Women’s workforce participation

Over the past 40 years, the number of women in the NSW workforce has increased significantly, rising from 51 per cent of working-age women (aged 15–64) in 1981 to 74 per cent in 202113.

51% proportion of women aged 15-64 participating in the NSW workforce in 1981

74% proportion of women aged 15-64 participating in the NSW workforce in 2021

This increase is attributable to significant improvements in women’s access to education, policies to address gender discrimination, improved access to paid parental leave and childcare, society’s evolving attitudes, strong growth in services industries that have traditionally employed a greater share of women, and the greater availability of part-time and flexible work.

Women’s participation remains lower than men’s

Despite this increase, women’s workforce participation continues to lag well behind that of men. In 2021, working-age women in New South Wales (aged 15–64) had a labour force participation rate of 74 per cent, compared to 82 per cent for men14.

This equates to about 210,000 fewer working-age women in the workforce than if they participated at the same rate as men.

Under current policy settings, the participation rate for working-age women is projected to increase only slightly to 76 per cent by 2061, compared to the projection of 83 per cent participation by working-age men15.

Figure 1: Actual and projected NSW participation rates for men and women aged 15-64 under current policy settings

Women’s participation starts to lag behind men’s from their late twenties

While the number of men and women joining the workforce in their late teenage years and early twenties is similar, women’s participation rates drop below men’s from their late twenties.

As shown in Figure 2, female participation rates stabilise at about 80 per cent between the ages of 25 and 54 years, while male participation rates continue to climb to more than 90 per cent and remain high until retirement.

Figure 2: Workforce participation rates for NSW men and women by age in 2019

Women are more likely to work fewer hours than men

Women who are employed are more likely to work in part-time or casual roles. In 2021, 39.4 per cent of employed women in New South Wales were working part-time compared to 18.2 per cent of men16.

In the same time period, 22.6 per cent of women employed in New South Wales were in casual work, compared to 19.3 per cent of men17.

The rates of part-time work also change according to age.

Figure 3 shows that the proportion of women working part-time increases by 15 percentage points between the age ranges of 25–29 years and 35–39 years, whereas the percentage of men working part-time falls 11 percentage points over the same period.

Figure 3: Proportion of NSW women and men in part-time and full-time work

Women are also more likely to be underemployed

This term refers to people who are employed full-time but have worked part-time hours for economic reasons (such as being stood down, or because there was insufficient work available), as well as people who are available and would prefer to work more hours18.

In 2019, 10.2 per cent of women in the labour force of New South Wales were underemployed, compared to 6.5 per cent of men19.

Figure 4: Main reason Australians who wanted to work or take on more hours were unable to start a job or work more hours in FY2018-19

Caring for children is a key reason why women work less

As shown in Figure 4, the main reason Australian women want to work or take on more hours but are not available to start is because they are caring for children.

Caring for children is far more likely to impact women’s employment opportunities than men’s.

Almost half of Australian women (47.9 per cent) who are willing to work or take on more hours report that caring for children is the main reason they are unable to start a job or work more hours, compared to 3.2 per cent of men.

The longer women remain out of the workforce, the less likely they are to return to work

When women spend longer periods of time out of the workforce to care for children, they are less likely to return to work.

With each year a woman spends out of the workforce, their professional skills, knowledge and networks can fall further behind the latest standards.

This means that women returning to the workforce after a long break face a greater barrier in updating their skills than women that take a shorter break.

Women are also more likely to lack confidence in their abilities after lengthy periods without paid employment.

One study found the probability of women not returning to work after a short period away for non-child-related reasons is 10 per cent, while the probability of women who take longer, child-related career breaks never returning to the workforce is 30 per cent20.

Caring responsibilities are not evenly split between parents

On average, women continue to perform a far larger share of caring work at home than men. Consequently, women take more time out of the workforce to manage competing responsibilities21.

This is reflected in the average time-use of mothers and fathers before and after having children as set out in Figure 5.

The amount of time spent by fathers in employment remains virtually unchanged after having a child, whereas mothers’ time-use patterns change significantly.

Conversely, after having a child, the number of hours mothers spend on childcare increases dramatically.

Mothers have low levels of employment when their youngest child is less than one year of age, and while this does increase over time, it does not recover to the level before they had children22.

Figure 5: Average time-use of parents before and after having children

For many parents, early childhood education and care remains expensive and hard to find

Subsidised childcare was introduced in the 1970s by the Commonwealth Government and has played a significant role in supporting parents to return to work after having children.

Over the past 50 years, the subsidy has steadily increased, alongside increases in female workforce participation.

Currently, the Commonwealth Government provides a subsidy to providers to help reduce fees for parents. This subsidy currently covers up to 85 per cent for the first child and up to 95 per cent for other children, with the amount tapering off as household income rises to $354,305.

Despite the current subsidy levels, some women face very difficult decisions regarding whether to return to work or to continue to care for their children at home.

Figure 6 below sets out the workforce disincentive rate, which is an indicator of the amount of take-home pay a parent receives for each additional day of work after income tax, the withdrawal of family tax benefits, and costs.

Workforce disincentive rates vary depending on mothers’ incomes. For a family with a combined income of $120,000 a year with two children, where the father earns $70,000 and the mother earns $50,000, the mother only takes home around 25 cents of each additional dollar earned when she works more than one day a week.

Figure 6: Workforce disincentive rates faced by secondary income earners with two children at current Child Care Subsidy levels

This analysis shows how the cost of early childhood education and care, combined with income tax and withdrawn family benefits, erodes mothers’ earnings and removes much of the financial incentive to return to the workforce.

The newly elected Commonwealth Government has announced its intention to lower the cost of childcare for households, primarily through increasing the Child Care Subsidy to up to 90 per cent for the first child, with the subsidy tapering as household income rises and reaching zero for households with incomes over $530,00023.

Though this reform will lower the cost of childcare for many families, Figure 7 shows that many families will still face high workforce disincentive rates under the proposed Commonwealth Government arrangements.

For the same family described above with a combined income of $120,000 and two children, they will take home between 32 and 34 cents for each additional dollar earned when she works more than one day.

Figure 7: Workforce disincentive rates of secondary income earners with two children at different incomes at Child Care Subsidy levels proposed by the incoming Commonwealth Government

Another challenge parents face when seeking to enrol their child in childcare is accessibility. This is because of a number of barriers that prevent increased demand-side childcare subsidies from stimulating the delivery of increased supply. These include:

Workforce shortages: there are entrenched and worsening shortages of early childhood teachers and educators across Australia, including in New South Wales. These shortages have been significantly exacerbated by COVID-19, but even before the pandemic, staff turnover rates were as high as 30 per cent and it was predicted that 39,000 additional educators would be needed nationally by 202324 25. For New South Wales, this equates to as many as 10,500 educators and 3,150 degree-qualified early childhood teachers.

During the COVID-19 pandemic, the workforce, as frontline staff, were hard hit with many peak organisations and employers reporting staff leaving the sector. Anecdotal evidence as of May 2022 is suggesting services continue to close rooms due to staffing shortages – meaning fewer children can attend on a given day.Thin markets: many communities across New South Wales, particularly in regional areas, do not have a sufficiently deep childcare market to stimulate competition amongst providers. Because there is a higher marginal cost in providing education and care on a small scale, many providers will not enter rural markets even if there is unmet demand.

Information asymmetry: childcare providers often face a lack of transparency surrounding the level of demand in local markets. Detailed knowledge of a community’s needs can be difficult to develop, and there is a shortage of quality formal data on the appetite for childcare in different geographical areas. This means it is difficult for supply to be marshalled to meet demand26.

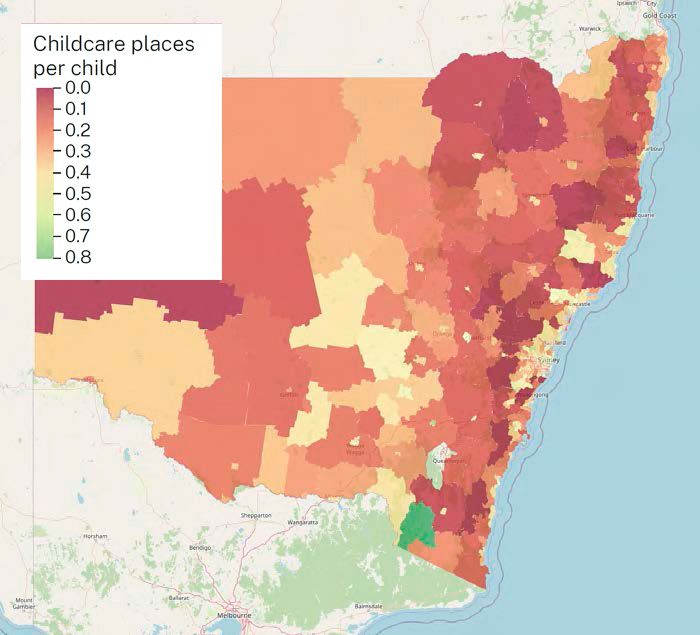

The Mitchell Institute research shows that the current system has resulted in many places being offered in areas where families can pay higher fees, and a relative scarcity of places in lower socio-economic parts of New South Wales, particularly in regional New South Wales, south-west Sydney and Western Sydney.

The Mitchell Institute found that 35.2 per cent of the Australian population live in ‘childcare deserts’, which refer to populated areas with less than 0.33 childcare places per child (excluding community preschools and family day care providers)27.

Research of Australian, US and the Netherlands demand-side support systems also suggest that demand side subsidies also result in supply shifting to higher income areas, and away from regional areas and areas with underserved communities28.

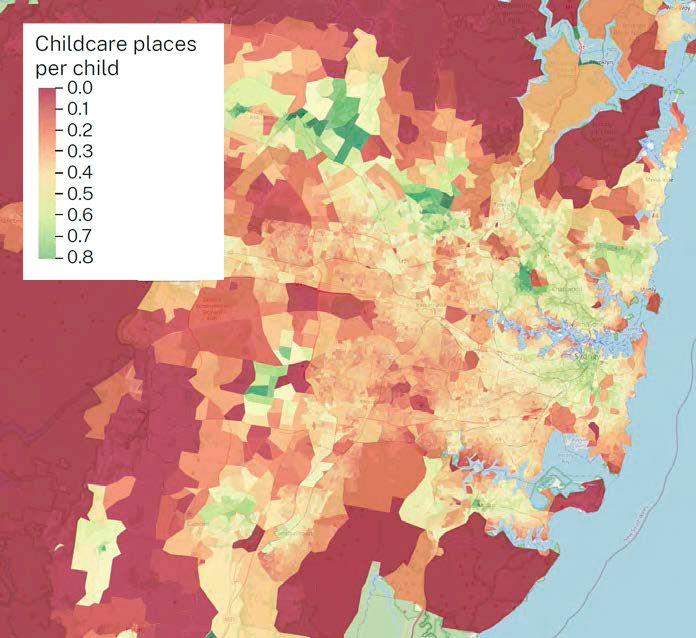

While the Mitchell Institute maps do not include family day care or community preschool, Figures 8 and 9 illustrate the relative childcare accessibility issues faced by parents living in parts of New South Wales.

These issues are highly complex. The childcare sector comprises private, not-for-profit and government providers, and is characterised by significant disparities in pricing, accessibility and quality.

In addition, the Commonwealth and NSW Governments have overlapping roles and responsibilities.

The result of these points is fragmentation in most areas of the sector, such as Commonwealth subsidies and lack of transparent data impeding good decision-making and planning.

The NSW Government has the opportunity to further support improvements in the provision of high quality and accessible childcare.

| Figure 8: 'childcare deserts' in Greater Sydney | Figure 9: 'childcare deserts' in NSW |

|---|---|

|  |

Source: Mitchell Institute, Victoria University, Deserts and oases: How accessible is childcare in Australia?

Unequal sharing of paid parental leave contributes to the participation gap

Paid parental leave is an important part of supporting parents in the workforce.

The first national paid parental leave scheme was introduced in 2011 under the Paid Parental Leave Act 2010 (Cth). Under the national scheme and following recent announcements by the Commonwealth Government, by March 2023 eligible families across the country will be able to access up to 20 weeks’ leave paid at the minimum wage, which can be shared between parents.

Many major employers across Australia, including the NSW Government, provide parental leave at full pay.

Introducing paid parental leave has supported many women to keep a connection to their workforce while taking important time to spend with their newborn children.

This is reflected in the strong uptake of the Commonwealth Government’s paid parental leave by mothers, shown in Figure 10.

Uptake of paid parental leave by fathers, however, has remained low. Indeed, when the Commonwealth Government’s paid parental leave scheme was reviewed in 2014, more than 99 per cent of all primary carers were women29.

For every 10 women claiming primary paid parental leave, only four men claim Dad and Partner Pay, which under the existing scheme is two weeks at minimum wage30.

Figure 10: Take up rates of the Commonwealth Government’s paid parental leave scheme (2011–2022)

The rates of fathers using parental leave in Australia are extremely low compared to global standards.

Male parents are far more likely to be secondary carers and to take a much shorter period away from work.31

Figure 11: Comparison of take up rates of paid parental leave by fathers

Women are more likely to care for elderly parents and other vulnerable members of the community

There are 854,300 carers in New South Wales32. A carer is anyone who provides ongoing unpaid support to people who need it because of their disability, chronic illness, mental illness or frail age33. Carers reduce the need for formal care and supplement the care provided by government services, thereby making significant social and economic contributions34.

Women are more likely to be carers than men, comprising 57.9 per cent of carers in New South Wales35 36.

This is even more significant for women in the midst of their careers, where women aged 45-54 accounted for almost three times the number of male primary carers across Australia37.

Both the Commonwealth and state and territory governments have responsibilities in relation to carers. The Commonwealth Government provides payments to eligible carers, including the Carer Payment and Carer Allowance. The NSW Government has a responsibility to carers in New South Wales through the Carers (Recognition) Act 2010, which recognises the right of carers to participate in economic, social and community life, that they should be supported to achieve greater economic wellbeing and sustainability and, where appropriate, should have opportunities to participate in employment and education38.

However, there is evidence that being a carer limits women’s opportunities to participate in the paid workforce, with many carers leaving paid employment or reducing their working hours to balance their caring responsibilities39 40.

Carers are less likely to be employed than non-carers, with 66.6 per cent of carers employed in 2018 compared to 77.4 per cent of non-carers41.

Primary carers who provide more hours of care per week are less likely to be employed. In 2018, 52.8 per cent of primary carers who provided fewer than 20 hours of care per week were employed, compared to 28.6 per cent of primary carers who provided more than 40 hours of care42..

Of the primary carers not in workforce, 25 per cent have indicated they would like to be employed, with the majority (85.7 per cent) wanting to work part-time43.

Carers also commonly face financial difficulties44. In 2018, the median weekly income of primary carers was $621, compared to $997 for non-carers, making it harder for carers to pay for living expenses, save money or build superannuation45. Carers also often have low levels of physical and mental health and wellbeing, and they struggle to balance paid work and their caring responsibilities46.

Not all women have equal access to flexible working arrangements, which may limit some women’s economic participation

While flexible working arrangements can benefit all employees, such arrangements are a particularly important enabler of women’s workforce participation. Access to flexible working can allow workers to remain in or re-enter the workforce while balancing their personal commitments, such as caring responsibilities.

Under the Fair Work Act 2009 (Cth), many employees have a right to request flexible working arrangements. Employees are entitled to make a flexible working request if they have worked for the same employer for at least 12 months and are a parent of young or school-aged children, a carer, a person with a disability, aged 55 or older, or experiencing family violence47.

However, there have been challenges in translating this right to request flexible work from policy to practice48. Employees who do not meet the criteria outlined above are not entitled to request flexible working arrangements under the National Employment Standards. Furthermore, employers may refuse flexible working requests on reasonable business grounds49.

Reasonable grounds include if the requested arrangements would be too expensive, it would be impractical to change other employees’ working arrangements or to recruit new staff to accommodate the request, or if it would have a significant detrimental impact on customer service.

The inability to access flexible working arrangements can be an impediment to both workforce participation and career progression for women, particularly in certain sectors. Women who have difficulty accessing suitable flexible work opportunities in their chosen field may end up accepting jobs below their skill level or in another field that are lower paid and less secure, thereby inhibiting their career development50.

Download or print

Request an accessible format of this publication.