Request accessible format of this publication.

6. Monetising the social contract, 1911–20

Author: Peter Hobbins

Hear directly from the author

Introduction

There was a new mood in the air through the second decade of the 20th century. This outlook was captured by The Songs of a Sentimental Bloke, first published in Sydney in 1915. ‘Knowin’ that ev’ry coin o’ kindness spent / Bears interest in yer ‘eart at cent per cent’, wrote poet C. J. Dennis.

Australians had never enjoyed so much kindness from their local, state and federal governments, barely a decade after the introduction of universal suffrage. They were also ‘Measurin’ wisdom by the peace it brings / To simple minds that values simple things’.1

Many of the simple things that Australians aspired to – a rewarding job, a healthy family and a decent home – were materially assisted by NSW Treasury over 1911–1920. They were part of an evolving social contract, in which individuals forfeited their own self-interest to benefit the greater good. The most obvious means of monetising this exchange was via increased taxes, duties, licences and fees for government services. But this decade also saw Australians make unprecedented sacrifices in response to momentous global events, notably World War I (1914–1918) and the subsequent pneumonic influenza pandemic (1918–1919) – often called the ‘Spanish flu’.

Faced with this willingness to forego personal safety in the name of collective security, the State responded generously. Historian Jill Roe believes that legislative and fiscal gestures during this era represented the swansong of Britain’s ancient chivalric code. Across the political spectrum, she suggests, leaders saw both personal and electoral merit in the ‘ideal of the “gentleman” stressing honour, service to his fellows and respect for all women’.2 By actively funding experiments in the new social contract, Treasury sought to replace individual chivalry with more egalitarian State support.

Federation and compensation

On 1 January 1901, as the former colonies became the federated Commonwealth of Australia, a time bomb started ticking in the nation’s Constitution. Section 87 (known commonly as the ‘Braddon Clause’, after Tasmanian Premier Sir Edward Braddon) ensured that the states received a minimum of three quarters of the customs duties and excises collected by the new Australian Government. Over 1901-1910, the Commonwealth paid well above this minimum to NSW Treasury, totalling 27,595,743 pounds. In 1909-1910, for instance, the Federal contribution equalled 58.7 per cent of the State’s entire cost of government.3

But the Braddon Clause was time-limited to 10 years from Federation. Its expiry in 1911 saw the Commonwealth shift to a revised reimbursement model, paying a flat 25 shillings per capita. This formula allowed for simple budgeting, since the annual sum only increased with a rise in the NSW population, then 1,646,734.

The new arrangement immediately diminished the State’s consolidated revenue, however. By June 1912, this dramatic decline effectively emptied the Treasury Chest – the Treasurer’s main source of discretionary ‘cash’.4 Even the nature of money changed, with the Australian Bank Notes Act 1911 (Cth) imposing prohibitive fees on currency issued by institutions other than the Federal Treasury. For the first time, all six states shared a single suite of Australian coins and banknotes.

New South Wales’ revenue shortfall was partly compensated by land sales and taxes. For instance, the Stamp Duties (Amendment) Act 1914 levied new duties on probate for the wealthiest 10 per cent of residents.5 Elected for the first time in 1910, the Labor government under Premier James McGowen also experimented with limited control of the means of production. Accordingly, Treasury opened accounts under the Special Deposits (Industrial Undertakings) Act 1912 to receive revenue from State-run facilities such as brickworks, quarries and the Government Dockyard on Cockatoo Island.6 Established in 1911, the Treasury Fire Insurance Board meanwhile became ‘one of the most powerful and influential financial institutions in the State’.7 Extending well beyond fire insurance, the board provided both a welcome income stream and a wide range of policies for government enterprises, premises and staff.

In return for rising taxes, Australians expected greater services. In New South Wales, the municipal responsibilities of ‘rates, roads and rubbish’ had largely devolved to councils in 1906 via the Local Government Act. The Commonwealth then assumed responsibility for old age pensions in 1909 and invalid pensions in 1910, saving NSW Treasury more than 200,000 pounds per year. The State thus looked to invest its social capital elsewhere.

A showpiece of societal improvement was championed by Treasurer John Dacey in the final days of his life: the Housing Act 1912. This legislation established a Housing Board as a sub-department of the Treasurer’s portfolio, plus a Housing Fund administered by Treasury. Under its aegis, the New South Wales Government built a model suburb aligned with prevailing British ideals. Located beside Botany Bay, Dacey Garden Suburb boasted well-built, well-lit and well-ventilated houses, set in leafy streets amid churches, schools and shops.8 Daceyville’s 315 rental homes comprised what would later be termed ‘social housing’, while another Treasury sub-branch, the Resumed Properties Department, erected low-cost dwellings at Stockton, north of Newcastle.

Although these initiatives offered uplift for non-Indigenous residents, this was also an era in which the State’s First Nations communities were systematically excluded from citizenship, voting and many places that they yearned to live. Devastatingly, a 1915 amendment to the Aborigines Protection Act 1909 empowered the Aborigines Protection Board to separate children from their families.9 Neither an apology nor compensation for this profound injustice would be forthcoming until the 21st century.

War and repatriation

In January 1914, Premier William Holman also became Treasurer, a taxing double duty that he maintained until October 1918. These tumultuous years spanned World War I, during which Holman was expelled from Labor for championing conscription for overseas military service. He remained Premier and Treasurer, however, thanks to support from the new Nationalist Party led by Prime Minister William ‘Billy’ Hughes.10 The failure of two attempts to introduce conscription meant that Australia’s armed forces remained entirely voluntary throughout the conflict. The social contract thus cut both ways, with personnel enlisting for ‘King and country’ – rather than individual states – and expecting the nation to honour their service upon return.

Australia committed to supporting Britain even before war was declared on 5 August 1914.11 The NSW Government swiftly assured public servants that their jobs were secure if they enlisted. On 14 August, the Premier’s Office advised that staff who joined up would keep drawing their wages from NSW Treasury. Any military pay from the Australian or Imperial governments would instead be diverted into the State’s consolidated revenue. Two weeks later, Holman announced that ‘the New South Wales Government will be responsible for payment of the difference between military and State pay’.12 Both patriotic and generous, this subsidy was extended in 1917 to public servants travelling to Britain as munitions workers, then again in 1919 for personnel re-enlisting for post-war occupation duty in Germany.

Treasury also supported those returning from the conflict. While veterans of colonial wars in Sudan, South Africa or China already received limited State pensions, they were primarily cared for by families and charities.13 From 1914 a new range of organisations raised funds for returnees from World War I, including the Red Cross, the Australia Day Fund and the Association of Centres for Soldiers’ Wives and Mothers. But the vast scale of enlistment soon made it clear that ‘however prodigious their efforts, the patriotic associations could not cope with the scale of veterans’ needs, and the state would have to assume an unprecedented role’.14

Meanwhile, the burgeoning Returned Servicemen’s Association agitated for preferential benefits for former soldiers. They found a ready ear with Holman, who in July 1916 issued a bombastic manifesto, ‘The State’s Duty to the Soldier’. The accommodation, rehabilitation and compensation of injured veterans, he proclaimed, ‘should be lifted out of the domain of voluntary and spontaneous action and organised by the State itself’.15 He committed New South Wales to matching the proposed federal pension of 1 pound per week for totally incapacitated veterans, doubling their stipend to 2 pounds. The Housing Board would also ‘immediately commence to build a large number of houses in selected areas in Sydney, or in other districts where permanently disabled soldiers ask for them’, such as Tamworth.16 With breathtaking fiscal audacity, Holman admitted there was no budget for this lavish scheme, although it might cost Treasury up to 50,000 pounds per year – nearly 5 per cent of the State’s appropriation.

Yet such largesse came hot on the heels of diminishing government revenues. The naval supremacy of the Empire allowed Britain to ‘use the great oversea markets of the world’ to maintain its global war effort.17 While the resultant export boom benefited Australia’s primary producers, the pronounced decline in imports severely curtailed customs revenue, leading the Commonwealth to introduce income tax and estate duties in 1915.18 Conversely, the New South Wales Probate Duties War Exemption Act 1915 excluded duty on ‘the estate of any person who during the present war, or within one year after its termination, has died or may hereafter die… as a result of injury received or diseases contracted on active service’.19 Thus even as they introduced overlapping and contradictory tax laws, New South Wales and the Commonwealth continued to joust for the hearts and minds of the people.

Pensions remained a key battleground. When the Commonwealth passed the War Pensions Act in October 1914, the New South Wales Government had already enacted the National Relief Fund Act 1914. This legislation permitted the State to accept bequests, gifts or subscriptions, either investing them in government or commercial banks, or depositing them with the Treasury. Such monies were reserved for ‘the relief of persons injured in war or public disasters or those dependent on persons killed or injured in war or public disasters’.20 Despite their fine intentions, neither the State War Council nor the National Relief Board of New South Wales approached this herculean task efficaciously. Unsurprisingly, notes historian Philip Payton, ‘the public remained unconvinced by what appeared to be a hasty cobbling together of disparate activities and interests – Commonwealth, state and private – and there was little confidence that the fund would succeed’.21

Someone had to take command. A comprehensive Australian Soldiers’ Repatriation Act was passed by the Australian Parliament in September 1917, creating a new Commonwealth Department of Repatriation and governing Repatriation Commission. But once again, Premier Holman struck first. In August he announced that NSW ‘Public Officers who return from the war partially incapacitated and receive war pensions’ would be managed by a board whose operations were ‘undertaken by the Treasury’.22 Nevertheless, the administration of both war pensions and repatriation benefits ultimately passed to the Commonwealth. In this way, propose historians Stephen Garton and Peter Stanley, ‘Australia in effect created a second welfare state’, reducing reliance on community assistance while dividing the dependence of needy citizens between federal and state treasuries.23

The larger costs of war generated a massive fiscal drain and a matching burden of both direct and indirect taxes. ‘Each year of the war’, pointed out The Australian Encyclopaedia in 1927, was ‘marked by the introduction of a new form of federal taxation’.24 In 1913–14, the last full year before hostilities, the Commonwealth derived 16,587,906 pounds from taxes. By 1918–19 the sum nearly doubled to 32,864,486 pounds. State taxes meanwhile bloomed by 90.0 per cent, yet local rates rose by a mere 30.1 per cent. The net change for the average Australian was a 77.9 per cent rise in their annual taxation obligation, from 5 pounds 12 shilling and 6 pence in 1913–14 to 10 pounds 2 pence just five years later.25 Citizens were certainly sharing the cost of their government’s ‘coin o’ kindness’.

Armistice and pestilence

The Armistice of November 1918 did not end the contest to socially elevate the populace. With the Commonwealth introducing the War Service Homes Act 1918, Holman could proudly point to his 1916 promise of housing for the State’s heroes. New South Wales was also freeing up land for returned soldiers to commence a new life as farmers, albeit with the Commonwealth footing the bill. Meanwhile, any NSW resident who earned under 400 pounds per year was now eligible for a 30-year government home loan. Courtesy of Treasury’s Housing Fund, a mere 5 pound deposit secured house plans and specifications ‘in accordance with the applicant’s desires’.26

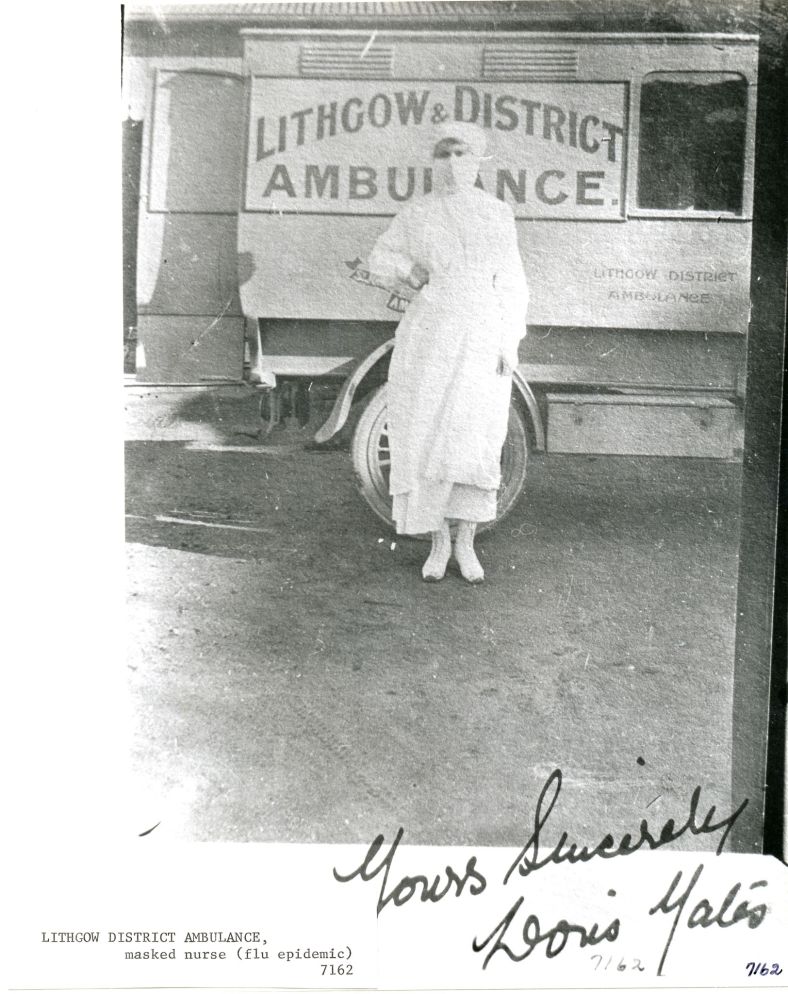

Another Treasury offshoot, the Insurance Board, introduced a Special Public Liability Insurance Scheme in 1919 that offered low-cost cover for hospitals, benevolent societies and the other community associations that prospered during the 1920s, from Rotary to Legacy.27 That July the Board also generously underwrote policies for nurses, hospital staff and voluntary aid workers ‘engaged in assisting to control the outbreak of pneumonic influenza’.28 Generating social anxieties not again witnessed until COVID-19 a century later, the ‘Spanish’ influenza pandemic caused well more than 50 million deaths worldwide, including more than 6,200 in New South Wales.29

The NSW Government soon imposed a drastic series of regulations to reduce the spread of infection. These included the closure of racecourses and billiard halls, theatres and music venues, hotels and wine bars, and both public and fee-paying schools. Although primarily targeting the greater Sydney region, restrictions also reached regional centres, from Albury to Armidale.30 ‘We should be grateful… to the Government for introducing such a vigorous prophylactic campaign’, proposed the Sydney University Medical Journal. ‘By such they have not only saved many citizens from infection but have slowed down the spread of disease’.31

But for many proprietors and landlords – and their employees and tenants – the results were ruinous. Within weeks of the first proclamations in late January 1919, thousands of citizens were laid off, from musicians to meatpackers. They soon sought succour from the 10,000 pound Distress Relief Fund announced by the new Treasurer, John Fitzpatrick, and administered via neighbourhood relief depots.32 These were typically established by local councils who doled out rent and sustenance payments on behalf of Treasury.33 While some shires and municipalities were unhappy with the State’s management of the crisis, other councils followed Parliament’s appeal to fund temporary works that kept residents employed.34

Where New South Wales really stood out was a proclamation issued by Governor Sir Walter Davidson on 27 February 1919. He considered it ‘just and right that inasmuch as the closing of such places of business and amusement has been for the public welfare the Government should assume responsibility for so much of such debts and obligations… as it may deem equitable’.35 The proposed terms included reimbursing one-third of rental or mortgage payments, half of the interest on loans or hire fees, and a proportion of other losses associated with enforced closures. In April a Pneumonic Influenza Claims Committee was established, including Treasury’s Sub-Accountant Andrew Lynch, which advanced payments to applicants in extreme situations.

In this way, New South Wales became the only Australian state to offer financial compensation for businesses and individuals who complied with pandemic regulations. The process was formalised via the Influenza Epidemic Relief Act 1919, passed in December with an appropriation of 68,961 pounds. It honoured Davidson’s decree by offering partial relief from rates and taxes – ‘not including Federal taxes’ – plus insurance premiums and ‘wages of any indispensable employee’.36 Notably, benefits were provided to residents from diverse immigrant backgrounds, including workers with Italian, French, Scandinavian, German and eastern European surnames. However, reflecting the nation’s fervent embrace of the ‘White Australia policy’, public money rarely aided those of Chinese or Japanese heritage.

Administration of the Influenza Epidemic Relief Act was overseen throughout 1920 by Royal Commissioner, William Kessell. He was regularly bemused and sometimes affronted when claimants supposed ‘that an opportunity presented itself to obtain a grant from the Public Exchequer without any vigilance being exercised as to their bona fides’.37 Kessell struggled with the propriety of reimbursing wages for private schools but not Catholic colleges, since their teaching brothers and sisters were not salaried. Conversely, he reprimanded publicans who claimed losses for closing their hotels without admitting that they profited handsomely from home-delivering alcohol, as permitted within influenza regulations. ‘Overloaded claims were the rule’, Kessell observed, ‘and no item relating to the business seemed to be too remote to be included.’38

Ultimately, 1,797 submissions amounting to 214,094 pounds were considered, with 827 receiving some compensation. Including the advances provided by the Claims Committee in 1919, the total cost to Treasury was 30,020 pounds – just 14 per cent of the total requested and less than half the reserved appropriation. Concluding his final report in December 1920, Kessell mused that his duties in monetising the social contract had ‘entailed much consideration and anxiety, particularly in view of the fact that, in a majority of cases, the interests of the State and of the individual were in conflict’.39

Stability and responsibility

If the 1910s represented a period of fiscal extremity and experiment, Treasury itself remained an extraordinarily stable instrument of government. The economic ambition of New South Wales’ new obligations was illustrated by the 89 per cent growth in the annual appropriation, from 13,701,181 pounds in 1911 to 25,895,593 pounds in 1920. Over the same period, seven men were appointed Treasurer, three subsequently becoming Premier. In contrast, Treasury was overseen by just one permanent head: lifelong public servant John Holliman served as Under Secretary for Finance and Trade from 1907 until retiring in 1922.40

The cost of this stability, however, was administrative stasis. Over 1911–1920, Treasury’s own appropriation rose by just 15 per cent, from 28,048 pounds to 32,162 pounds.41 A correspondingly modest rise in staffing, from 108 to 120 personnel, meant that officers were hard-pressed to maintain the State’s basic book-keeping. Senior administrators were rarely available – or willing – to advise the Treasurer on higher-order economic decisions. The primary cause was World War I, which halted hiring of new staff and curtailed salary increases. Enlistment also generated significant staff turnover. No fewer than 15 personnel joined Treasury’s Honour Roll, including 18-year-old clerk Clarence Pollard, killed at the Battle of Flers in November 1916.42 While the absence of young men created a few opportunities for women, employment preferences firmly remained with returned servicemen.

If chivalric sentiment expired on the battlefields of Europe and the Levant, its last gasps benefited many citizens across New South Wales. By 1920, Treasury could finally afford advances in office technology such as calculating and bookkeeping machines, although more wide-ranging procedural reform remained years away.43 Indeed, 1920 also witnessed the nation’s first Royal Commission into taxation, which aimed to reduce administrative overlaps and revenue conflicts between Commonwealth and state systems.44 But a deeper transformation had already occurred in the mutual relationship between citizen and state, especially the central role of NSW Treasury in funding the new social contract.