Request accessible format of this publication.

11. From the Bradfield Plan to Transurban’s Tollways

Authors: Anne Gilmore and Peter Spearritt

Sydney is a city cut in half by its wide harbour and the Parramatta River. Restricted in its development by the Pacific Ocean to the east, and rivers and mountains to the north, west and south, it poses topographical challenges for any form of transport.

The colonial government built railways radiating out from Sydney, catering for the movement of both manufactured and agricultural goods and people. Bridges could be built over the Parramatta River, but Sydney Harbour proved much more intractable, requiring a long and high bridge to allow for shipping to proceed to the wharves in Pyrmont and Balmain.

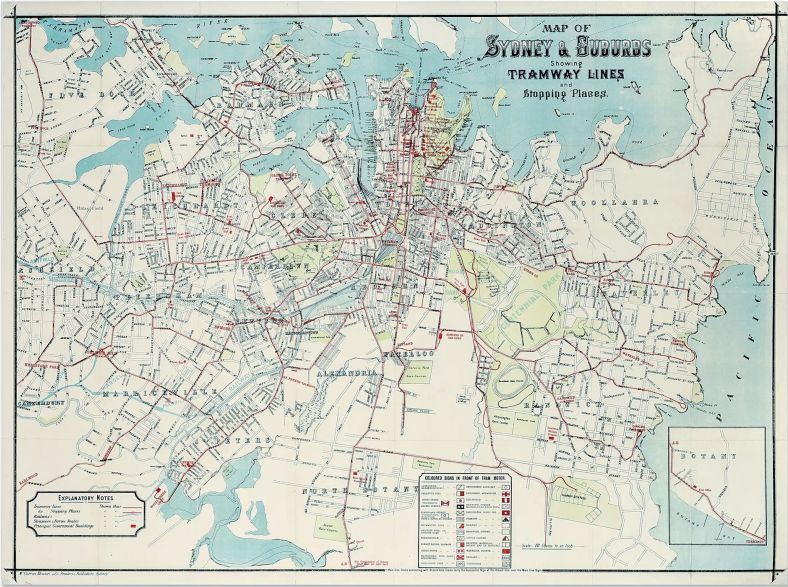

In the last decades of the 19th century, cities around the world were expanding their public transport systems. Underground railways had already been built in London, Paris and New York, and those cities also had electrified tramway systems. Sydney developed a tramway network, servicing the inner and middle-ring suburbs, to get people to school, to shop, to work and to recreational activities, especially the beaches.

Sydney and Melbourne were neck and neck in population until a depression in the 1890s impacted Melbourne more than Sydney. The NSW capital surged in population to become the first Australian city to pass the one-million mark by the mid 1920s. At this stage, even with population growth, Sydney appeared to have unlimited land. In the 19th century, government added to its colonial coffers by selling freehold and/or leasing Crown lands.1 Waves of suburban subdivisions fanned out along the railway lines. In inner Sydney, terrace houses still dominated – following British precedent but as soon as you were a few kilometres out of town you could see, from both the railway and tramlines, freestanding houses being built on their own blocks of land, usually carved out of much larger landholdings, whether rural land or grand estates.

Compared to other rapidly growing cities in Europe and the United States, Sydney appeared old-fashioned. The inner suburbs had narrow roads, and its railways were still pulled by steam, with soot covering washing along all the lines. Forward-looking Ministers for Transport were constantly being lobbied not only by electors but by the Railway Commissioners, who oversaw Australia’s largest railway system. Electrification had worked for the tramways, drawing energy from the coal-powered station at Ultimo, so why couldn’t the railways also be converted to electricity? This would involve an extraordinary investment of NSW Government funds, because it not only required new rolling stock but also the insertion of overhead wires into railway routes that had been designed for steam.

The NSW Government appointed royal commissions to advise on planning Sydney and its transport needs in the first decade of the 20th century, including work on the vexed issue of a direct link between Sydney and North Sydney, then served by overcrowded vehicular and passenger ferries. Into this maelstrom of debate about ‘improving Sydney’ stepped an engineer, J. J. C. Bradfield, employed by the Public Works Department, who became a leading advocate of town planning ideas and a proponent of a transport scheme to cope with rapid urban growth.2 The grand centrepiece of his plan was a bridge across Sydney Harbour that would cater for both railway lines and motor vehicles.

The Bradfield Plan

Bradfield’s plan for electrifying the suburban railways and an underground railway for the city centre – which would service both the sandstone government department offices and the huge city emporiums – gained the support of both the Labor Party and most non-Labor parliamentarians, with the only doubters being country members who worried that less money would be available for ‘railways outback’. Revenue projections were optimistic, and both property owners and local government were told that they would benefit from increased land values and higher council rates. Nowhere was this emphasis more appealing than on the north side of the harbour, where suddenly a harbour bridge crossing, an electrified North Shore Line and a planned new railway route to Manly and Narrabeen would open up thousands of potential housing blocks.3

Government decision-making on both the scheme and how to pay for it stalled during and after World War I, but by the early 1920s the relevant acts of parliament had been passed. An arch design was decided for the harbour crossing, which would be strong enough to support four train lines: two on the western side and two on the eastern side. Bradfield based his recommendation on Hell Gate Railway Bridge in New York, opened in 1915. The British firm Dorman Long & Co won the international tender to build the bridge.

The Harbour Bridge became the largest engineering project of its era in Australia – much more spectacular than a new dam, because the arches, rising from either side of the Harbour, could be seen from vantage points all over the city. Jack Lang, as Treasurer (April 1920 to April 1922) and as both Treasurer and Premier (June 1925 to October 1927 and November 1930 to May 1932), remained the key political backer of both Bradfield and funding his scheme. The Sydney Harbour Bridge Act 1922 legislated that its capital cost would be partly met by a levy on property owners in the City of Sydney and a ‘betterment’4 tax on property owners in the northern municipalities. This was politically acceptable to the Labor Party because although most of its voters were tenants, they saw the Bridge as opening cheap land for the working class. The other two thirds of the capital cost were to be borne by the railway commissioners, who looked forward to a huge increase in passenger revenue.

Business interests and the Taxpayers Association lobbied for a toll to be levied to replace the betterment tax. The Lang Labor Government legislated for a bridge toll. On the opening of the bridge in March 1932, manned toll booths – on both the northern and southern approaches – levied tolls on drivers, passengers, cyclists, with special rates for vans, lorries, horse-drawn drays (then still common), and per-head on agricultural stock; but pedestrians, because of mounting unemployment during the depression, would not have to pay. The betterment tax wasn’t abolished until 1937, when Premier Bertram Stevens, a conservative accountant who had worked in the Treasury Department in the 1920s (and who at that time had been sidelined by then-Premier Jack Lang) succumbed to lobbying by the Taxpayers Association.5

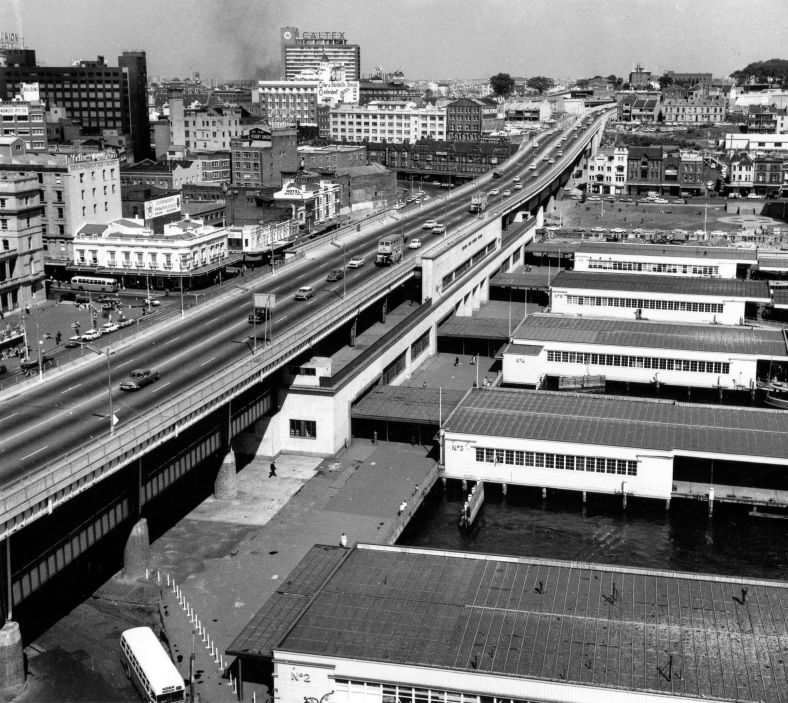

With Sir Betram as both Premier and Treasurer at the helm of the State’s finances after Lang’s sacking by the Governor, Sir Phillip Game, in May 1932, restraint became the order of the day. Only two new rail lines were built, one between Kingsgrove and East Hills (1931) and another to Cronulla (1939), making it the only surf beach readily accessible by rail. Trams continued to deliver holiday makers to Bondi (and other eastern suburbs beaches) and to Manly. The proposed eastern suburbs railway remained on hold, as did the proposed railway to the northern beaches. The city underground loop remained incomplete until the opening of the Circular Quay railway link in 1956, with the later addition of the Cahill Expressway atop the station.

Abandoning and rebuilding a tramway network

By the late 1930s, Sydney had a comprehensive rail and tramway network. The suburban railway lines had been electrified, and like the trams, were powered by government-owned power stations. The tramway network covered most of the growth areas of the metropolis that were not serviced by rail, including Manly and the northern beaches, and Bondi and the eastern beaches, with the tram even delivering prison visitors to Long Bay Jail. The tram, with its own right of way for much of its length, also took punters to the races and cricket fans to the Sydney Cricket Ground. The eastern suburbs had their own tram line to Rose Bay and Watsons Bay, but they had to wait many more decades to get a long-promised railway line.6

Army survey maps compiled in the late 1920s and early 1930s show that over 90 per cent of Sydney’s population lived within a 15-minute walk of a tram or rail line.7 The subdivision booms that this network facilitated meant that home buyers and property investors (60 per cent of all households in Sydney were tenants at the 1947 census) could build new houses along the rail and tram lines. All this development augmented the Treasury’s coffers, from stamp duty on property sales to inheritance tax when owners died. And when the State Government reintroduced land tax in 1956, property provided yet another source of revenue for Treasury.

In the 1950s and the 1960s the USA and the UK abandoned their tramway systems, as did every Australian city except Melbourne, the only English-speaking city in the world to retain its entire network.8 Buses were seen as cheaper and more flexible modes of transport. In Sydney, a cash-strapped State Government, having lost its income tax power to the Australian Government in World War II, concentrated on augmenting water supply to keep pace with a subdivision boom. The Metropolitan Water and Sewerage Development Board (MWSDB), a government-owned statutory authority, built the Warragamba Dam. The NSW Government’s other priority was for its NSW Housing Commission, with Commonwealth assistance, to build tens of thousands of houses and flats for public tenants.

The National Roads and Motorists’ Association Ltd (NRMA), which campaigned vigorously against trams, repeatedly complained about congestion on King Street in Newtown, George Street in the CBD, and Military Road on the North Shore. Getting rid of trams would free these roads from traffic congestion, so the argument ran. Needless to say, motor manufacturers (Ford, Holden and Leyland with the bus supply contracts), and the oil companies, rejoiced. Hundreds of houses were demolished at intersections all over Sydney to make way for new petrol stations.9

To close the tramway system, the Labor State Government had to guarantee the members of the powerful tramway union would all be offered jobs on the new government-owned buses. Only Sydney and Newcastle had large tram networks to be replaced with bus routes. Getting rid of the trams meant that well-placed parcels of real estate were open for development and new uses, The most spectacular of these sites was the Bennelong Point Tram terminus, which would be given over to a proposed Opera House, the subject of an international design competition.

The closure of the system also enabled the two tram lines on the eastern side of the Sydney Harbour Bridge to be converted to traffic lanes. Getting rid of the trams improved traffic flow for just a few years, because the exponential increase in car ownership led to even worse traffic congestion. The most common cartoon depictions of the Sydney Harbour Bridge in the 1960s and 1970s were drawings of traffic jams. The city centre and all the roads out of it became traffic sewers, from the Pacific Highway in the north to Parramatta Road in the west. Because buses plied the same routes as the cars, their travel times also became more and more unreliable.

The rebuilding of Sydney’s tramway system, once one of the world’s largest, is full of irony. Fortunately, some of the original reservations have been re-used, most notably along Anzac Parade. The tram line to Dulwich Hill appropriates a former freight rail line, while the tram to Darling Harbour uses a former goods line. A government contract to design, construct, operate and maintain new tram lines was signed with the ALTRAC consortium in December 2014. In 2016, because of a sharp increase in construction costs and faulty travel time calculations, the Auditor General found that the cost benefit ratio had fallen from 2.4 to 1.4.10 The Randwick Line opened in 2019, and now serves the University of New South Wales, as well as sporting and racing facilities, and the line

to Kingsford opened in 2020. Thirty-five million passengers travelled on these lines in 2022-23.

The motorised city: freeways and tollways, 1950s to 1990s

Sydney’s public transport system boomed during World War II, not least because cars were scarce and severe restrictions were placed on petrol sales. Both the railways and the tramways experienced a marked increase in patronage. Well before the end of the war, senior public servants in both the state and the federal governments were busily planning the demobilisation of armed services and preparing for a post-war world.

Sydney faced a severe housing shortage, as very few new houses had been built since the outbreak of war, with building restrictions and ‘manpower’ allocations all aimed at maximising the war effort. Over half of all houses and apartments at that point were rented, and many, especially older houses, were in a shocking condition. Most of the subdivided housing blocks from the 1930s were unsewered, as were the new subdivisions planned and sold in the 1950s. Housing blocks were relatively cheap and owner building common. Most of the new houses were still within a kilometre of a railway station or a tramline, and if further away cycling was common in a society where only one in five households could afford a car. The train and the tram continued to be the transport backbone of the metropolis.11

In 1948 the Cumberland County Council, covering the entire metropolitan area, produced the most detailed and impressive town plan ever conceived for Sydney. The planners noted that the city-centred public transport system was at its best when moving people between the city centre and the inner industrial suburbs and their homes. The Department of Main Roads, in its 1945 publication Bulldozer, argued that ‘expressways’ would be needed for ‘commuters in a hurry between the heart of Sydney and the outer suburbs’.12

None of the planners predicted just how quickly car ownership would grow, nor the deleterious impact on public transport use. The proportion of all trips by private vehicle in Sydney rose from 13 per cent in 1946-47 to 47 per cent in 1960, an almost four-fold increase. Between 1961 and 1981, that proportion almost doubled from 47 per cent to 87 per cent. Many households acquired two cars, especially from the 1970s, because by then a majority of adult women had driver licences.13 The number of public transport trips in Sydney fell from 850 million in 1946-47 to 457 million in 1981, while the population more than doubled to 3.2 million. Public transport revenues fell, and the majority of users were school students, the aged, and households that couldn’t afford to buy and maintain a car.14

Home ownership flourished, with the proportion of owners and purchasers increasing from 43 per cent in 1947 to 68 per cent in 1986. Most households had off-street parking, and even the walk-up home unit blocks that spread out along every rail line in the 1960s and 1970s usually had at least one car space per unit. Two out of three work trips were made by car, and public transport only dominated for the journey to work in the city centre.15

The city and the suburbs became subsumed by traffic. Some routes, including Parramatta Road to the west and the Pacific Highway to the north, suffered long traffic snarls well beyond peak hour. Accidents were common, and motorists were often late for work. A new concrete arch bridge at Gladesville, paid for by the government, opened in 1964 and helped alleviate congestion between the north and south.

But pressure on the Harbour Bridge and its approaches continued to mount, so the Labor Government in 1965 embarked on demolitions for the ‘Warringah Freeway’, cutting North Sydney and Neutral Bay in half, and requiring the demolition of hundreds of terrace houses. Partly paid for by an amendment to the Sydney Harbour Bridge Administration Act 1932, the new freeway was underwritten by toll revenues.

The first section of the freeway opened in 1968 and it has been widened and lengthened, in fits and starts, ever since.16 The Government also embarked on a new tollway, a vast engineering undertaking north of Hornsby, cutting through huge swathes of sandstone, proceeding over the Hawkesbury River, reducing the travel time to the rapidly growing Gosford Wyong region and Newcastle. The first section opened in 1964, thrilling motorists with its grand vistas. It has been augmented ever since.17 The toll was lifted in 1990 when the Australian Government decided that directly funded national highways had to be toll free.

Sydney Metro

In the 1980s and 1990s there was a sharp fall in capital expenditure on Sydney’s railway system. The Granville rail disaster in 1977 (when a derailed train dislodged an overhead road bridge pylon, causing many deaths) forced the Wran Government to better maintain the existing rail system. The only new routes opened were to Olympic Park (1998, using a branch line built for a long-closed abattoir) and a privately funded airport link with a very high ‘access’ fee for airport passengers, so investors could recoup their costs. These new lines were seen as vital to the success of the 2000 Sydney Olympics and to avoid the transport chaos of the 1996 Atlanta Olympics. Despite this important investment, most railway stations in Sydney still didn’t have lifts, let alone disabled access.18

By 1999, Premier Bob Carr, who had been in office for four years, sensed a public getting increasingly fed up with longer and longer commutes, whether by car or by bus. Many Sydneysiders had no access to the rail system, so his Action for Transport Plan 2010 included a North-West rail link. In 2005 the Labor Government promised a metro rail that was quietly dropped after the 2007 election. By 2010 a frustrated electorate turned against the Labor Government, which lost the March 2011 election.

Successive NSW Labor governments simply couldn’t decide what to do about either new public transport options or increasing road congestion. The Government knew they were on shaky ground with the electorate and undertook numerous reviews. Just prior to leaving office in 2005, Carr announced the Metropolitan Rail Expansion Programs (MREP) that would have seen three new rail connections.19 Frank Sartor, a former Sydney Lord Mayor and then Labor Government Minister, later wrote that transport policy was one of Labor’s major failings:

Sartor singles out Treasury’s obsession with retaining a AAA credit rating after the Global Financial Crisis (GFC) as a crucial factor underlying inaction. Treasurer Michael Costa was certainly considered by Dr Peter Newman (who was appointed to the newly established Infrastructure Australia advisory board) as a major obstacle to improving Sydney public transport.21 The Sydney Morning Herald reported that Treasurer Costa had said ‘junking the Government's promise of the North-West railway’ was required to reduce the capital expenditure necessary to retain the Standard and Poor’s AAA rating.22

The new Coalition Government under Barry O’Farrell set up Infrastructure NSW, an independent body to plan and source funds for new infrastructure projects, with Nick Greiner (a former Liberal Premier) chair of the board. Infrastructure NSW produced the State Infrastructure Strategy 2012-2032. Greiner clashed with then-Minister for Transport Gladys Berejiklian, who prepared a competing masterplan, the NSW Long Term Transport Master Plan 2012, claiming it as the State’s ‘first integrated transport strategy.23 While acknowledging that some funding would come from the NSW and Australian governments, a clear mantra throughout the report is to source new funding options from public-private partnerships and user-pay schemes.

This report also outlined the rollout of the Opal Card system, introduced gradually from 2012, based on London’s Oyster Card.24 The Opal Card encompasses Sydney, the Central Coast, Hunter/Newcastle, the Blue Mountains, Illawarra and the Southern Highlands. The Treasury and the Transport Department monitor usage, fare income and costs on the publicly owned rail and buses, privately operated trams and ferries, and privately owned bus routes. Both major political parties continue to offer school children, other students, pensioners and seniors free travel or a low daily rate. It gets a lot of people out of their cars, as do the capped rates for weekly commuters.

State revenues improved after the GFC, with a huge increase in land tax and stamp duty because of high turnover in property, from investors to first home buyers. Treasury funds were also augmented from gambling revenue, vehicle registration and driver licence fees. The Coalition Government, sold off Port Botany and the poles and wires of the electricity distribution system, and the resulting influx of cash enabled it to start planning for Sydney Metro, with early work funded by a Restart NSW fund established in 2011. Asset sales would go 70 per cent to the city and 30 per cent to country areas.25

Two major consultancy firms, PwC and EY, undertook a series of cost-benefit analyses which supported light rail and Sydney Metro. Unlike the existing rail system, the metro lines would only take single-level carriages, not the double-decker rolling stock that had expanded capacity since the mid 1960s. Those carriages increased seated capacity but didn’t allow quick ingress and egress during peak hour. Metro systems, with services every four to five minutes, move passengers quickly, with many standing cheek-to-jowl at peak hour. In a large city, where the road-and-land-use system is long established, new lines require the resumption of many private properties, including residential structures and businesses. ‘Sydney Metro has spent more than $2 billion acquiring 511 properties over the past three years, including the 23-kilometre connection to Western Sydney Airport’, wrote the Sydney Morning Herald at the time.26

The biggest question mark over Sydney Metro is whether the proposed routes in the outer suburbs, dominated by single dwellings on their own blocks, will generate enough passengers into the system, especially with such households opposing medium and high-density development. Will the system be sufficiently integrated (in terms of moving people to destinations without more than two changes) to get drivers out of their cars? The inner city gets even more stations (four abutting the CBD, two in North Sydney/Crows Nest), but on some outer suburban routes stations are 6 km apart, so passengers may have to walk or cycle up to 3 km or compete for a commuter parking spot before their journey can start.

Public transport remains the backbone of many trips in Sydney, including the journey to work in the Sydney CBD, North Sydney and other city centres, including Chatswood and Parramatta. Apart from road congestion issues, the costs of paid parking in such locations are prohibitive. Public transport dominates the journey to school, TAFE and university, and is the only main source of independent transport for young people and the aged, apart from walking or cycling. At any one time, roughly one third of the population do not drive. After a lull during the COVID-19 pandemic, Sydney’s public transport system had 643 million trips in 2022-23, including 288 million by rail, 261 million by bus, 21 million by Metro, 39 million by light rail, and 14 million by ferry.27 Total usage had only increased by 40 per cent since 1988, yet the metropolitan population had increased almost two thirds, to 5.3 million. It should be noted that flexible working and working from home has continued post-COVID-19.

The motorised city II: Transurban

In societies where there is an expectation that government has a responsibility to provide ever-improved and expanded infrastructure and services, political parties look for ways other than the public purse to fund such development. State governments in Australia traditionally had a very strong role in promoting and supporting economic and social development. The ability of the NSW Government to raise the funds required for bigger projects was hampered by the loss of the income taxation rights to the Commonwealth since World War II and the abolition of inheritance tax in 1981. At times of pinch points in the finances of the NSW Government, an array of financial arrangements have arisen to tap into private funding for high capital cost projects and subsequent operating costs. What is commonly termed public-private partnerships (PPPs) come in a multitude of guises, currently ‘broadly’ defined by the NSW Government as:

The engineering firm Transfield, in partnership with the Japanese company Kugamai Gumi, proposed, built and operated the Sydney Harbour Tunnel, the first large scale infrastructure PPP in New South Wales. With no government policy in place, the Greiner Government enacted the Sydney Harbour Tunnel (Private Joint Venture) Act 1987 to direct such an arrangement. The tunnel owners negotiated an advantageous deal for themselves, with the government guaranteeing a revenue steam for 30 years.Glen Serle, ‘New Roads, New Rail Lines, New Profits’, p116, and Paul Ashton, ‘1987: the year of new directions’, historical essay on the 1987 cabinet papers, most readily accessed via www.mhnsw.au/nsw cabinet papers.

Tony Shepherd, a key player in the development of Victoria’s first tunnel and pay road CityLink, became an inaugural Director of Transurban, the company set up to deliver Melbourne’s first PPP.30 Transurban has grown to become a ‘monopoly supplier of a heavily regulated public good’31 as the provider of tollways in the eastern states of Australia and is the owner of the integrated toll payment system Linkt.32

Transurban has developed a sophisticated funding and infrastructure model which has enabled governments to expand road infrastructure without having to take on the initial capital cost and financial risk. Government foregoes the income benefits that arise from owning and operating tollways during the period over which Transurban has concession rights.

The relationship between Transurban and the NSW Government is closely intertwined with able negotiators at Transurban winning decade-long extensions on tollway concessions, incorporating agreements to build in regular toll increases tied to inflation. The toll-free public road system becomes much more time-consuming to travel on, and increasingly toll roads are almost impossible to avoid.

The cleverest aspect of Transurban’s strategy is to not only be the builder and operator of its own routes but to buy underperforming toll roads cheaply, including the Military Road E Ramp, initially operated by Connector Motorways until it went into receivership in 2010. The previously government-owned and (for a period) untolled M4 Motorway from Parramatta to Homebush has now been upgraded and extended and subsumed in WestConnex, the whole shebang finally opened in 2023.

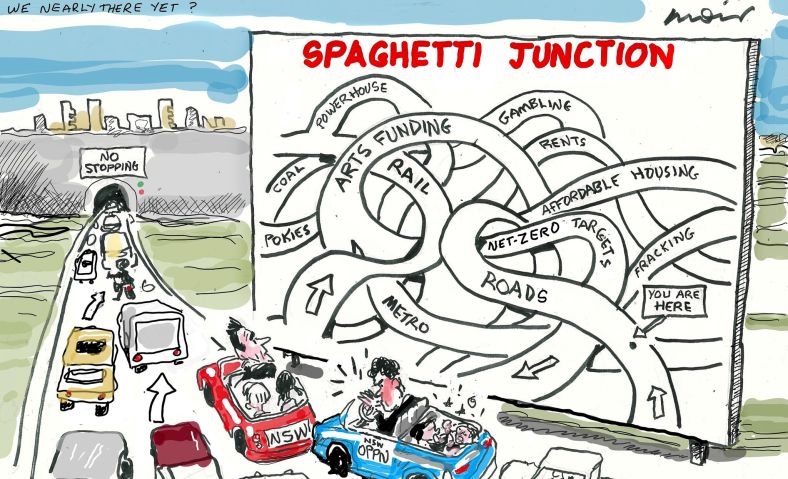

Tollways are most remunerative when they are all linked up, graphically symbolised by the Rozelle Interchange, which opened to much fanfare in November 2023. Plagued by congestion in its initial period of operation, the Government had to make immediate changes to its own ingress and egress routes. Alan Moir, a veteran Sydney Morning Herald cartoonist, couldn’t resist the temptation to depict what he called the Spaghetti Junction.33

Following increasing concerns from motorists over the levels of tolls across Sydney, the Perrottet Coalition Government in 2022 introduced a toll relief rebate program, to lessen the burden on heavy users. The Minns Labor Government elected in 2023 promised its own toll relief (a $60 per week cap on tolls) as well as an independent review of tolling in New South Wales.

As a monopoly provider it will be intriguing to see how Transurban responds to heightened environmental concerns about road use and climate change. Are these toll roads so path dependent that they continue to champion motor vehicles, even if per-capita demand should decline due to demographics and climate imperatives? Will the NSW Government end up having to acquire toll roads before the current agreements expire, some of which have already been extended to 2060? Just as very few experts in the first decades of the 20th century predicted just how quickly car ownership would grow, it is also possible that car ownership might fall away and new forms of transport emerge that won’t require gigantic road systems that could be retrofitted for other uses.34 With the gradual uptake of electric vehicles, the Australian Government will see a decrease in its fuel excise revenue unless a new funding steam is determined.