Download or print

Request accessible format of this publication.

Women have many different health needs and experiences to men, in particular those associated with fertility and sexual health which occur throughout a woman’s working life.

Women’s health outcomes have improved dramatically over recent decades thanks to medical advances, public health provision and major health awareness campaigns.

Life expectancy for women has risen from 84 years in 2006 to 85.2 years in 2016. More than 83 per cent of girls aged over 15 years are fully immunised against human papillomavirus.

However, many challenges remain.

This section sets out some of those challenges which particularly affect women’s ability to participate in the workforce and maintain the right to choose to have a family, a career or both.

Currently, one in six families will experience fertility issues throughout their lifetimes.

The University of New South Wales found that assisted reproductive technologies have become increasingly common among Australian families, with more than 81,000 treatment cycles in 2019 alone.

This is an increase of about 6 per cent on the previous year106.

This means that an increasing number of children are born in Australia because of assisted reproductive technologies, representing more than 18,300 of the almost 306,000 babies born in 2019.

Figure 20 shows how birth rates without assisted reproductive technology (ART) has declined by almost 4 per cent over the past 20 years in Australia, with a corresponding increase in the number of births from assisted reproductive technologies.

Despite medical advances, IVF treatment and fertility preservation can be emotionally and financially difficult for women and their partners108.

While Medicare covers some related costs, the financial burden of IVF treatment and fertility preservation is often prohibitive for some women, preventing them from accessing services which would give them the best chance of conceiving.

The estimated out-of-pocket cost is up to $5,500 for an IVF cycle and up to $2,400 for a frozen embryo transfer cycle.

Some women require subsequent cycles which may be provided at a slightly lower cost if undertaken in the same year. These costs may differ depending on individual circumstances, insurance cover and the service that is used.

Costs also remain high for fertility preservation treatments, with egg-freezing costs sitting around $4,500 for the first cycle and $4,000 for subsequent cycles. Ongoing storage is around $50 per month and medications from $1,500 per cycle.

The reproductive health needs of women can often result in women having to take time off work, not just in the postnatal period.

For example, women who undergo assisted reproduction treatments may require time off work to rest after the procedures.

Equally, women who experience a miscarriage may also require a period away from the workplace to rest and recover.

Under the Fair Work Act 2009 (Cth), women generally have to rely on their personal or annual leave for periods away from work relating to fertility and reproductive health.

While compassionate leave provisions have been extended for some of these reasons, there remains gaps in entitlements.

Some larger employers are now offering paid leave to employees undergoing IVF treatments, as well as leave for miscarriage and pre-term births109 110.

Some women develop mental health conditions (such as postnatal anxiety or depression) after having a baby and adjusting to motherhood.

Some women may be at particularly high risk, including women with a personal or family history of mental health conditions and who lack social or emotional support and have increased life stresses.

Mental health disorders can affect women at any time in their life, but there is an increased chance of mental ill-health during pregnancy and the year following the birth.

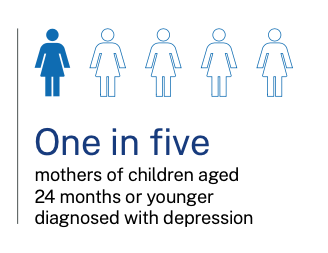

Data from the 2010 Australian National Infant Feeding Survey showed that in 2010–11, one in five mothers of children aged 24 months or younger had been diagnosed with depression, and more than half of these mothers reported that the depression was diagnosed from pregnancy until the child’s first birthday111.

The increased life stresses caused by COVID-19, including uncertainty, financial stress and social isolation, have led to increased demand for postnatal mental health support.

Accessing mental health support early is important for the wellbeing of both mothers and their children.

Women may experience a range of symptoms during menopause. It is estimated around 85 per cent of women will experience at least one symptom of menopause, which can include hot flushes, night sweats, sleep disturbances, sexual dysfunction, mood disorders, weight gain and cognitive decline112.

While some women may only experience mild symptoms during menopause, around 20 per cent of women experience more severe or prolonged symptoms which may significantly affect their quality of life and impact on their ability to work113.

In addition to the common side effects, menopausal women also face increased risk of osteoporosis and declining bone health, cardiovascular disease and stroke, weight gain, urinary continence problems, and heavy or uncontrolled bleeding.

When women experience menopausal symptoms, it impacts on their ability to enjoy a fulfilling social life or pursue activities that enhance their financial security.

Women suffering from ill health are also less likely to seek a promotion or actively engage with their work, and more likely to take extended leave or leave their job114.

Research indicates that women may not want to draw attention to the health impacts of their perimenopause or menopause. A social taboo exists around menopause that makes it less likely women will discuss their symptoms or seek professional medical assistance.

There are a range of treatments available to manage symptoms of menopause, including eating well, regular physical activity, menopausal hormone therapy, non-hormonal prescription medications and complementary therapies.

Beyond direct medical treatment of symptoms, it is also essential to break down social stigmas around discussing menopause and seeking treatment.

It is vital to foster recognition that menopause can have profound effects on women’s health and wellbeing and, by extension, significant impacts on their social and economic lives.

While some progress has been made towards closing the gap, there continue to be significant disparities between the health and educational outcomes of First Nations children and adults compared to the non-Indigenous population.

For example, First Nations people have lower life expectancies and higher suicide rates115.

First Nations children have lower rates of participation in preschool, and only 35.2 per cent of First Nations children are assessed as developmentally on track in all five domains of the Australian Early Development Census, compared to 56.6 per cent of non-Indigenous children116.

This suggests that existing services for the general population are not meeting the needs of many First Nations women and their families, and that tailored approaches to service delivery are required.

Research suggests that integrated, holistic and culturally safe services may better meet the needs of First Nations women and their families; for example, co-locating multiple services such as early childhood education and care, parent and family support, maternal and child health, and adult education opportunities.

“For First Nations women, economic prosperity starts with strength in culture. If we don’t have culture, we don’t have anything. Culture is family, it’s connection to country and community.”

Consultation participant, Expert Reference Panel (March 2022)

Although having the ability to participate in sport is a critical part of maintaining women’s physical and mental health, women have lower levels of participation on average compared to men.

Rates and patterns of participation in sport not only differ between genders, but also fluctuate over the life course117.

Only 21 per cent of girls in New South Wales aged 0–14 play an organised sport and physical activity outside school hours three times a week, and their rates plateau when they reach adolescence118.

By contrast, boys participate in organised sport and physical activity at consistently higher rates, and their participation increases with age119.

Evidence also shows girls and women from disadvantaged areas have lower rates of participation compared to those in more advantaged areas120.

The NSW Government has made significant investments to upgrade sporting facilities across the State to include female change rooms and safer lighting. However, there is further demand for upgrades, with many community sporting grounds still lacking the infrastructure needed to support women’s participation in sports.

Request accessible format of this publication.