Request accessible format of this publication.

10. Australia’s determined transition to decimal currency, 1966

Author: Kylie Andrews

On 14 February 1966, Australia made its official transition to a new Western currency, shifting from the British system of pounds and shillings to one of dollars and cents.

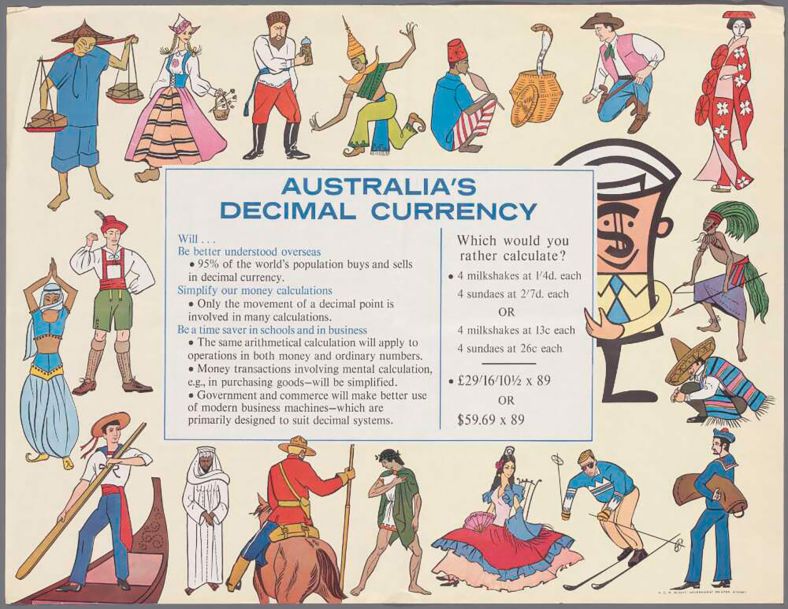

It was long overdue, and a key step in the progressive dismantling of our imperial apparatus. There had been several failed attempts to move to decimal currency. However, by the mid 20th century, the reasons for change outweighed those for staying loyal to the British system. As the post-war boom brought high wages, low unemployment, increased immigration and rapid technological and industrial change, the inefficiencies of an imperial monetary system were causing unnecessary losses to commerce and industry, impeding our ability to function as a modern, efficient nation in an increasingly inter-connected global community.

With decimal currency, Australian commerce and industry could embrace new international enterprises and expand global trade and export opportunities. It would also be easier to teach and much easier to learn, improving the nation’s financial literacy. But how to implement such a monumental task? How to change a fundamental part of every Australian’s life, with as little disruption as possible?

Australia’s shift to a decimal system in 1966 was remarkable for being executed under budget, ahead of time and without increasing inflation. It was co-ordinated by the Decimal Currency Board, a purpose-built federal organisation that initiated collaborative networks to help plan, organise and manage the process. In New South Wales, the people of NSW Treasury played their part, aligning with their federal counterparts. They helped structure and shape state legislation, advised parliamentarians and worked with the Public Service Board to prepare the state’s public servants and modify the entire public system network. It was remarkable how people came together: politicians and public servants, finance, business, industry, and media all joined in to advise, formulate strategies and commit to implementation.

Why transition to decimal currency?

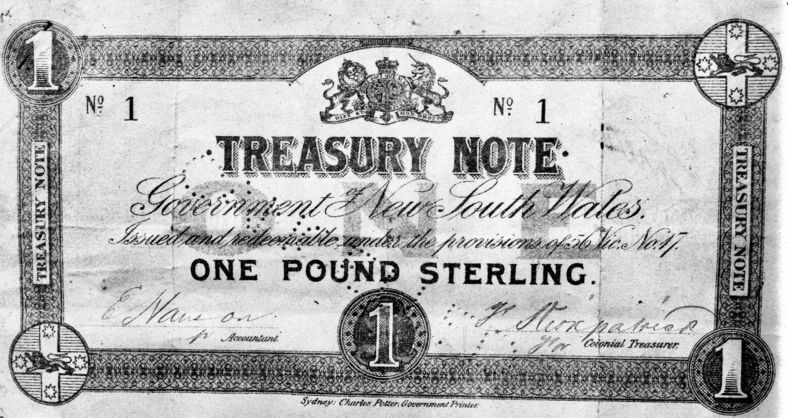

Australia’s first decimal currency ‘Select Committee’ was established soon after Federation in 1901 in response to growing concerns over its ‘cumbersome’ monetary system. It was argued the difficult process of accurately calculating 12 pence per shilling and 20 shillings per pound impeded Australia’s financial literacy. The new federal government rejected the Committee’s recommendations for change, however, reasoning it was more important to replicate the currency of our major trading partner and cultural prototype.1

In the 1930s, the issue was exacerbated by concerns that Australia was isolating itself from other ‘modern’ nations by adhering to the antiquated British system; a Royal Commission subsequently surveyed the issue. According to economist Selwyn Cornish, while the 1937 Commission praised the efficiencies of a decimal system and recommended revision, it also recognised the obstacles: the Australian pound was still ‘pegged’ to British currency and Australians were complacent about embracing change.2 However, momentum finally shifted after World War II as the nation became primed to redefine its economic, political and cultural identities.

Australian commerce and industry also felt the impact of calculation errors and time-wastage more keenly. In response to these growing concerns, the Decimal Currency Council was convened in 1957, instigated by economist and Australian National University vice-chancellor Sir Leslie Melville. It quickly endorsed change.3 It was anticipated a ‘magnitude of savings’ could be gained through decimalisation, as more than 11 million pounds were being lost per year.4 In classrooms, a disproportionate amount of time was also being spent teaching children how to navigate the knotty imperial arithmetic.

With other nations watching closely, Australia’s decimal transition provided an opportunity to demonstrate our growing economic proficiency, correlating to what Donald Horne described as a ‘national identity crisis’.5 In 1959 Treasurer Harold Holt established the Decimal Currency Committee (DCC), with Walter Scott as Chairman and Neil Davey as Secretary. The combination of Scott and Davey’s industrial expertise and scholarly percipience was, according to Cornish, ‘critically important for the successful transition to the new currency’.6 A new Currency Act was finally instituted in 1963. It laid out the structure of the new decimal system, framed how the nation’s monetary machinery would be converted and compensated, and established the Decimal Currency Board (DCB) as the key organising body.7 It also determined the changeover day, or ‘C-Day’, would occur on 14 February 1966.8

Planning and facilitating change

Many people were involved in facilitating the transition to decimal currency, from treasurers to public servants, media executives to the ‘Dollar Jills’ recruited to educate and reassure the public. The new DCB enlisted the DCC’s executive advisors and Walter Scott and Neil Davey quickly began to implement a ‘multitude’ of plans. (Davey would become known as ‘Mr Decimal’ for his guiding role in the process.) The nation’s ready embrace of decimal currency was precipitated by a combination of strategies. The first substantial challenge would be to provide the nation with decimal-based business machines; converting existing systems as well as introducing new machinery. The new currency would have to be designed, printed and minted, then it too had to be circulated around the country.9 Davey, Scott and the DCB sought expertise from a cohort of advisors from government, industry and media. Another helpful factor was the implementation of a comprehensive publicity campaign to educate and inspire the public’s support.

The Currency Act 1963 set a two-year window that accommodated both old and new currency. This gave the banks, public institutions, business owners and retailers plenty of time adjust – they could get their machines ready (both new and converted) and ensure their staff were trained to adapt to the new system.

A plenitude of brochures and booklets were printed, such as the Decimal Currency Manual (1964), explaining how to prepare and train staff, outlining arrangements for machine conversions, showing how to set up helpful merchandise displays, and suggesting how to maintain customer goodwill.10 The DCB also studied South Africa’s approach to decimalisation and adjusted their plans accordingly.11 Following C-Day on 14 February 1966, the new currency was adopted rapidly. The two-year timeframe allowed for both currencies to be used, and the ‘old money’ deposited was kept by banks with only new currency available for withdrawals. Within a few months, approximately 85 per cent of the old money was filtered out.12 The DCB acknowledged ‘the community at large had adjusted to the new currency much more quickly than had seemed likely and, indeed, that there was some impatience of a prolonged transitional period.’13

The Treasury, New South Wales and intra-national bipartisanship in action

In the years leading up to C-Day, NSW Treasury consulted with its federal counterparts and joined the NSW Public Service Board and the Auditor General’s Department to facilitate the transition.14 Treasury also helped the NSW Government determine the costs and financial compensations for updating business machines and counselled how to adapt new postage systems.15 Treasury staff played an important role in the state’s Decimal Currency Steering and Survey Committee (DCSSC). Albert Oliver, Deputy Under Secretary of the Treasury, was a key advisor. The committee was charged with ensuring an efficient changeover to decimal currency within the Public Service. It was instrumental in suggesting parameters for the new state legislation that would modify all pre-existing legislative references to imperial currency and helped determine how best to adapt industrial awards and agreements. It also advised on conversion matters relating to Income Tax, Unemployment Relief Tax and Social Services Taxes.16

The New South Wales Decimal Currency Act was passed in December 1965.17 In response to the national agenda for decimalisation each state needed to initiate legislation to accommodate the new currency and address inconsistencies in existing laws.18 The State DCSSC suggested a blanket amendment that would apply to all state law, including regulations and legislation’.19 Newly elected Premier and Treasurer Robert Askin (Liberal Party) subsequently tabled legislation for a ‘comprehensive umbrella Act’ that would facilitate the transition; he stressed the goal for legislative change was one of ‘simplicity’.20 When discussing the bill, Askin described it as ‘a sensible approach to what may at first appear to be a most complex problem’ and reassured Parliament the new Bill reflected the recommendations of the DCSSC.21 He also acknowledged how important it was to get support from the wider political community, that it would require a group effort to address these many ‘complex problems’. All government departments and instrumentalities would have to review the proposed bill. It would require, he said, ‘the reading and examination of virtually the whole of the statute book. I am sure that honourable members will agree that this in itself represented a most weighty task.’22 Askin went on to declare:

Across the floor, Labor’s Member for Concord Thomas Murphy gave his support for the bill and the contributions of the NSW Public Service:

A series of accompanying Acts followed, covering the remaining exclusions, such as stamp duties and superannuation. Fifty years after the event, commentators were still acknowledging the potency – and rarity – of Australia’s co-operative approach to reform, and of the public service leadership that underpinned it. In 2014 Journalist Gerard McManus wrote:

Designing, minting and printing

A nation’s currency has always been a key representation of its values and identity. Design of one’s currency, like one’s flag, indicates how citizens imagine the nation.26 The naming and design of Australia’s new currency was a crucial component of Australia’s cultural rejuvenation. In the post-war era, our political landscape was dominated by a long run of conservative governments, however, Australians were becoming restless with ‘tradition for tradition’s sake’.

They were excited when invited to suggest names for the new currency, an opportunity to exercise self-determination. Participating in surveys and contests, the public eagerly proposed names such as ‘Australs’, ‘Boomers’, ‘Kangas’, ‘Dinkums’ and ‘Schooners’. In June 1963 the Menzies government overruled public opinion and instead selected ‘The Royal’ for notes, and ‘crowns’, ‘florins’ and ‘shillings’ for coins.

It was unprepared for the public outcry that followed. Political objections and blistering media commentary called for a less ‘antiquated’ designation.27 Cabinet came to begrudgingly accept ‘the preference clearly shown by a substantial majority of the Australian people’ and adopted the more modern (and more universal) denotation of ‘dollar’ and ‘cents’.28 Menzies retired in March 1966, just a few weeks before those ‘dollars’ and ‘cents’ were launched.29

The design of notes and coins meanwhile, progressed more smoothly. Graphic designer Gordon Andrews created a series of resonant images that highlighted the nation’s history and achievements, featuring agriculture, art and culture, the built environment, literature and technology. The new notes, Brett Evans explained, ‘told a useful and unifying story: Australia was a serious place with some serious achievements; it had Indigenous people with a culture of their own; it was a constitutional monarchy – in other words, a democracy'.30 Stuart Devlin, a gold and silversmith, won the support of the Advisory Panel on Coin Design thanks to his beautifully evocative and cohesive ‘family’ of designs that celebrated native animals and birds.31

In anticipation of the immense minting and printing task ahead, plans began in 1958 to establish a dedicated national mint in Canberra. It would be different from the existing Melbourne and Perth mints, which were divisions of the British Royal Mint (at whose London base Australian coins were also produced). A major challenge for the Decimal Currency Board was to mint and stockpile enough coins for the entire nation to use, and to have them ready by February 1966. After consultation with state police forces, the coins and notes were tactically transported around the nation in convoys of trucks with armed guards 5 days prior to C-Day in ‘Operation Fastbuck’.32

‘Out with the old and in with the new’

With its iconic ‘Dollar Bill’ campaign, the DCB initiated a concept that cleverly melded Australia’s beloved bush-legend identity with allegorical imagery representing both nations. The plucky Australian Dollar Bill, playing his guitar, was depicted as a charming and appealing character, compared to his staid, bow-tie-and-tails-wearing, trombone-playing British counterpart. Dollar Bill portrays the new currency as a positive, practical solution to an outdated, burdensome system. Illustrating the resonance of the campaign, sixty years after the event older Australians are still able to sing along to the informative and memorable jingle:

The song is tellingly titled ‘Out with the old and in with the new’. Composer Ted Roberts wrote the lyrics and set them to the iconic bush ballad Click Go the Shears. The Dollar Bill characters were conceived by Monty Wedd and illustrated by animator Laurie Sharpe. They were voiced by Kevin Goldsby and Ross Higgins. Dollar Bill and his message were extensively reproduced in a wide range of publicity and merchandising material, drawing diverse pieces of communication into a more cohesive national message. For example, retail and trade outlets frequently used displays featuring the iconic character, and newspapers volunteered to publish the weekly Dollar Bill comic strip (doing so for 15 months).33

Another factor aiding Australia’s smooth decimal transition was the printing of scores of informational booklets and brochures, explaining the process and guiding the way forward. Governmental, commercial and educational bodies distributed millions of items for the nation.34 In addition to the informative booklets and guides, the DCB implemented an information campaign that encouraged government, retail and industry to put people ‘on the ground’ to explain the process and answer questions across a range of sectors.35 In 1965 Elaine Connor was working for Woolworths and Rockmans in regional Queensland, and was initially tasked to train staff for the changeover

Connor also became the unofficial trainer for the community at large, answering local shopkeepers questions, however her role became extraneous once Dollar Bill appeared on television, the campaign resolving many of the public’s questions and concerns.37 In 1965, Carol Limmer was an ambitious young woman working at the Commonwealth Bank when she was invited to be a ‘Dollar Jill’. The recruiters sought young spokeswomen who were well informed, intelligent and attractive. Limmer was tasked to run the first decimal display at the ‘Ekka’ Agricultural Society show, one of many regional and national events that the teams of ‘Dollar Jills’ were sent to.38 The DCB communications team embraced exciting entertainment innovations to capture the public’s attention during these in-person information sessions, for example, the new ‘Aniform’ technology was very popular. Limmer remembered children and their parents enjoyed the on-the-spot dialogue with both Dollar Bill and Dollar Jill in animated question-and-answer performances.39

Conclusion

Although most of the decimalisation process was determined at a federal level, New South Wales had a great deal to address. NSW Treasury staff allied with their peers from the Public Service Board and Auditor General’s Department and together worked diligently to facilitate the transition. They contributed to the New South Wales the Decimal Currency Steering and Survey Committee and advised government on legislative change. They also strategically assessed the complex requirements of adapting the systems and machineries of the NSW Public Service to the new decimal system. Progress would have its price. But it proved to be less than expected. The cost to the nation was originally estimated to be between $60 and $75 million, though the final expenditure for the transition came in under budget at $45 million. Due to a well organised and collaborative process, the planned two-year machine-conversion period was completed six months early.40

Although it was an issue that inspired debate and discussion, politicians and public servants from different ends of the political spectrum and across a range of regional and structural divides, worked together to get the job done. On the eve of C-Day, Prime Minister Harold Holt praised those involved in making the long journey for change. The nation’s efficient embrace of decimal currency, he said, was proving to be ‘a tribute to our maturity as a people who can welcome progress and can co-operate successfully for its achievement.’41 It was an incredibly challenging and inconvenient process, but it was a price we were prepared to pay to become more economically resilient.