources. In short, traditional economies were severely disrupted and some practices were discontinued. But we often highlight this and leave the story there, overlooking the essential story of the Aboriginal survivors.

Aboriginal people responded to the changes and challenges of colonial times in a deeply cultural way, drawing on their cultural knowledge and spirituality to remain living on their traditional Country as much as possible on their own terms.

In Sydney, for example, Aboriginal people very quickly learned who was who in the new colony. They began to interact selectively with Europeans of influence, and others who were sympathetic to them. They acquired tools that they desired such as metal fish hooks and axes by trading traditional objects, foods or by working for Europeans in various capacities.

As the Sydney population grew over the following decades, Aboriginal men and women found new opportunities for some degree of economic autonomy. They used their traditional environmental knowledge to gather and sell materials such as resin, native fruits and flowers, acquired fishing boats and used them to run commercial fishing and recreational fishing and tourism businesses, and made traditional implements such as boomerangs for sale.12

We can also see these adaptations elsewhere across the State. Numerous Aboriginal men, women and children were engaged in the expanding pastoral and agricultural economies in the 19th century, undertaking a variety of tasks. Many had little choice but to seek work in these industries after they lost access to much of their traditional food sources, but this kind of work also allowed them to draw on their traditional knowledge and skills and remain living on Country.

Aboriginal maid ironing at ‘Kaleno' station – Bourke, NSW, ML At Work and Play – 05733

For example, farmers and pastoralists often relied on Aboriginal people to strip bark when establishing their properties. The bark strippers adapted a traditional skill to remove large sheets of bark which was then used to construct huts and sheds. Others worked as timber-getters, clearing the land for crops and animals. As farms and stations developed, Aboriginal workers learned new skills including reaping, shepherding and fence building. Some Aboriginal women also worked as domestic servants in homesteads, again doing a variety of tasks: cooking, ironing, sewing, gardening and delivering babies.

Aboriginal employees in the 19th century were rarely permanent – a choice Aboriginal people often made themselves.

For example, Aboriginal workers on Alexander Berry’s Cullunghutti near the mouth of the Shoalhaven River rarely worked for more than a couple of weeks each year, usually in winter when corn was harvested and in spring when sheep were washed before shearing.

They often worked in small family groups, highlighting the ongoing significance of kinship within Aboriginal communities. Most were paid in rations and clothing although some had relatively generous yearly contracts in the 1840s worth about £40. Working on Cullunghutti, which continued throughout the 19th century until residents were relocated to Roseby Park Aboriginal reserve, only contributed a small fraction of their total subsistence and most relied on traditional fishing, hunting and gathering to survive.13 There was a similar pattern on Yulgilbar, a property on the Clarence River about 50 km north of present-day Grafton occupied by Edward Ogilvie in the early 1840s. Aboriginal men and women worked as shepherds but, much to Ogilvie’s chagrin, temporarily left their jobs when important ceremonial business took place.14

There was a notable increase in Aboriginal pastoral employment, particularly in areas west of the Great Divide, following the discovery of payable gold at Sofala in 1851.

Many white workers left for the gold fields, leaving pastoralists with severe labour shortages. Some changed their view: whereas before they were content to see Aboriginal people driven from their properties, they now regarded those same people as valuable, replacement labour.

Aboriginal people themselves noticed the change. Mary Jane Cain, born near Coonabarabran in about 1842, recalled in the late 1920s that Aboriginal people came to the ‘rescue’ of the pastoralists when the white workers hurriedly left.15 Missionary William Ridley noted on a tour of the Bundarra, Mehi and Barwon Rivers in north-western New South Wales in 1853 that the ‘scattered settlers are now very much dependent on the blacks for the management of their vast flocks and herds’.

Both Aboriginal men and women were working as shepherds at this time.16 The advantage for Aboriginal people was that they could continue to live on their traditional Country while supporting their families. Historian Heather Goodall has called this phenomenon ‘dual occupation’.17

Another sector where Aboriginal people adapted traditional skills to the colonial economy was policing. From the late 18th century through to 1973, numerous Aboriginal men (and occasionally women) were paid to work as guides and trackers, recognising their deep knowledge of the landscape. Although it often took them far from home, it also allowed them to provide for their families. Not long after the first Europeans arrived, Aboriginal men were sometimes engaged to recapture escaped convicts, a pattern that continued throughout the first half of the 19th century.

Later, particularly after the crossing of the Blue Mountains in 1813, Aboriginal guides took explorers deep into the interior of the colony, acting as interpreters and cultural brokers as the expeditions progressed. In a dark period of colonial history, hundreds were drafted into the infamous native police which operated in northern New South Wales and Queensland from 1848, attacking Aboriginal camps and killing the inhabitants.18

The employment of Aboriginal trackers became increasingly formalised after the current NSW Police Force was created in 1861, with trackers attached to almost 200 stations at different times. Notable trackers include Billy Dargin who pursued the bushranger Ben Hall between 1862 and 1865.

Photograph album of the employees and inhabitants of the Coolangatta Estate, Shoalhaven River, N.S.W. ML PXA 1252 (image 17).

Many trackers were also skilled horse breakers and handlers, abilities learned when growing up on pastoral properties. Some lived in the police stables and spent more time looking after police horses than they did working on particular cases. Isaac Grovenor of Yass, for example, worked as the tracker at the Redfern Police Stables for almost 30 years from the mid-1920s. There is no record of him tracking criminals, but he was renowned for training even the most cantankerous of police horses.19

Other trackers used their horse skills in other areas. Bob Curran (aka Bally Rocket), worked as the tracker at Moruya in the mid-1870s. He was also a successful jockey, riding horses for Ettienne de Mestre (the trainer who won the first Melbourne Cup).20

Aboriginal trackers were paid a small wage, given a uniform and sometimes a weapon. They were not, however treated equally, or considered official police officers. For example, Alec Riley worked as the tracker at Dubbo for almost 40 years from 1911 to 1950.

Highly regarded by the broader community, Riley helped solve numerous murders, including the killing of three itinerant workers by Andrew Moss near Dubbo in 1939. Despite a decorated career, Riley was shocked to learn that upon retirement he was not eligible for a police pension.

Trackers were not always given the support or acknowledgement they deserved, although the opening of an honour wall at the Goulburn Police Academy in 2023 goes some way to remedying the oversight.21

We can see these inequities even more clearly in farm work, where relationships between pastoralists and Aboriginal people were not always peaceable and productive. Power and authority clearly stood with the pastoralists and their white employees. There are numerous examples in the papers of Aboriginal labourers being arrested for breaching the Master and Servants Act 1902 which governed contracted labourers in the middle of the 19th century.

Walgett Police Station

The police could be called for other disputes as well. Ebenezer Orr, who owned Garrawilla near Coonabarabran and heavily relied on Aboriginal labour from the 1850s onwards, did not hesitate to call police to arrest an Aboriginal man with strong ties to the area who was suspected of stealing 100 sheep.22

In other instances, discipline was handled by staff on the property. For example, pastoralist Edward Ogilvie was known to flog Aboriginal workers for minor indiscretions at his Yugilbar property.23 Billy Bogan, an Aboriginal youth aged about 12 years, was working on Bumbaldry near Cowra in January 1876 when he got into a dispute with an overseer, who locked him in a room. The overseer used harsh disciplinary measures and went to get a whip to thrash Billy. Fortunately for Billy, the overseer dropped dead from a heart attack before he could administer the punishment.24

Throughout much of the 19th century, these colonial inequities were largely interpersonal. The government through much of this time exhibited a profound ‘indifference’ to Aboriginal people, and there were few state-wide policies or laws with respect to their treatment.25 Though this led to unpoliced abuses, it also gave Aboriginal people the space to try to live as much as possible on their own terms, as we have seen.

All this began to unravel in the closing decades of the 19th century. The NSW Government formed the Aborigines Protection Board (APB) in 1883, initially focused on creating Aboriginal reserves and supplying blankets and rations to those in need. They eventually sought greater control over Aboriginal people and the passage of the Aborigines Protection Act 1909 through the parliament; subsequent amendments gave the APB a legislative base to formally segregate Aboriginal people and remove children from their parents.

Effective incarceration on reserves and missions, combined with increasing government control over their lives, stifled or wiped away many of the economic initiatives Aboriginal people had been able to put in place over the previous century.

A particularly distressing era of Aboriginal ‘employment’ relates to the removal of children by the APB, which we know today as the Stolen Generations.26 Many stolen children were sent to institutions specifically established to house them, including Bomaderry Childrens Home, Cootamundra Girls Home and Kinchela Boys Home, although many other institutions were also used. The legislation also established an apprenticeship scheme where the children, once they reached approximately 14 years of age, were sent to live and work for non-Aboriginal families throughout New South Wales. Girls were mainly apprenticed as domestic servants, while boys were commonly sent to work as unskilled labourers on farms.

Many studies clearly demonstrate the abusive and degrading treatment that many apprentices received at the hands of their employers.27 Furthermore, although apprentices were paid a minimal wage, the APB remained in control of the money, permitting only a small weekly allowance. Many apprentices were unable to obtain the balance of their wages at the end of their term and the money remained within the Treasury.

A redress scheme operated in the early 2000s to return the money to surviving apprentices (see chapter 12) – although some were dissatisfied with the amount, which did not include an element of compensation. The scars of removal and apprenticeship are still borne by the survivors, but many are finding some solace in the corporations established to assist those institutionalised at the three homes mentioned above.

Residents on Aboriginal reserves did not always rely on APB rations or outside work to support themselves. On some of the larger reserves, residents grew their own crops for personal consumption and the market. Wheat was commonly grown in inland areas such as Warangesda on the Murrumbidgee River; sugar cane and maize were commonly farmed on north coast reserves.28

Photograph album of New South Wales Aboriginal reserves, ca.1910, 15A Warangesda ML PBX492

But intensified demand for land by non-Aboriginal people, particularly following establishment of the soldier settlement scheme post-WWI, resulted in the revocation of many reserves and the loss of productive Aboriginal farm land.29 The residents were pushed onto larger reserves or stations where arable land was limited.

Nevertheless, Aboriginal farming on reserve land continued into the second half of the 20th century in limited fashion. For example, residents of Cabbage Tree Island on the Richmond River near Ballina established a sugar cane cooperative on the island in 1960, formally leasing the land from the APB’s successor, the Aborigines Welfare Board.30

A common form of employment in the 20th century was seasonal vegetable and fruit picking, and other labour-intensive jobs such as cotton chipping (weeding). Market gardens, orchards and cotton farms expanded rapidly in the middle decades. Manual labour was required at different points of the year, and many gardeners, orchardists and farmers turned to Aboriginal families as a cheap labour source.

The work again had a strong social and kin component. Don Murray of Collarenebri chipped cotton with his family near Wee Waa in the 1960s. They camped on Crown land near the edge of town but were subject to an unofficial police curfew after sundown.31

Others had more positive experiences. Coral Brown of the south coast recalled that some families combined seasonal picking with other work such as timber cutting, while still travelling as a family. She recalled in 1998 that:

Although the demand for unskilled pastoral labour declined in the 20th century as many of the large properties were broken up, some Aboriginal men found work as shearers, travelling throughout the state in spring as the shearing intensified.

William Ferguson, who grew up on pastoral stations along the Murrumbidgee near Darlington Point, became a shearer in the early 1900s, travelling as far as Gulargambone on the Castlereagh River. A witness to the exploitation of Aboriginal and non-Aboriginal labour in the shearing sheds, Ferguson became a union organiser. He later used these political skills to campaign for Aboriginal citizenship and against the Aborigines Protection Board in the late 1930s, co-founding the Aborigines’ Progressive Association and helping to stage the Day of Mourning Aboriginal civil rights conference and protest on 26 January 1938.

Aboriginal shearers worked throughout the 20th century and once again there was a strong familial element. Dick Carney recalled in 2014 that he worked for many years in a team of nine shearers, all brothers. They travelled as far west as Louth and as far south as Cooma. In between seasons, Dick earned extra money by carving and selling artefacts such as ‘boondies’ (clubs), a skill taught to him by his father. His brother Tom Carney was still shearing in 2014.33

But for many others, the decline in demand for rural labour forced some Aboriginal families to consider looking elsewhere for work. The NSW population is now largely urban with over 70 per cent living in major cities. Particularly since WWII, there has been an influx of Aboriginal people from rural New South Wales (and other parts of Australia) into Sydney – initially into the inner-city suburbs in the vicinity of Redfern and Waterloo, and then into western Sydney.34

Growing industrialisation of the broader economy meant that many new arrivals found work in factories in the inner suburbs, and other places such as the railway workshops at Eveleigh or the abattoir at Homebush. Equal pay was not always offered, but the rights of Aboriginal workers were sometimes supported by unions such as the Miscellaneous Workers Union of Australia.35 In recent decades, better access to education and training has seen Aboriginal workers enter just about every profession, though there are still significant disparities and inequities for many Aboriginal people in the broader economy.

Stories of Aboriginal economies could (and do) fill many books, and much more could be written. Work is a key part of Aboriginal family histories: stories of pride, hard work (and hardship), often linked to migration and sacrifice in pursuit of better futures. They are also integral to the broader histories of many more industries than those we have mentioned, such as fisheries, whaling, railways and maritime work – not to mention professional sport – but Aboriginal contributions are often still overlooked.

In recent decades, as Aboriginal communities in New South Wales emerged from a century of government intervention and oppression, there has been a strong desire to re-establish the relative economic independence that many ancestors were able to forge in the 19th century.36

Current Aboriginal economic initiatives are still often characterised by a continuing sense of kinship and community obligation. As such, they can require some specific nurturing in a highly competitive, market-driven economy to ensure that they can survive and thrive. Getting this right remains an ongoing challenge for government, business and the NSW community more broadly. It requires listening, understanding and action to be able to respond effectively to the needs and wishes of Aboriginal people who are striving both to reclaim their economies and to continue to provide for their families as their ancestors have done for countless generations.